Jishuken as Leadership Governance in Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid Environments

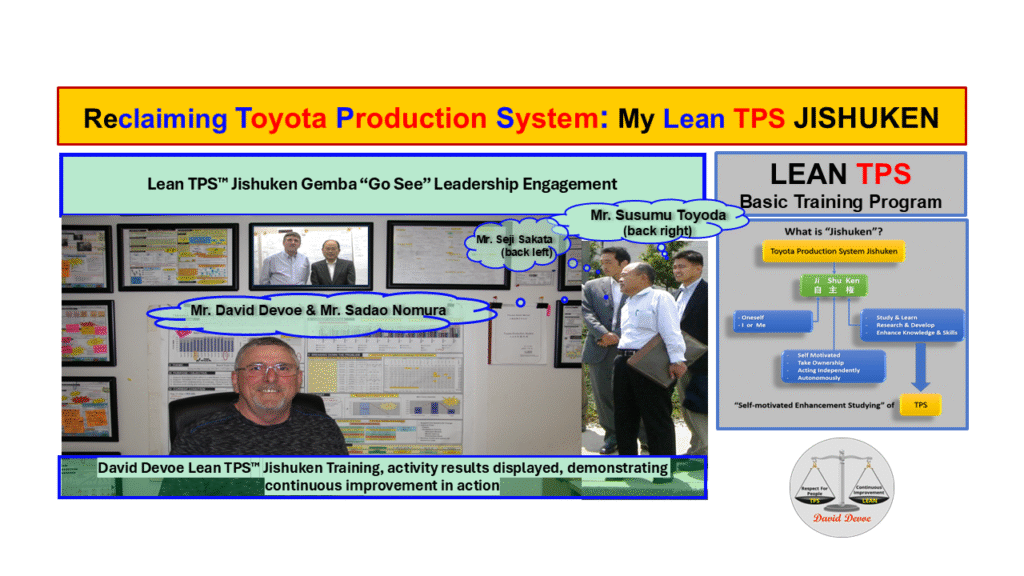

1. Developing Leaders Who Define, Verify, and Govern Normal at the Gemba

Figure 1 – Inspiring Leaders to Drive Jishuken: Leaders develop capability through direct participation in structured study at the Gemba.

Introduction

In Lean TPS, Jishuken exists to develop leaders who can govern complex systems under real operating conditions. It is not a Kaizen event, not operator training, and not a problem-solving workshop. Jishuken is the disciplined mechanism through which leadership learns to define normal, expose abnormality, and stabilize execution across people, processes, and technology.

As organizations enter Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, leadership responsibility increases. Execution is no longer buffered by informal human judgment or silent compensation. Quality risk rises when work intent, sequence, and escalation logic are not explicitly defined and governed. Jishuken prepares leaders for this reality by requiring direct engagement with facts at the Gemba and by holding leadership accountable for system behavior, not outcomes alone.

Why this matters for leadership

This image represents Jishuken as a leadership environment, not a training space. Visual strategy, study boards, and system models exist to make leadership thinking visible and testable. Jishuken places leaders inside the system they are responsible for governing. Observation, verification, and reflection are not delegated. They are owned by leadership.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, that ownership becomes nonnegotiable. Humanoids execute exactly what is defined. They surface abnormality without hesitation or interpretation. When leadership has not clearly defined normal conditions, escalation thresholds, and stop logic, Quality defects multiply rapidly. Jishuken exposes these gaps before they become systemic failure.

Jishuken develops leaders by removing distance between decision making and system reality. Leaders are required to stand at the point of work, compare actual conditions to defined standards, and confirm whether the system is behaving as intended. This is not observation for awareness. It is observation for governance.

The purpose of Jishuken is to teach leaders how to see. Seeing in Lean TPS means distinguishing normal from abnormal based on facts, not assumptions. It means understanding how flow, timing, sequence, and workload interact to either protect or erode Quality. It also means accepting responsibility when the system allows defects to pass undetected.

Jishuken is the primary method for preparing leadership to govern execution shared between humans and machines. Humanoids function as high fidelity Andon signals. They do not adapt, compensate, or reinterpret intent. When abnormalities occur, they are surfaced immediately. Leadership must decide what constitutes abnormal, when work must stop, and who owns the response. Jishuken is where those decisions are tested against reality.

This section establishes Jishuken as a leadership governance discipline. It defines the expectation that leaders, not systems or technology, are accountable for Quality outcomes. Jishuken does not reduce leadership burden. It clarifies it. By making system behavior visible and forcing verification at the Gemba, Jishuken prepares leaders to stabilize execution and protect Quality in environments where ambiguity can no longer be absorbed by human judgment.

2: The Lean TPS Global Jishuken Structure as Leadership Governance

How Leadership Responsibility Scales from Local Execution to Global System Integrity

Lean TPS organizes Jishuken as a leadership governance system, not as a training ladder or maturity model. The Global Jishuken structure defines how leadership responsibility scales from local execution to enterprise-wide alignment while preserving Quality, stability, and system integrity. Each level exists to expose system behavior, clarify ownership, and confirm that standards are holding under real operating conditions.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, this structure becomes critical. As execution is shared between humans and humanoids, leadership can no longer rely on informal coordination or local workarounds. Governance must be explicit, repeatable, and verified. The Global Jishuken structure provides the mechanism for that verification across organizational boundaries.

Figure 2: The Lean TPS Global Jishuken Structure: Leadership governance scales from local system control to global alignment through structured Jishuken activity.

Why this matters for leadership

At the base of the structure, Spot Kaizen and Quality Circle activity function as system sensors. Their role is to surface abnormality at the point of work and confirm whether defined standards are being followed. This activity is not about generating ideas or reducing cost. It exists to protect Quality by making deviation visible and requiring response.

Departmental Jishuken governs interfaces between functions. When processes cross departmental boundaries, ambiguity increases and accountability weakens. Departmental Jishuken forces leaders to study these connections directly, verify flow, timing, and workload balance, and resolve gaps that cannot be corrected within a single area. Responsibility shifts from local optimization to system stability.

Plant-Wide Jishuken addresses system behavior that affects the entire operation. Topics such as material flow, equipment reliability, staffing models, and leader standard work are examined as integrated conditions. Senior leadership participates directly to confirm that standards are aligned, escalation thresholds are clear, and response ownership is understood. This level ensures that instability is not managed informally or deferred.

Global Jishuken governs consistency across sites. As organizations scale, variation in interpretation and execution becomes a major Quality risk. Global Jishuken exposes differences in standards, decision logic, and response behavior. Leadership confirms what must be common, what can remain local, and how learning is shared without creating drift. This is not benchmarking for performance comparison. It is governance for system integrity.

The upward relationship between levels is not a progression of capability but a reinforcement of responsibility. Issues that cannot be resolved at one level are deliberately escalated to the next. Each level exists to absorb complexity that exceeds local authority while preserving clarity of ownership.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, this structure prevents silent failure. Humanoids surface abnormality relentlessly. When escalation paths are unclear or leadership response is inconsistent, Quality deteriorates rapidly. The Global Jishuken structure ensures that detection, escalation, and response remain aligned as system complexity increases.

This section establishes the Lean TPS Global Jishuken Structure as a leadership governance framework. It defines how responsibility scales, how learning is verified, and how Quality is protected across the enterprise when execution can no longer rely on human adaptation alone.

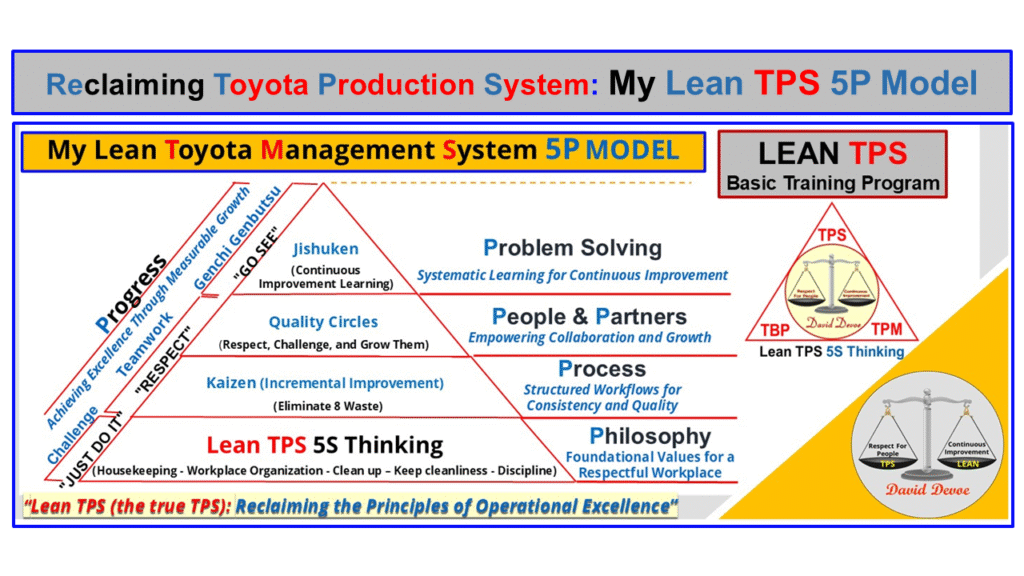

3: The Lean TPS 5P Model as a Leadership System for Governance

How the 5P Model Structures Leadership Accountability and System Governance

The Lean TPS 5P Model explains how leadership learning, system stability, and Quality governance are integrated into a single operating system. It defines how leaders are expected to think, act, and verify system behavior under real operating conditions. Within Jishuken, the 5P Model is not conceptual. It is the structure that governs how leadership responsibility is exercised at the Gemba.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, leadership can no longer rely on informal judgment, experience-based compensation, or personal intervention to stabilize execution. System behavior must be intentionally designed, verified, and governed. The Lean TPS 5P Model provides the framework that allows Jishuken to develop leaders capable of governing execution shared between humans and humanoids while protecting Quality.

Figure 3: The Lean TPS 5P Model: The leadership system that connects Jishuken learning to stable execution through philosophy, process, people, problem solving, and progress.

