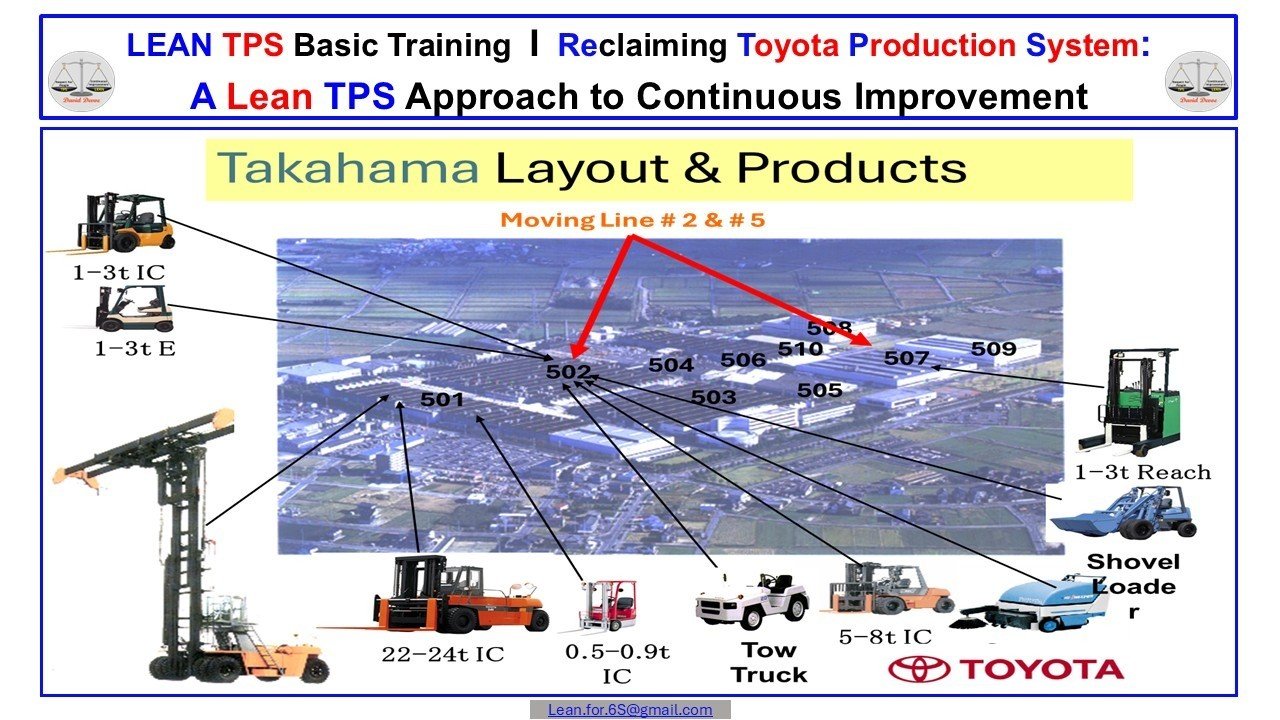

Toyota L&F Takahama stands as one of the clearest demonstrations of how the Toyota Production System becomes a living structure when applied with precision and discipline. Established in 1970 and operated under Toyota Industries Corporation, the plant produces a full range of material handling equipment including electric and internal combustion forklifts, tow tractors, and shovel loaders. Spanning 500,000 square meters with 222,000 under roof, Takahama operates as a model of small-lot, high-mix production at global scale.

When I trained there, I saw that TPS was not taught through slides or lectures. It was lived through daily practice. Every building, every moving line, and every layout decision reflected purpose. The map of Takahama shows how flow is designed. Each hall, numbered 501 to 510, connects through internal logistics that allow mixed-model production to move without interruption. Lines 2 and 5, shown in red, demonstrate this connection in real time. Forklifts, reach trucks, and tow tractors move through linked systems of fabrication, welding, painting, assembly, and inspection. What looked like separate shops revealed themselves as one continuous flow of value.

The most striking feature of Takahama was rhythm. Production followed a steady takt that governed the movement of materials and people. This rhythm was not enforced by management; it was sustained by structure. Visual controls, andon systems, and standardized work defined what normal looked like. When abnormality occurred, leaders responded instantly. The design of support was embedded into the layout itself. Each team leader had direct line of sight to their operators, and assistance could be given without delay. That support system allowed improvement to occur naturally because problems were seen early and corrected quickly.