The 5P Model as the Operating Logic of Jishuken Governance

This model defines how leadership accountability is structured and sustained. It ensures that learning is anchored in purpose, executed through stable processes, reinforced through people, verified through problem solving, and confirmed through measurable progress. Without this structure, Jishuken becomes fragmented and leadership judgment becomes inconsistent.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, the 5P Model prevents governance gaps. Humanoids execute exactly as defined and surface abnormality immediately. When leadership philosophy is unclear, processes are unstable, or problem solving is inconsistent, Quality risk escalates rapidly. The 5P Model ensures that leadership decisions are aligned, repeatable, and testable against system behavior.

Philosophy establishes the purpose that governs leadership behavior. In Lean TPS, philosophy is not abstract belief. It defines responsibility for Quality, Respect for People, and long-term system stability. Leaders are accountable for ensuring that improvement activity develops people and strengthens the system rather than optimizing short-term results. In Jishuken, philosophy determines what leaders study, how they interpret abnormalities, and which responses are acceptable.

Process provides the conditions required for learning and governance. Stable processes define normal execution so abnormality can be detected. In Jishuken, leaders study actual work to verify flow, timing, sequence, and workload. Standardized Work and visual controls are not tools. They are governance mechanisms that allow leaders to confirm whether the system is behaving as intended. When process stability is lost, leadership responsibility is to restore it before further improvement proceeds.

People and Partners represent the human system that sustains learning. Leadership development in Lean TPS is not individual achievement. It is the ability to develop others who can see, think, and act based on facts. Jishuken builds this capability by requiring cross-functional participation and shared accountability. In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, this dimension ensures that humans retain ownership of judgment, escalation, and decision making even as execution is shared with machines.

Problem Solving is the discipline through which learning is verified. In Jishuken, leaders do not solve problems to achieve outcomes alone. They solve problems to understand system behavior. Structured problem solving confirms root causes, tests countermeasures, and validates results against standards. This discipline is critical when humanoids surface abnormality continuously. Leadership must determine whether abnormalities indicate local deviation or systemic failure.

Progress confirms whether leadership learning is effective. Progress is not measured only through performance metrics. It is confirmed through improved stability, clearer standards, faster detection, and more consistent response. In Lean TPS, progress indicates readiness for greater responsibility rather than completion. Jishuken uses progress to determine whether leadership capability has matured enough to govern more complex systems.

The Lean TPS 5P Model ensures that Jishuken functions as a leadership governance system rather than a collection of improvement activities. It connects purpose to execution, learning to responsibility, and detection to response. In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, this integration is essential to protect Quality when human adaptation can no longer absorb system ambiguity.

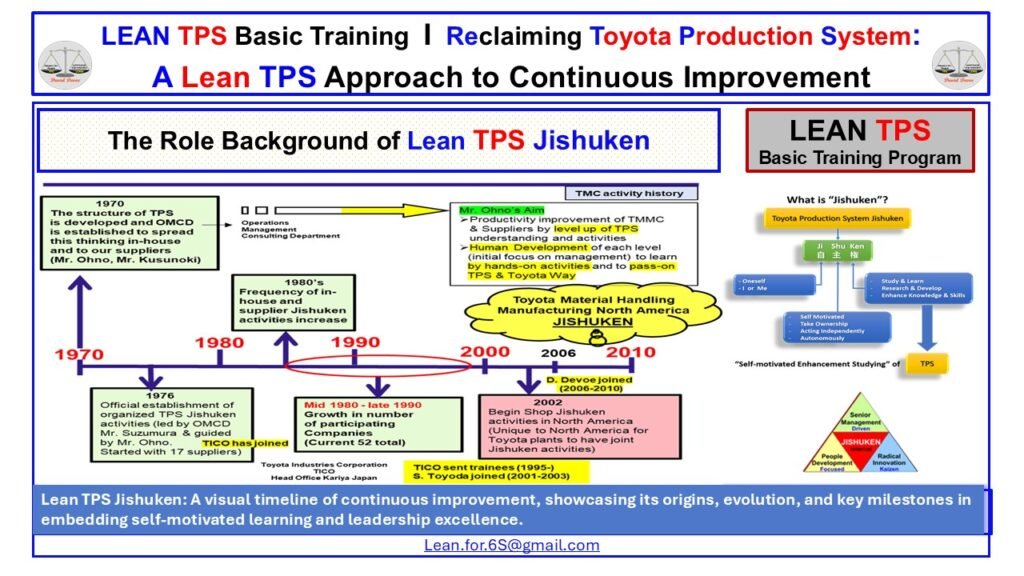

4: Historical Evolution of Jishuken as Leadership Governance

How Jishuken Evolved to Govern Leadership Responsibility as System Complexity Increased

Jishuken originated inside Toyota as a deliberate method for developing leaders capable of governing complex production systems. It was created to ensure that leadership capability was built through direct engagement with real work, not through classroom instruction or delegated analysis. This section traces how Jishuken evolved from early shop floor study into a global leadership governance system that remains central to Lean TPS.

As system complexity increased over time, Jishuken matured to address not only process improvement but also leadership accountability. That evolution is directly relevant today as organizations enter Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments where execution transparency increases and leadership responsibility can no longer be absorbed through informal human adaptation.

Figure 4: Historical Evolution of Jishuken: Leadership capability at Toyota advanced through successive generations of structured study, verification, and knowledge transfer.

Why Jishuken Became Toyota’s Primary Leadership Governance Discipline

This history explains why Jishuken is not a tool, an event, or a training program. It exists to ensure that leadership remains directly accountable for system behavior as complexity increases. Each stage of Jishuken’s evolution reinforced the expectation that leaders must see reality, verify conditions, and own response when abnormality is exposed.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, this historical discipline becomes essential. Humanoids surface abnormality without delay or interpretation. The leadership habits developed through Jishuken are what prevent that transparency from becoming instability. Understanding how Jishuken evolved clarifies why leadership governance must evolve with system capability rather than being replaced by technology.

At its origins in the 1960s and 1970s, Jishuken was developed under Taiichi Ohno and the Operations Management Consulting Division as a method for teaching managers how to improve production flow through direct study. Leaders were required to analyze real processes, measure actual conditions, and verify the effect of changes at the Gemba. The objective was not performance improvement alone but the development of leaders who could distinguish normal from abnormal based on facts.

These early Jishuken activities established a fundamental expectation. Leadership growth and process stability were inseparable. Managers and engineers were assigned real system problems, required to document findings, and expected to explain results to senior leadership. Accountability for learning rested with the leader conducting the study.

As Jishuken matured, observation and time study became standardized practices. Leaders learned to rely on measured facts rather than opinion. Reflection was built into every activity to ensure that learning was captured and verified before progressing. This discipline prevented superficial improvement and reinforced the connection between standards, results, and leadership responsibility.

During Toyota’s global expansion, Jishuken became the primary method for transferring Lean TPS capability without diluting intent. Leaders trained in Japan were responsible for developing the same study discipline in overseas operations. This ensured that TPS remained a living system rather than a static set of tools. Leadership behavior, not documentation, became the carrier of knowledge.

By the 1980s, Jishuken evolved into a formal leadership development structure. Study rhythms, documentation formats, and review practices were standardized. Each activity followed a consistent logic of defining the study theme, collecting data, analyzing causes, testing countermeasures, verifying results, and reflecting on learning. This structure allowed leadership capability to be developed systematically across levels.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Jishuken became central to Toyota’s global governance of Lean TPS. Plants established internal Jishuken programs focused on critical system conditions such as flow, material handling, maintenance, and leadership routines. Local learning was connected to global verification through joint reflection and mentor engagement. Responsibility for system stability remained explicit at every level.

Over time, Jishuken was no longer viewed primarily as an improvement activity. It was recognized as a leadership learning system designed to prevent regression and drift. Its value was measured not only in results but in the organization’s ability to sustain stability as conditions changed. Leaders were developed to govern systems, not react to outcomes.

Today, Jishuken remains the mechanism through which Lean TPS preserves its leadership discipline. Each generation of leaders inherits the responsibility to observe directly, verify conditions, and teach through practice. In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, this legacy is critical. As execution becomes more transparent and abnormalities surface instantly, leadership governance developed through Jishuken is what protects Quality and system integrity.

5: Internal Jishuken as a Leadership Governance System

How Internal Jishuken Develops Leadership Capability through Governed Study at the Gemba

Internal Jishuken is the primary mechanism Toyota uses to develop leadership capability within each plant. It is not classroom instruction and not an improvement event. It is structured learning at the Gemba where leaders are required to study real conditions, verify facts, test countermeasures, and reflect on system behavior. Through repeated participation, leaders develop the judgment required to govern execution rather than react to results.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, Internal Jishuken becomes even more critical. As execution transparency increases and abnormalities surface immediately, leadership must be capable of defining normal, setting escalation logic, and stabilizing processes through disciplined study. Internal Jishuken provides the structure that connects senior leadership responsibility, people development, and Kaizen into one governed learning system.

Figure 5: Internal Jishuken Activities Structure: Leadership capability grows through structured study, reflection, and disciplined improvement embedded in daily management.

How Internal Jishuken Governs Leadership Accountability, Learning, and Kaizen

This structure defines how leadership responsibility is exercised inside the operation. Internal Jishuken ensures that improvement activity is governed rather than delegated. Leaders are expected to participate directly in study, verify conditions themselves, and own the response when abnormality is exposed.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, leadership ownership becomes nonnegotiable. Humanoids execute exactly what is defined and surface deviation without interpretation. When leadership is disconnected from system reality, Quality deteriorates rapidly. Internal Jishuken develops leaders who can govern execution shared between humans and machines by making accountability visible and testable at the Gemba.

Internal Jishuken exists to connect leadership intent with daily system behavior. Leaders study time, sequence, motion, and layout directly at the point of work. Through repeated cycles of observation and verification, they develop the ability to recognize instability, analyze causes, and confirm whether countermeasures actually protect Quality.

Leadership participation is explicit. Senior management does not sponsor improvement from a distance. They walk the Gemba, confirm facts personally, and align study themes with system risk. Their presence establishes that learning and improvement are leadership responsibilities rather than delegated activities.

People development is an integrated outcome of this structure. Cross-functional teams participate together, learning how their work interacts across boundaries. Members develop the ability to connect facts to standards, interpret variation, and participate in disciplined problem solving. Leaders coach thinking rather than directing actions, turning study into sustained capability.

Internal Jishuken also enables disciplined Kaizen. Teams are encouraged to test new layouts, rebalance work, simplify motion, and strengthen visual controls. These experiments are conducted under controlled conditions with Quality and safety protected. Creativity is encouraged, but results are verified before changes are standardized and taught forward.

Each Internal Jishuken follows a consistent study rhythm. Leaders define the study theme based on system risk. Teams collect and visualize data to expose variation. Causes are analyzed through direct verification at the Gemba. Countermeasures are tested in small trials. Results are confirmed. Learning is reflected upon and shared. Standards are updated before the next study begins.

Reflection converts activity into learning. Teams review what was observed, what was tested, what was confirmed, and what must be taught forward. Standardization follows reflection to lock in learning and provide a stable base for the next cycle. Without standardization, improvement fades. With it, leadership capability grows steadily.

Internal Jishuken is sustained through repetition. Each cycle strengthens habits of observation, verification, and accountability. Over time, leaders develop the judgment required to govern increasingly complex systems. In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, this discipline is what prevents silent failure and protects Quality as execution becomes more transparent.

This section establishes Internal Jishuken as a leadership governance system rather than an improvement activity. By integrating leadership participation, people development, and disciplined Kaizen, Internal Jishuken creates a repeatable learning structure that stabilizes execution and prepares leaders to govern systems where human adaptation alone is no longer sufficient.

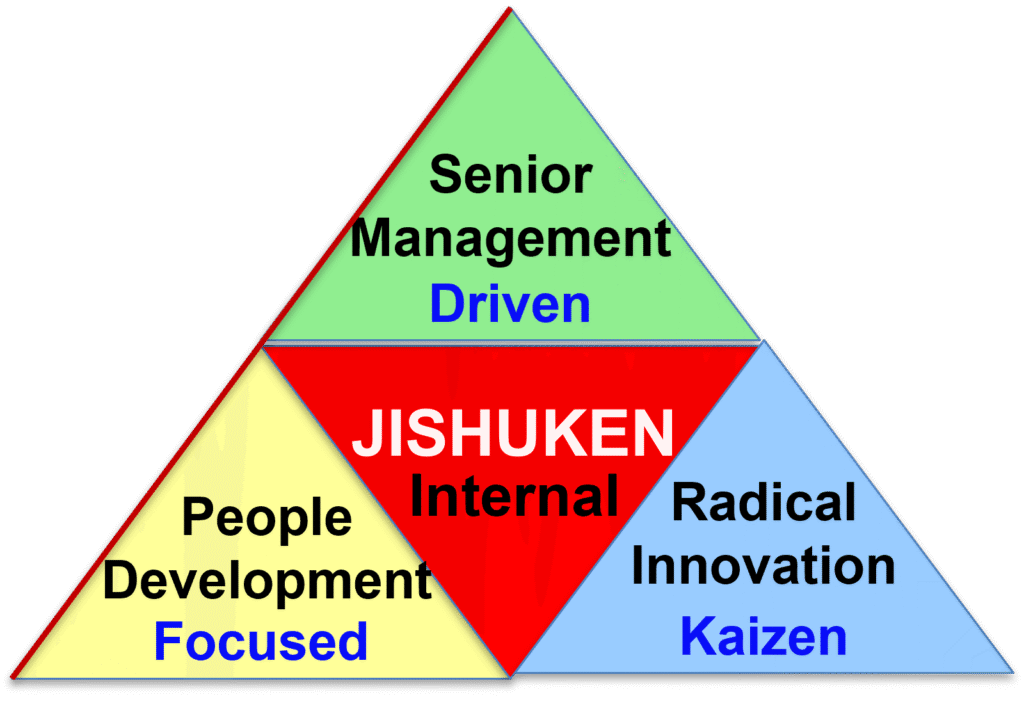

6: Leadership-Driven Learning and the Jishuken Governance Triangle

How Leadership Direction, People Development, and Disciplined Kaizen Are Governed as One System

The Jishuken Triangle describes how Lean TPS aligns leadership accountability, people development, and disciplined Kaizen into a single learning system. It is not a cultural model and not a motivational construct. It defines how leadership governs learning and improvement under real operating conditions.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, this balance becomes critical. As execution becomes explicit and abnormalities are surfaced immediately, leadership must ensure that purpose, capability, and experimentation remain aligned. The Jishuken Triangle explains how Lean TPS prevents learning from fragmenting into isolated improvement activity or uncontrolled innovation.

Figure 6: The Jishuken Triangle: Leadership governance, people capability, and disciplined Kaizen form a balanced system that sustains learning and protects Quality.

How the Jishuken Triangle Prevents Drift, Dependency, and Uncontrolled Improvement

This triangle defines how leadership responsibility is exercised rather than delegated. Each side exists to prevent a specific failure mode. Leadership direction prevents aimless activity. People development prevents dependency on experts. Disciplined Kaizen prevents stagnation without creating instability.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, imbalance creates immediate Quality risk. When leadership direction is weak, humanoids execute undefined intent. When people capability is underdeveloped, escalation breaks down. When Kaizen is uncontrolled, system stability erodes. The Jishuken Triangle ensures that learning remains governed as system transparency increases.

Leadership direction is the first side of the triangle. Leaders define the purpose of study, select themes based on system risk, and establish what must be learned rather than what must be fixed. Leadership responsibility does not end with setting objectives. Leaders participate directly at the Gemba to verify conditions, challenge assumptions, and confirm whether learning is occurring. Direction is established through engagement, not instruction.

People development is the second side of the triangle. Jishuken exists to build capability, not to deliver results through intervention. Participants learn to observe processes, compare conditions to standards, analyze causes, and verify outcomes. Learning occurs through participation in real study rather than explanation. Leaders coach thinking by asking questions, structuring reflection, and ensuring that learning is shared rather than stored.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, this capability becomes essential. Humans retain responsibility for judgment, escalation, and decision making even as execution is shared with machines. Without deliberate capability development, leadership becomes reactive and governance weakens. The people development side of the triangle ensures that ownership remains with humans.

Disciplined Kaizen is the third side of the triangle. Jishuken requires challenge to remain effective. Teams are expected to test new layouts, rebalance work, simplify motion, and strengthen visual controls. These experiments are conducted under controlled conditions with Quality protected. Kaizen introduces learning tension, but Jishuken provides the structure that makes experimentation repeatable and teachable.

The triangle functions only when balanced. Leadership direction without people development creates reliance and compliance. People development without challenge slows learning. Kaizen without governance creates instability. Jishuken integrates all three so that learning strengthens rather than destabilizes the system.

Senior leadership sustains the triangle by reinforcing learning behavior across the organization. Leaders protect time for study, verify learning through evidence, and confirm that standards and escalation logic are clear. Their presence at the Gemba demonstrates that learning precedes decision making. This behavior establishes trust and reinforces that improvement is a shared responsibility.

The Jishuken Triangle creates continuous renewal without loss of control. Each study strengthens leadership judgment, builds capability, and introduces the next challenge. As each side reinforces the others, the organization evolves while maintaining stability. This is how Lean TPS sustains learning without relying on human adaptation to absorb ambiguity.

This section establishes the Jishuken Triangle as a leadership governance model. It explains how Lean TPS aligns purpose, capability, and experimentation to protect Quality in environments where execution transparency exceeds the capacity for informal correction.

7: The Historical Foundations of Jishuken and the Learning Cycle

Scientific Lineage of Jishuken as a Leadership Learning Cycle

Jishuken is grounded in a long lineage of scientific problem solving that links observation, experimentation, verification, and learning. It did not emerge as a technique but as an evolution of how leaders learn to govern systems through facts. This section traces the historical foundations of problem solving that shaped Toyota’s approach and explains how those foundations culminated in Jishuken as a leadership learning cycle.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, this lineage matters. As abnormalities surface immediately and continuously, leadership must rely on disciplined learning cycles rather than intuition or experience-based compensation. Jishuken represents the convergence of scientific method and leadership responsibility.

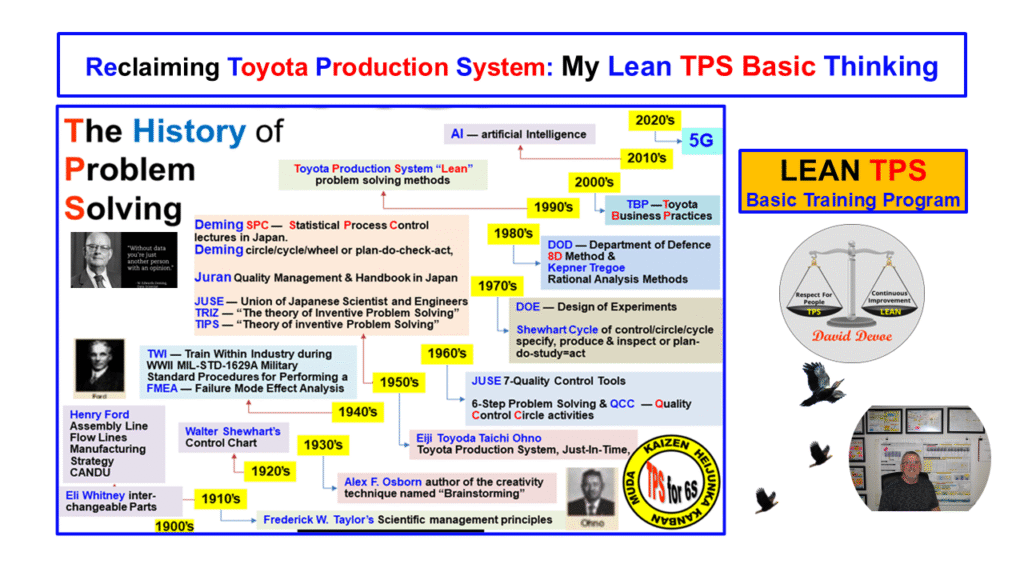

Figure 7: The History of Problem Solving: The evolution of scientific thinking that formed the foundation for Toyota’s Jishuken learning cycle.