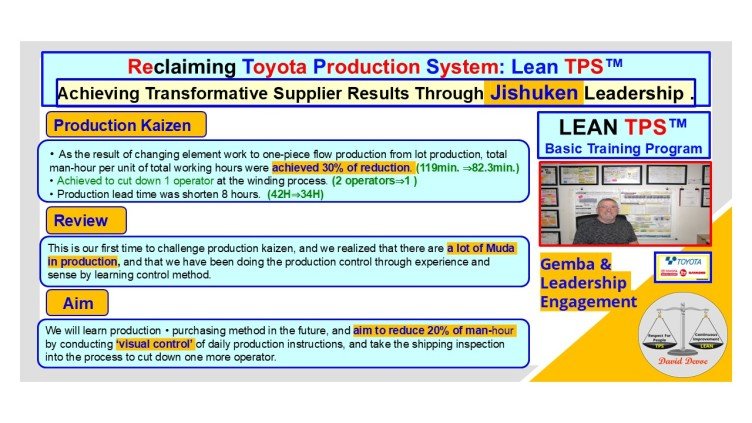

Training at Takahama was total immersion. In machining, I learned how one operator could manage multiple machines through standardized sequencing. In welding, I observed jigs that prevented defects by design. In painting, I saw how even small surface inconsistencies were logged and traced. In assembly, I measured work balance and sequence through Standardized Work Combination Tables. Every process was defined, measured, and visualized. Each step supported the next.

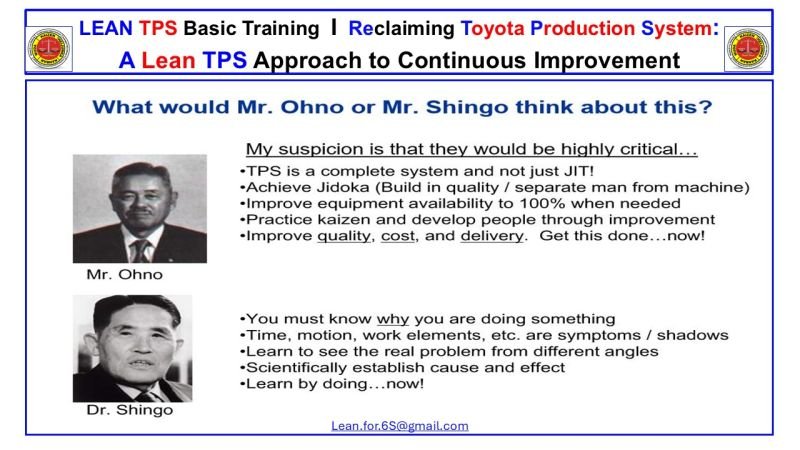

The most important lesson came from watching leadership. Team Leaders and Assistant Team Leaders were not inspectors. They were coaches. Their work was to confirm standards, develop people, and teach problem-solving. They stood at the Gemba, asked questions, and recorded facts. When problems appeared, they guided operators to investigate the cause and design countermeasures using A3 and PDCA thinking.

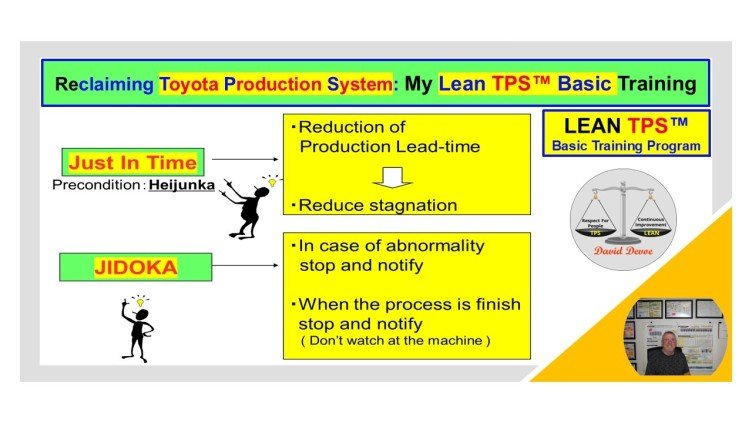

By the end of my training, I saw how Takahama connected all functions into one system. Production, logistics, maintenance, and quality worked together in a continuous cycle of learning. Kanban, Heijunka, and Jidoka were not separate tools. They were the foundation of a culture where every person contributed to stability and improvement.

Takahama showed that the Toyota Production System is more than manufacturing excellence. It is an organizational philosophy that aligns structure, people, and purpose. Its strength lies not in technology, but in the discipline of seeing and responding. Every improvement, every layout, every cycle is designed to make learning visible and sustainable.