Why Historical Learning Cycles Define Modern Leadership Governance

This history explains why Jishuken is not optional and not interchangeable with modern problem-solving frameworks. It exists to ensure that leadership decisions are grounded in verified understanding rather than opinion. As system transparency increases, leadership must be able to distinguish signal from noise, confirm causes, and govern response.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, the tolerance for unverified judgment disappears. Humanoids surface deviation without filtering. Leadership capability must therefore be anchored in a learning cycle that has been proven over generations. Jishuken inherits that discipline.

Scientific problem solving began with early industrial studies that emphasized observation and standardization. Frederick Taylor introduced time and method study to understand work scientifically rather than relying on craft intuition. While limited in its human dimension, this work established the principle that improvement must be based on observable facts.

Walter Shewhart expanded this foundation by introducing statistical thinking. His control charts and concept of variation shifted problem solving from fixing outcomes to understanding process behavior. The Shewhart cycle established that learning occurs through specification, production, inspection, and adjustment. This concept of closed-loop learning would later become central to Toyota’s thinking.

Edwards Deming formalized this logic through the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle. PDCA emphasized hypothesis, testing, verification, and standardization. Deming’s teaching in post-war Japan reinforced that Quality must be built into the process and confirmed through data. Improvement became a disciplined learning activity rather than a corrective reaction.

The Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers embedded these ideas through Quality Circles. These activities introduced structured problem solving to the shop floor, teaching members to observe conditions, analyze causes, and confirm results collaboratively. Quality Circles created the first widespread link between scientific thinking and people development.

Toyota adopted and extended this approach. Leaders such as Kiichiro Toyoda, Taiichi Ohno, and Eiji Toyoda recognized that tools alone were insufficient. Problem solving had to develop people who could think, see, and judge system behavior. Standards became the reference point for learning. Without defined normal, abnormality could not be detected and improvement could not be verified.

As analytical methods expanded through the mid-twentieth century, Toyota selectively absorbed them. Design of Experiments, failure analysis, and structured creativity contributed rigor, but Toyota emphasized simplicity and visibility. Methods were only adopted if they could be practiced at the Gemba and taught through participation.

By the 1980s, Toyota integrated these influences into Jishuken. Under the guidance of OMCD, Jishuken became the advanced form of the learning cycle. Leaders were required to plan, observe, analyze, test, verify, and reflect personally. Learning was no longer separated from leadership responsibility. Improvement and development became inseparable.

Jishuken completed the evolution from technical problem solving to leadership governance. Reflection transformed results into understanding. Standardization preserved learning and enabled knowledge transfer. Teaching became a leadership obligation rather than an instructional role.

This historical progression explains why Jishuken remains relevant as systems evolve. In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, the same principles apply. Scientific thinking, disciplined verification, and structured reflection are what allow leadership to govern systems where execution transparency exceeds human adaptability.

This section establishes Jishuken as the modern expression of a century of scientific problem solving. It connects historical method to contemporary leadership responsibility and explains why Lean TPS continues to rely on disciplined learning cycles to protect Quality as system complexity increases.

8: TPS History – The Lineage That Formed Jishuken

TPS as a Continuous Leadership Learning Lineage

The Toyota Production System did not emerge as a finished framework. It developed through generations of disciplined experimentation, leadership learning, and system refinement. What distinguishes TPS from later interpretations of Lean is not a collection of tools, but the continuity of thinking that connects invention, standardization, and leadership responsibility.

This section traces the historical lineage that shaped TPS and explains how those foundations led to Jishuken as the primary method for leadership learning. The history matters because TPS was designed to make problems visible, not to hide them, and to develop leaders who learn through direct engagement with the system they govern.

Figure 8: The Lineage of the Toyota Production System: Foundational leaders and principles that shaped TPS and established Jishuken as a leadership learning system.

Foundational Principles That Converged into Jishuken

The Origins of Built-In Quality: Sakichi Toyoda

The lineage begins with Sakichi Toyoda and the principle of Jidoka. His automatic loom stopped itself when an abnormal condition occurred, preventing defects from being passed forward. This invention established the idea that quality must be built into the process rather than inspected afterward.

Jidoka placed responsibility with people, not machines. It created the expectation that abnormalities must be surfaced immediately and addressed at the source. This principle became the moral and technical foundation of TPS and later shaped how leadership was expected to respond to problems.

Flow and the Exposure of Problems: Kiichiro Toyoda

Kiichiro Toyoda extended Jidoka into production flow. Faced with limited resources and intense competition, he introduced the concept of Just-in-Time to synchronize production with demand. Flow was not intended to increase speed alone. Its purpose was to expose problems by removing buffers that concealed instability.

By linking timing, sequence, and demand, Kiichiro created conditions where abnormalities could no longer be ignored. Flow became a learning mechanism. Problems surfaced naturally, requiring leaders to respond through understanding rather than reaction.

Standardization and Scientific Thinking: Taiichi Ohno

Taiichi Ohno unified Jidoka and Just-in-Time into an integrated production system. His development of Kanban provided a visual method for controlling flow and revealing deviation. Kanban was not a scheduling tool. It was a communication device that made system behavior visible.

Ohno’s insistence that “where there is no standard, there can be no Kaizen” defined the logic of TPS. Standards established normal. Normal made abnormality visible. Visibility made learning possible. Without standardization, improvement could not be verified and leadership judgment could not be grounded in fact.

From Improvement to Leadership Learning: OMCD and Jishuken

As TPS matured, Toyota recognized that sustaining the system required more than operational discipline. It required leaders who could think scientifically and govern through observation and verification. Through the Operations Management Consulting Division, Jishuken was formalized as the method for developing this capability.

Jishuken required leaders to participate directly in study activities at the Gemba. Themes were selected based on system need. Conditions were observed, data collected, countermeasures tested, and results verified. Reflection was mandatory. Learning was not delegated.

This structure ensured that the thinking behind TPS was preserved as Toyota expanded globally. Leaders learned by engaging the system, not by managing reports.

Preserving the System Through Generations: Nomura and Global Continuity

The continuity of TPS thinking was carried forward by OMCD-trained Sensei such as Sadao Nomura. Through global Jishuken activities and mentorship, the principles of verification, reflection, and leadership accountability were transferred beyond Japan.

This continuation demonstrates that TPS is not a historical artifact. It is a living system sustained through disciplined teaching and practice. Jishuken ensures that leadership learning remains aligned with system reality rather than drifting into abstraction.

Standardization as the Foundation of Learning

The quote shown in the image captures the unifying principle of this lineage. Standardization is not constraint. It is the condition that enables learning. Without a defined normal, leadership cannot detect abnormality, confirm improvement, or protect Quality.

Every generation of TPS leadership reinforced this logic. Stability enables learning. Learning enables improvement. Improvement develops people. This cycle is the essence of the Thinking People System.

TPS as a Living Learning System

The history of TPS shows that it was never designed as a set of tools to be copied. It was designed as a system that develops people through structured learning. Jishuken represents the highest expression of this intent. It connects philosophy, process, leadership, and Quality into one disciplined practice.

This lineage explains why TPS remains relevant as systems evolve. As execution becomes more transparent and less forgiving, leadership must rely on verified learning rather than intuition. Jishuken preserves that capability by keeping leadership grounded in facts, reflection, and responsibility.

9: Operations Management Consulting Division (OMCD) and the Globalization of Jishuken

OMCD as the Global Steward of TPS Leadership Thinking

The Operations Management Consulting Division was created to protect the integrity of the Toyota Production System as it expanded beyond its original plants. OMCD was not established to audit performance or deploy tools. It was created to develop leadership capability through structured study, reflection, and direct engagement with real work. Through OMCD, Jishuken became Toyota’s formal mechanism for transferring thinking, not copying practice.

OMCD ensured that TPS remained a learning system governed by facts, standards, and leadership accountability. This section explains how OMCD globalized Jishuken while preserving its purpose as a leadership development discipline.

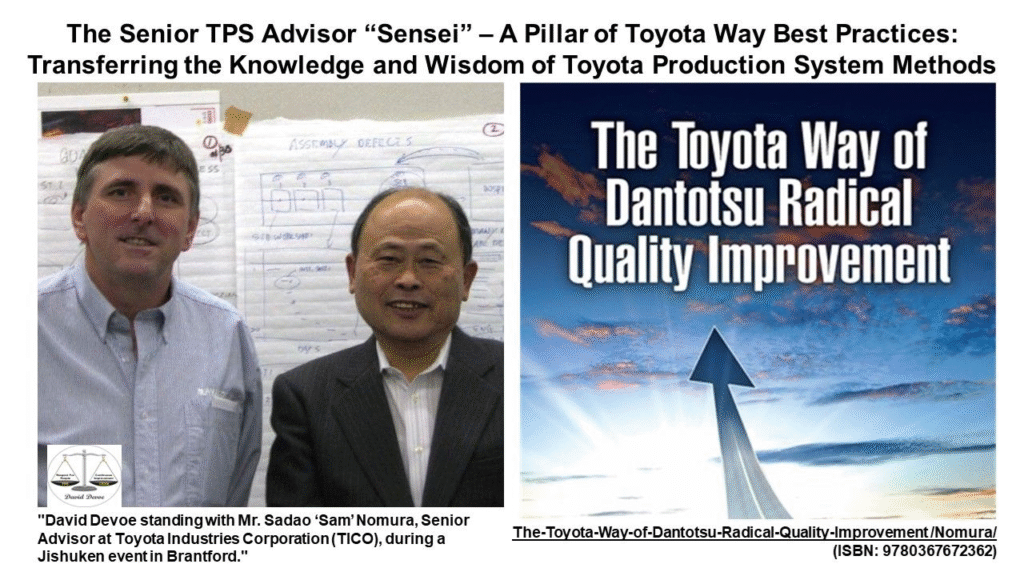

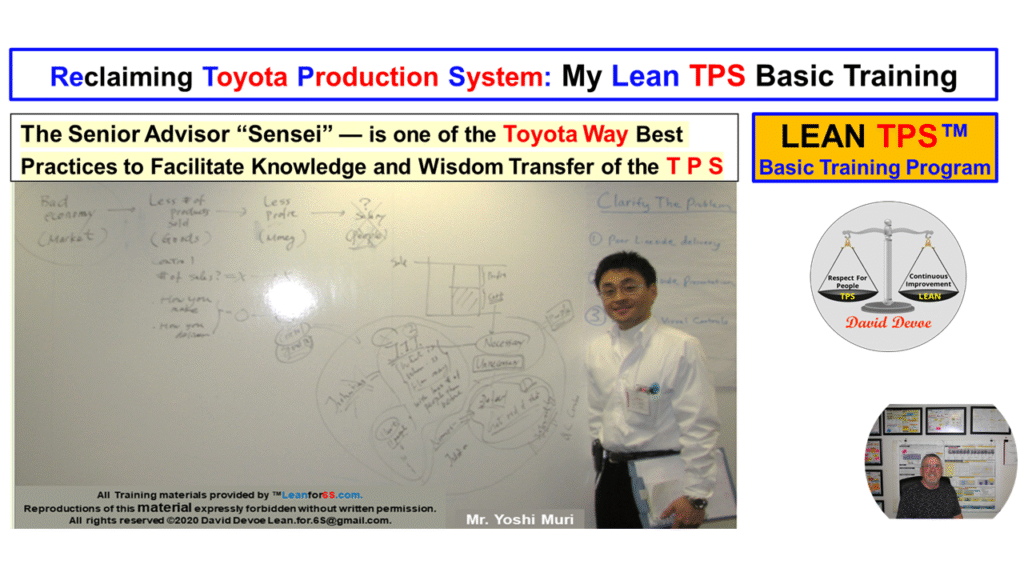

Figure 9: The Senior TPS Advisor “Sensei”: OMCD Sensei preserved Toyota Production System thinking by developing leaders through direct study, verification, and reflection at the Gemba.

How Sensei Transferred Judgment, Not Tools

OMCD was established under Taiichi Ohno to consolidate and safeguard the Toyota Production System as a coherent way of thinking. Its responsibility was not improvement results alone, but the development of leaders who could sustain improvement through disciplined study. OMCD consultants acted as internal advisors whose role was to teach leaders how to see, think, and verify.

Unlike external consulting models, OMCD did not solve problems for others. Consultants embedded themselves in plants to guide Jishuken activity, requiring leaders to observe directly, confirm facts, and take ownership of system behavior. This structure ensured that TPS remained rooted in learning rather than compliance.

The Sensei Role and Leadership Accountability

Within OMCD, the Sensei role represented mastery of both philosophy and method. Sensei did not provide answers. They created conditions where leaders were forced to confront gaps between actual conditions and defined standards. Through questioning, observation, and challenge, Sensei transferred judgment rather than instruction.

This approach reinforced a core TPS principle: leadership accountability cannot be delegated. Leaders were expected to verify data themselves, test countermeasures personally, and reflect openly on results. Sensei ensured that learning occurred through engagement, not authority.

The presence of OMCD-trained Sensei, including Mr. Sadao Nomura, exemplifies this discipline. Their work demonstrated that leadership development and process improvement are inseparable.

Formalizing Reflection as a System Requirement

OMCD institutionalized reflection as a mandatory element of improvement. Every Jishuken followed a defined sequence that ended with structured reflection. Teams documented what was learned, what was confirmed, and what standards required revision. This prevented learning loss and ensured that improvement strengthened system understanding.

Reflection connected technical results to leadership growth. It transformed activity into knowledge and knowledge into capability. OMCD’s discipline of reflection later influenced the A3 format, reinforcing the requirement that thinking, evidence, and learning be visible.

Teaching Through Seeing

OMCD defined leadership as the ability to see system behavior clearly. Leaders were expected to stand at the point of work, compare actual conditions to standards, and understand cause and effect before acting. Teaching was inseparable from seeing. Leaders who could not explain what they observed had not yet learned.

This expectation reshaped leadership behavior. Decision making slowed until understanding was verified. Authority was replaced by evidence. Learning replaced instruction. Through this practice, TPS became resilient as it expanded across cultures and regions.

Globalizing Jishuken Without Dilution

As Toyota expanded globally, OMCD became the mechanism for knowledge transfer. OMCD-trained advisors were assigned to overseas operations to guide Internal and Plant-Wide Jishuken. The same sequence was followed everywhere: define theme, observe, analyze, test, verify, reflect, and standardize.

This consistency prevented drift. While local conditions varied, the method of learning did not. OMCD ensured that TPS remained a system of thinking rather than a set of localized practices.

OMCD’s Enduring Contribution

OMCD proved that improvement can only be sustained when leadership capability is developed deliberately. By embedding learning into daily management through Jishuken, OMCD preserved TPS as a living system. Its consultants became guardians of Toyota’s learning culture, ensuring that respect for people and scientific thinking remained inseparable.

Every Jishuken conducted today traces its structure to OMCD’s discipline. The division’s legacy is not performance metrics but generations of leaders capable of governing complex systems through observation, verification, and reflection.

Conclusion

The Operations Management Consulting Division transformed Jishuken into Toyota’s global leadership development system. By standardizing study, enforcing reflection, and maintaining accountability at the Gemba, OMCD ensured that TPS could scale without losing its foundation. Through OMCD, Toyota demonstrated that lasting improvement is not deployed. It is learned, verified, and taught forward through disciplined leadership practice.

10: North American Application of Jishuken

Transferring Jishuken Outside Japan Without Dilution

The application of Jishuken in North America marked a critical test of whether the Toyota Production System could be transferred without dilution. At Toyota BT Raymond in Brantford, Ontario, and Toyota Material Handling Manufacturing North America, Jishuken was not introduced as a program or initiative. It was introduced as a leadership learning discipline governed by observation, verification, and reflection at the Gemba.

Under the guidance of OMCD-trained Sensei, these organizations applied the same study structure practiced in Japan. The objective was not performance acceleration. The objective was leadership capability development and system stability through disciplined learning.

Figure 10: North American Application of Jishuken: Jishuken applied in North America as a leadership development system grounded in direct observation, reflection, and standardization.

How OMCD Discipline Was Practiced in North America

When Jishuken was introduced at Toyota BT Raymond and TMHMNA, its purpose remained unchanged. Leaders were required to learn through direct engagement with real work. Japanese Sensei guided North American leaders through the same sequence used inside Toyota: theme definition, observation, data collection, cause analysis, countermeasure testing, verification, reflection, and standardization.

This structure made leadership behavior visible. Managers were expected to stand at the process, verify facts personally, and explain system behavior based on evidence. Analysis could not be delegated. Learning was confirmed only through direct observation and reflection.

At both sites, this discipline created a shared understanding of what leadership meant inside TPS. Leadership was defined by the ability to see, verify, teach, and sustain improvement.

Adapting Without Dilution

Applying Jishuken in North America required cultural adaptation, not methodological compromise. Communication styles, decision habits, and expectations around speed differed from Japan. Sensei invested time establishing trust and explaining purpose before enforcing rigor.

Early misunderstanding was common. Many leaders initially interpreted Jishuken as an advanced problem-solving activity. Through repetition, its true purpose became clear. Jishuken existed to develop judgment, not solutions. Results mattered, but learning mattered more.

Visual study boards, A3s, and reflection summaries were used to make thinking explicit. This reduced ambiguity and allowed learning to transcend language and cultural differences. Facts became the common reference point.

Leadership Development Through Practice

At Toyota BT Raymond and TMHMNA, Jishuken became the primary structure for leadership development. Leaders learned by studying real problems with cross-functional teams. Engineers, supervisors, and managers participated together, reinforcing shared responsibility for system behavior.

Reflection was mandatory. After each study, teams documented what was observed, what was learned, and what standards required change. These reflections made leadership growth visible and repeatable.

Senior leadership participation was critical. When executives attended Gemba reviews and reflection sessions, it reinforced that learning and verification were leadership obligations. This consistency aligned behavior across levels and sustained the discipline.

Nomura Sensei and Dantotsu Quality

A defining influence in North America was the mentorship of Mr. Sadao Nomura, Senior Advisor and OMCD-trained Sensei. His teaching emphasized Dantotsu Quality, the pursuit of being the best through clarity, precision, and prevention of failure.

Nomura taught that quality is not enforced through inspection. It is governed through system design and leadership behavior. Leaders were expected to verify facts personally and define standards that prevent ambiguity.

His mentorship ensured that Jishuken in North America remained faithful to Toyota’s thinking while addressing local realities. The result was leadership capability grounded in the same discipline practiced in Japan.

Reflection as a Leadership Standard

Reflection became the defining characteristic of North American Jishuken. Teams documented technical findings, leadership behaviors, communication gaps, and system weaknesses immediately after action. Reflection transformed experience into knowledge.

This discipline reinforced that Jishuken is a people development system as much as a technical one. Each reflection established a new baseline for how leaders observe, decide, and teach. Learning was not left to memory. It was made explicit.

Integration into Lean TPS Basic Training

The experience gained through Jishuken at Toyota BT Raymond and TMHMNA became the foundation of Lean TPS Basic Training. Leaders who participated in studies became teachers, transferring learning through structured training grounded in real examples.

Training focused on observation, verification, and reflection rather than presentation. Participants studied actual conditions at the Gemba and confirmed understanding through discussion and evidence. This ensured that training reinforced thinking, not tools.

Jishuken was not separated from training. It became the core learning engine behind it.

Leadership Continuity and System Stability

Through Jishuken and Lean TPS Basic Training, both organizations built a self-sustaining leadership development system. Leaders were expected to teach forward what they learned, creating continuity across generations.

This prevented dependency on external experts and maintained consistency in leadership behavior. Improvement became normal work. Reflection became normal decision making.

Conclusion

The North American application of Jishuken demonstrated that the Toyota Production System can be transferred without losing its integrity when learning discipline is preserved. By applying the OMCD method and reinforcing Dantotsu Quality, Toyota BT Raymond and TMHMNA developed leaders capable of governing complex systems through observation, verification, and reflection. The Thinking People System proved universal wherever leadership accepts responsibility to learn by doing.

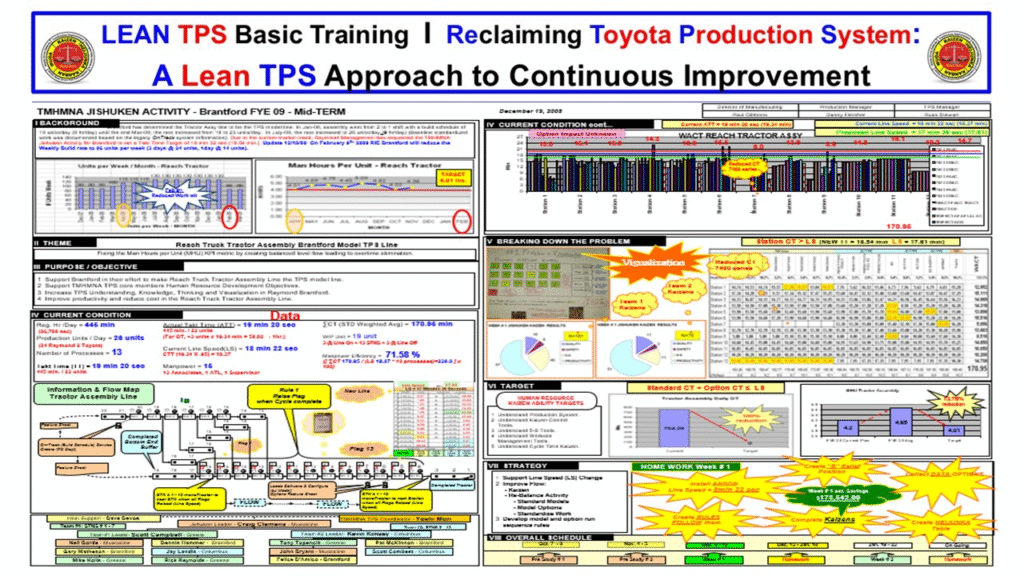

11: Brantford Jishuken Kickoff A3 (FYE09)

Establishing the Jishuken Learning Baseline at Toyota BT Raymond

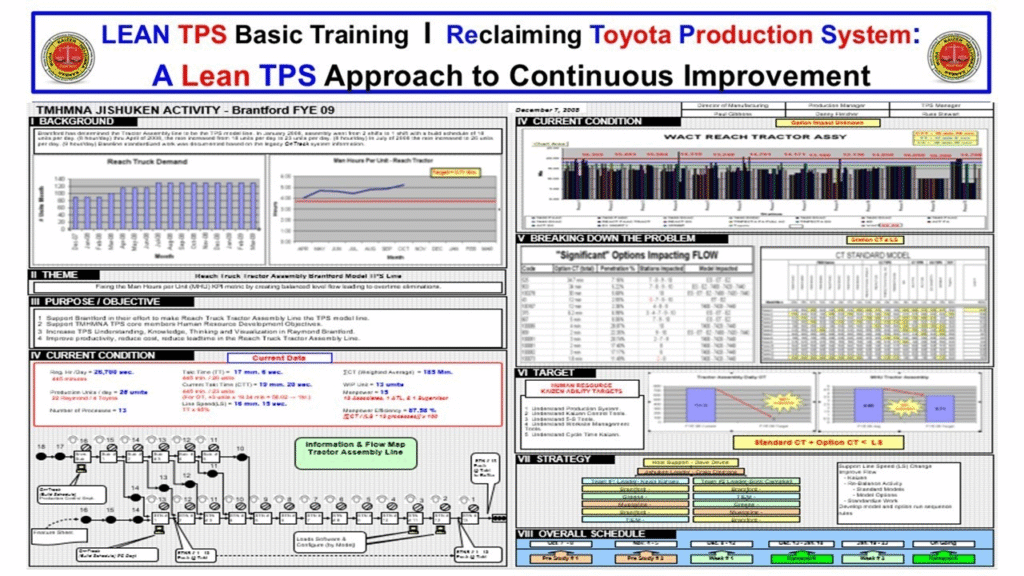

The Brantford Jishuken Kickoff A3 for the fiscal year ending 2009 marked the formal launch of the Jishuken learning system at Toyota BT Raymond in North America. Developed under the guidance of OMCD-trained Sensei, this A3 established the baseline structure for how Jishuken studies would be framed, executed, verified, and reflected upon. It defined Jishuken not as a project but as a leadership governance mechanism that integrates process improvement, capability development, and Quality protection.

Figure 11 – Brantford Jishuken Kickoff A3 (FYE09): Baseline A3 defining theme, objectives, study structure, and leadership learning framework for the Reach Truck Tractor Assembly Jishuken at Toyota BT Raymond.

How the A3 Governs Leadership Learning, Verification, and Reflection

The purpose of the kickoff A3 was to align leadership learning with process improvement through a disciplined study of the Reach Truck Tractor Assembly line. The intent was not limited to improving performance metrics. It was to teach leaders how to observe flow, verify facts, analyze variation, and confirm results using a standardized learning method. The A3 served as the single reference point connecting technical analysis with leadership behavior.

Theme and Learning Objective

The Jishuken theme addressed conditions limiting stable flow in the Reach Truck Tractor Assembly process. The learning objective was to develop leadership capability in observing process behavior scientifically, distinguishing normal from abnormal, and confirming improvement through data rather than assumption. Leadership learning and process improvement were treated as inseparable outcomes of the study.

Current Condition Analysis

The current condition was documented using time studies, Standardized Work Combination Tables, layout diagrams, and workload distribution charts. Data revealed imbalance across stations, variation in work content driven by option mix, and instability in material presentation timing. Visualizing these conditions created shared understanding and established a factual baseline for study.

Problem Breakdown and Target Setting

Confirmed gaps were broken down into measurable factors affecting flow, workload balance, and stability. Targets were set to reduce variation, improve balance across stations, and stabilize material presentation. Targets reflected both performance outcomes and leadership learning expectations, reinforcing that improvement is incomplete without increased capability.

Strategy and Countermeasure Development

Countermeasures focused on standardizing work sequence, rebalancing tasks, improving part presentation, and strengthening coordination between assembly and material handling. All proposals were tested under controlled conditions at the Gemba. Results were verified using actual production data before adoption. The A3 format allowed teams to review thinking visually and learn from both successful and unsuccessful trials.

Verification through PDCA and Standardization

Verification occurred through Mid-Term and Final A3 reviews. Mid-Term data confirmed that countermeasures were effective and repeatable. Man-hours per unit were reduced from 185 minutes to 160 minutes, work balance improved, and flow interruptions caused by option differences were reduced.

The Final A3 documented standardization activities. Updated Standardized Work, training materials, visual controls, and audit checks ensured that gains held under daily operating conditions. Before-and-after charts confirmed stability across shifts and volume changes. Verification confirmed both process improvement and leadership learning.

Leadership Development and Reflection

Leadership learning was verified through structured reflection. Core members presented findings, data, and lessons learned to management and cross-functional teams. Presentations emphasized explanation of method and thinking, not results alone. Reflection sessions captured what leaders observed, how their understanding changed, and what required further study. Reflection closed the learning loop and prepared the next Jishuken theme.

Results and Knowledge Transfer

The kickoff Jishuken produced measurable improvements in flow stability and workload balance while developing leaders capable of leading structured studies. The A3 became the standard model for subsequent Jishuken activities at Toyota BT Raymond and later at TMHMNA. Knowledge was transferred horizontally and vertically through documented standards and leader-led teaching.

A Continuous Learning Framework

The Brantford Jishuken Kickoff A3 demonstrated that verification sustains learning. When improvements are confirmed through data, standardized, and reflected upon, they become part of daily management. This discipline transformed Jishuken from a project-based activity into a continuous learning framework that strengthens people, processes, and Quality together.

Verification of Learning through PDCA, Standardization, and Data Based Reflection

To complete the kickoff A3, Toyota BT Raymond created Mid Term and Final A3s that documented how improvements and learning were verified. This verification process transformed Jishuken from a project into a sustainable learning system.

Mid Term Verification

The Mid Term A3 confirmed that countermeasures were effective and repeatable. Data showed:

• Man hours per unit dropped from 185 minutes to 160 minutes

• Work balance between stations improved

• Flow interruptions caused by option differences were reduced

• Layout and sequencing changes stabilized material presentation

Time studies and visual charts verified that improvements were being sustained under normal operating conditions.

Final A3 and Standardization

The Final A3 documented how successful countermeasures were standardized. Teams updated:

• Standardized Work charts

• Operator training materials

• Visual controls

• Audit checklists

Daily production data confirmed that gains held even as volume and model mix changed. Before and after charts demonstrated stability across actual operating shifts.

Leadership Learning and Presentation

Leadership development was verified through structured presentations. Core members presented findings, data, and lessons learned to management and cross functional teams. Presentations emphasized explanation of method, not only results. Reflection captured how leaders thought, what they misunderstood, and how their understanding changed.

Reflection Insights

Reflection panels highlighted key learning points:

• Results must be confirmed through data

• Standards must be reviewed and reinforced to hold gains

• Reflection and teaching complete the learning loop

These insights became the starting point for the next Jishuken cycle.

A Continuous Learning Framework

Verification demonstrated that learning sustains progress. When improvements are measured, standardized, and reflected upon, they become part of daily management. This discipline transformed Jishuken from a project based activity into a continuous learning framework that strengthens people, processes, and performance together.

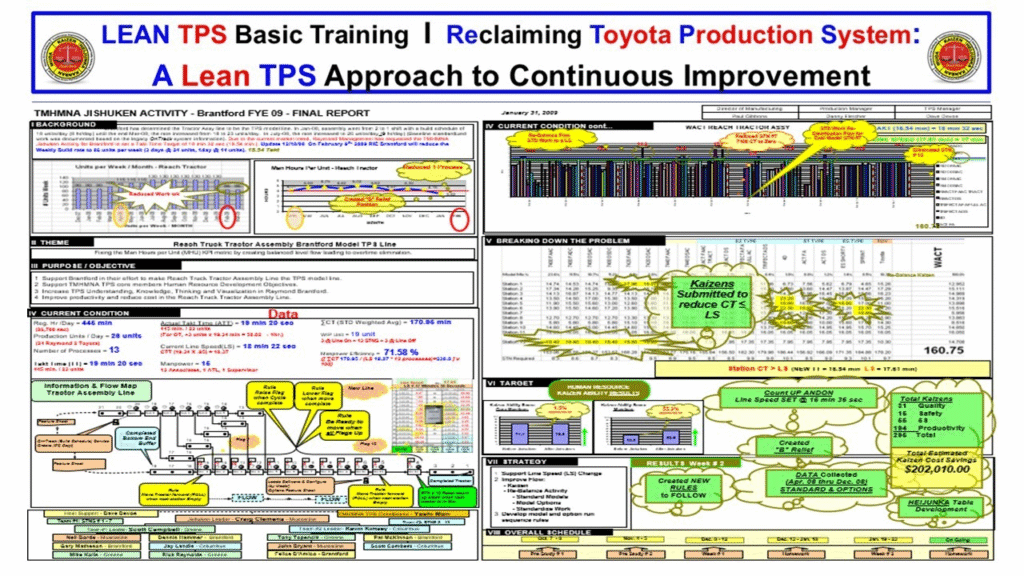

12: Brantford Jishuken Mid-Term A3 (FYE09)

Verifying Execution and Leadership Learning Through Mid-Term PDCA

The Brantford Jishuken Mid-Term A3 for the fiscal year ending 2009 marked the transition from planning to verified execution at Toyota BT Raymond. This stage focused on testing countermeasures, confirming results through data, and developing scientific thinking through structured reflection. The Mid-Term A3 functioned as the primary mechanism for verifying both process improvement and leadership learning within the Jishuken system.

Figure 12 – Brantford Jishuken Mid-Term A3 (FYE09): Mid-Term A3 documenting PDCA execution, countermeasure testing, data verification, and leadership reflection during the Brantford Jishuken study.

How Countermeasure Testing, Data Verification, and Reflection Confirm Learning

The purpose of the Mid-Term A3 was to confirm whether proposed countermeasures from the kickoff study were effective, repeatable, and aligned with the Jishuken learning objectives. This stage reinforced that improvement is not validated by intent or effort but by evidence. The A3 provided a structured record connecting observed results, leadership behavior, and learning confirmation.

Transition from Planning to Execution

By the Mid-Term stage, countermeasures had been implemented on the Reach Truck Tractor Assembly line. Leaders shifted from analysis to execution while maintaining disciplined observation. This transition tested whether the study method held under real operating conditions. The Mid-Term A3 ensured that changes were not temporary fixes but controlled experiments evaluated against clear expectations.

Verification through PDCA

The Mid-Term A3 emphasized the Check and Act phases of PDCA. Time studies, workload balance charts, and flow data were used to confirm whether improvements achieved the intended effect. Data showed reductions in variation, improved line balance, and more stable material presentation.

Verification extended beyond results. Leaders were required to explain why countermeasures worked or did not work. This reinforced the principle that learning is confirmed through understanding cause and effect, not through outcome alone.

Standardization as Evidence of Learning

Standardization was treated as proof of learning. Countermeasures that demonstrated consistent results were incorporated into Standardized Work charts, combination tables, and visual controls. The A3 documented these changes, ensuring that the new baseline was explicit and observable.

This step prevented regression and ensured that future Jishuken studies would begin from a higher standard. Standardization confirmed that improvement had transitioned from experiment to normal condition.

Reflection at the Gemba

Reflection occurred continuously throughout the Mid-Term stage. Leaders participated directly at the Gemba, recording observations, results, and questions. Reflection sessions compared expected outcomes with actual conditions and highlighted gaps in understanding.

OMCD-trained Sensei guided reflection by asking leaders what they saw, what they expected, and what they learned. These discussions exposed assumptions, corrected misunderstandings, and strengthened scientific thinking. Reflection was structured, factual, and inseparable from execution.

Development of Scientific Thinking

The Mid-Term A3 strengthened scientific thinking by requiring leaders to treat each countermeasure as a hypothesis. Leaders learned to test ideas deliberately, analyze variation, and verify conclusions through evidence. Over time, this disciplined approach replaced intuition-based decision making with fact-based reasoning.

Through repetition, leaders developed confidence in studying unfamiliar problems. This capability is central to sustaining continuous improvement under changing conditions.

Leadership Development and Teaching

Leadership development was verified through presentation and teaching. Core members presented Mid-Term findings to management and cross-functional teams, explaining both results and method. Emphasis was placed on how conclusions were reached rather than on success alone.

This teaching requirement ensured that learning became organizational rather than individual. Leaders strengthened their own understanding by explaining it to others, reinforcing the Thinking People System.

Results and Learning Confirmation

The Mid-Term A3 confirmed measurable improvement in flow stability, workload balance, and takt adherence. More importantly, it confirmed growth in leadership capability. Leaders demonstrated improved observation, clearer reasoning, and greater discipline in verification.

Learning was visible, documented, and transferable. The Mid-Term stage ensured that improvement was progressing as a system, not as isolated activity.

Continuity toward Final Verification

The Mid-Term A3 concluded with identified gaps, open questions, and focus areas for the Final A3. This ensured continuity in learning and prevented premature closure. Each Mid-Term review became the starting point for deeper study rather than an endpoint.

A Verified Learning System

The Brantford Jishuken Mid-Term A3 demonstrated that reflection, standardization, and PDCA form a single learning system. When leaders verify results through data, reflect at the Gemba, and teach what they learn, improvement becomes repeatable and sustainable. This stage confirmed that Jishuken functions as a leadership development system grounded in scientific thinking and Quality protection.

13: Brantford Jishuken Final A3 (FYE09)

Confirming Stability, Standardization, and Leadership Learning at Cycle Completion

The Brantford Jishuken Final A3 for the fiscal year ending 2009 marked the completion of the first full Jishuken learning cycle at Toyota BT Raymond. This stage confirmed that improvement, reflection, and leadership development had been integrated into a repeatable system. The Final A3 consolidated verified results, standardized learning, and leadership reflection into a single visible record, demonstrating how Jishuken sustains both process stability and leadership capability.

Figure 13: Brantford Jishuken Final A3 (FYE09): Final A3 consolidating verified improvements, standardized work updates, and leadership reflection from the Reach Truck Tractor Assembly Jishuken at Toyota BT Raymond.

How Verified Results, Standardization, and Reflection Close One Learning Cycle and Launch the Next

The purpose of the Final A3 was to confirm that improvements achieved during the Kickoff and Mid-Term stages were stable, repeatable, and governed by clear standards. This stage verified that learning had been absorbed into daily management rather than remaining dependent on project activity or individual effort. The Final A3 functioned as the formal closure of one learning cycle and the starting point for the next.

Verification of Results through Data

The Final A3 compiled confirmed results from the Mid-Term stage using actual production data, time studies, and visual performance charts. Improvements in takt adherence, man machine balance, and flow stability were validated under normal operating conditions.

Each improvement was linked to its original problem analysis and countermeasure rationale. Verification at the Gemba confirmed that gains were not temporary and that variation had been reduced in a controlled manner.

Standardization as System Confirmation

Standardization was the primary measure of completion. Countermeasures that demonstrated consistent results were written into Standardized Work documents, training materials, visual controls, and audit routines.

No improvement was considered complete without a defined standard and a method to confirm adherence. This reinforced leadership accountability for sustaining results and ensured that future studies would begin from a higher baseline.

Visible Reflection and Leadership Accountability

The Final A3 emphasized visible reflection as a leadership discipline. Reflection sessions were conducted at the Gemba using the A3 as the focal point. Leaders were required to explain what was learned, how results were confirmed, and what standards were changed.

OMCD-trained Sensei guided these discussions to maintain focus on facts, clarity, and learning. Reflection was not treated as opinion sharing but as verification of understanding and ownership.

Consolidation of Leadership Learning

Leadership learning was documented alongside technical results. Leaders recorded insights related to observation, data confirmation, communication, and decision making. This ensured that leadership development advanced in parallel with process improvement.

Presentations to management and cross-functional teams emphasized method and thinking rather than outcome alone. Teaching reinforced learning and transferred capability beyond the core Jishuken team.

Continuity into the Next Jishuken Cycle

The Final A3 concluded by identifying remaining gaps and defining the next Jishuken theme. Issues related to material flow consistency, ergonomic variation, and communication were documented as inputs for the following fiscal year.

This confirmed that Jishuken operates as a continuous learning system. Each completed cycle provides the foundation for the next without loss of knowledge or momentum.

A Verified Learning System

The Brantford Jishuken Final A3 demonstrated that sustained improvement depends on the disciplined connection between PDCA, standardization, and reflection. When learning is verified through data, embedded in standards, and reinforced through visible leadership behavior, improvement becomes self sustaining.

This Final A3 confirmed that Jishuken at Toyota BT Raymond had transitioned from an event based activity into a governed learning system aligned with the Thinking People System.

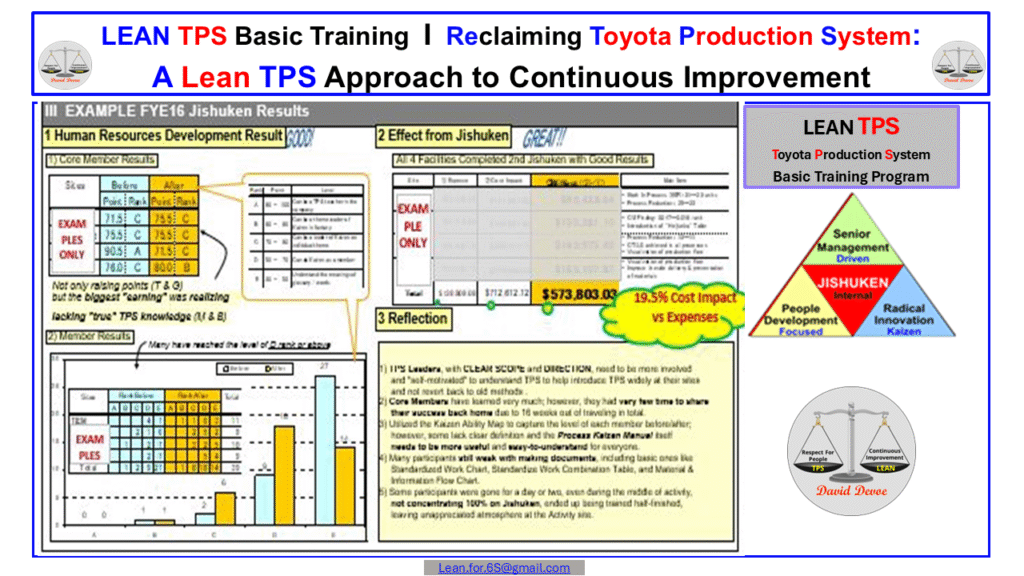

14: FYE2016 Jishuken Results

Confirming Scaled Leadership Development and System Performance Across North America

The FYE2016 Jishuken Results A3 summarized the outcomes of Jishuken activity across Toyota BT Raymond, TMHMNA, and associated North American plants. This stage confirmed that Jishuken had matured into a standardized management and leadership development system operating consistently across sites. Results demonstrated that improvement, reflection, and people development were functioning as one integrated system within Lean TPS.

Figure 14: FYE2016 Jishuken Results: Consolidated A3 showing leadership development outcomes and verified performance results from Jishuken activity across North American Toyota operations.

How Aggregated Jishuken Results Validate Consistency, Capability Development, and Governance at Scale

The purpose of the FYE2016 Results A3 was to confirm that Jishuken could operate at scale while maintaining consistency in thinking, method, and leadership behavior. Unlike earlier site specific studies, this A3 aggregated results across multiple plants using the same Jishuken structure, allowing leadership capability and performance outcomes to be compared and shared.

Verification of Results through Data

Performance results were verified using production data, cost impact analysis, safety records, and quality indicators. Improvements were not reported as isolated gains but linked directly to completed Jishuken cycles. Data confirmed reductions in variation, improved flow stability, and measurable cost impact tied to standardized countermeasures.

Each site demonstrated that improvements held under normal operating conditions, confirming that learning had been embedded into daily management rather than dependent on special activity.

Human Resource Development Results

Leadership development was treated as a primary result, not a secondary benefit. Reflection records showed measurable improvement in observation skill, problem definition, coaching behavior, and confirmation of facts at the Gemba.

Supervisors and managers demonstrated the ability to lead Jishuken independently, apply PDCA without external direction, and standardize learning through teaching. This confirmed that capability development had become self sustaining.

Team and Participation Results

Team participation increased across sites as Jishuken became part of regular work rather than a special project. Cross functional teams engaged in shared analysis, reflection, and follow up.

Standardized reflection practices created consistency in how teams reviewed results and captured learning. This strengthened alignment, communication, and shared ownership of improvement outcomes.

Standardization as System Confirmation

Standardization served as the governing mechanism that sustained results. Successful countermeasures were written into Standardized Work, training materials, visual management systems, and audit routines.

This ensured that improvements were protected against regression and that future Jishuken cycles began from a higher baseline. Leadership accountability for maintaining standards was visibly reinforced.

Reflection as a Management Discipline

Reflection was fully integrated into leader standard work. Leaders facilitated structured review sessions focused on facts, learning, and next steps rather than explanation or justification.

Reflection converted results into organizational knowledge and reinforced humility, discipline, and scientific thinking. This practice confirmed that learning, not activity, was the core output of Jishuken.

Yokoten and Cross Site Learning

Results were shared across plants through structured Yokoten. A3s were reviewed jointly, allowing sites to adopt proven countermeasures and leadership practices rapidly.

This horizontal transfer of knowledge ensured consistency across North America while accelerating capability development. Jishuken functioned as a regional learning network rather than isolated local efforts.

A Verified Continuous Improvement System

The FYE2016 Results A3 confirmed that Jishuken had become a repeatable, scalable system for continuous improvement and leadership development. Performance gains in cost, quality, delivery, and safety were the visible outcomes of disciplined learning practiced daily.

The results demonstrated that Lean TPS sustains improvement when leaders study facts, reflect openly, standardize learning, and teach others. This confirmed the Thinking People System in operation across North America.

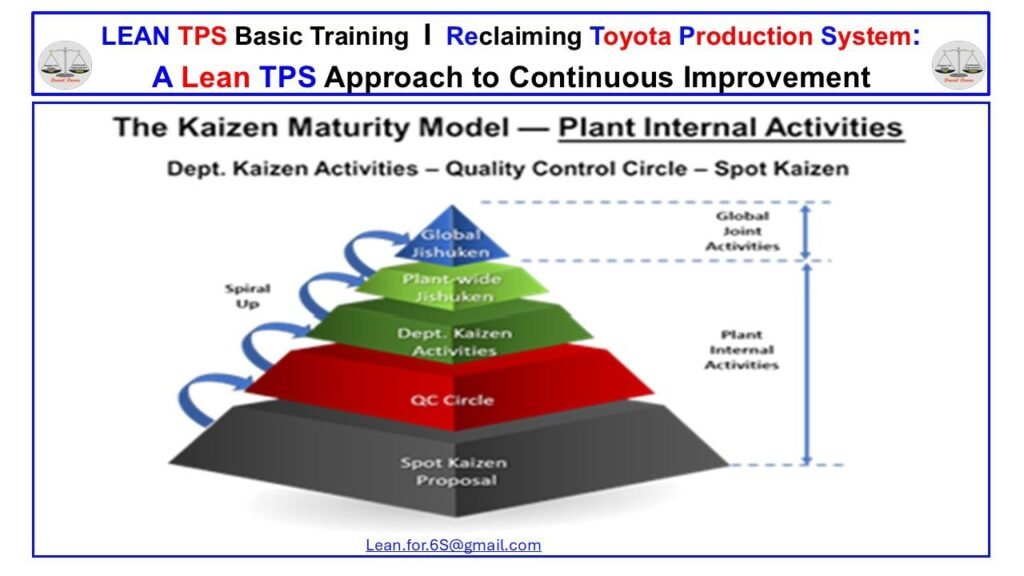

15: Inspiring Leaders to Drive Jishuken

Leadership Ownership as the Final Condition for a Sustained Jishuken System

The final stage of the Jishuken system is leadership. Once the learning structure exists, its effectiveness depends entirely on how leaders think, participate, and reflect. In Lean TPS, leadership is not authority or instruction. It is visible engagement in study, confirmation of facts, and disciplined reflection. This section explains how Jishuken becomes a leadership development system when leaders take ownership of learning and model scientific thinking in daily work.

Figure 15: Inspiring Leaders to Drive Jishuken: Leadership-driven Jishuken environment where reflection, study, and standardized learning are made visible and shared across the organization.

How Leadership Participation, Reflection, and Teaching Sustain the Jishuken Learning Spiral

In Lean TPS, leaders are expected to participate directly in Jishuken. They observe at the Gemba, confirm conditions, and engage in reflection alongside teams. Leadership credibility is established through presence and understanding rather than position.

This behavior reinforces that learning is a responsibility, not a delegation.

Reflection as a Leadership Discipline

Reflection is the defining leadership behavior within Jishuken. After each study cycle, leaders explain what was observed, what was expected, what occurred, and what was learned. This discipline transforms activity into capability.

Reflection makes thinking visible and allows learning to be shared, challenged, and standardized.

Developing Thinking Leadership

Jishuken develops leaders who think before they act. Leaders learn to frame problems clearly, verify facts personally, and test ideas through controlled study. Over time, this builds confidence grounded in understanding rather than intuition.

Thinking leadership is measured by the ability to explain cause and effect, teach others, and sustain standards.

Linking Kaizen Maturity and Leadership Growth

The Kaizen maturity structure shown in the model demonstrates that leadership development follows the same progression as improvement. Learning begins with individual problem solving and expands through department, plant, and global study.

Leaders advance by demonstrating the ability to manage greater complexity through disciplined thinking and reflection.

Respect for People Through Learning

Respect for People is expressed through how leaders develop others. In Jishuken, leaders are responsible for creating an environment where problems can be studied without blame and learning is shared openly.

This ensures that improvement strengthens people as well as processes.

Sustaining the Thinking People System

When leaders drive Jishuken correctly, improvement becomes self-sustaining. Standards are upheld, learning continues, and capability grows generation after generation.

The system no longer depends on tools or programs. It depends on how leaders think and behave.

Conclusion

Inspiring leaders to drive Jishuken completes the Lean TPS learning system. Through participation, reflection, and teaching, leaders transform improvement into a continuous capability-building process.

This is the essence of the Thinking People System: leaders who learn, think scientifically, and develop others through disciplined practice at the Gemba.

16: Lean TPS Basic Training – From Kaizen Thinking to Global Jishuken

Building Shared Thinking and Capability Before Advanced Jishuken Study

Lean TPS Basic Training provides the structured foundation that enables Jishuken to function as a leadership development system. It establishes common thinking, disciplined learning, and shared standards before advanced study occurs. This section explains how Lean TPS Basic Training develops individual capability, connects learning to practice, and prepares people and leaders to participate effectively in Jishuken at every level of the organization.

Figure 16: Lean TPS Basic Training – From Kaizen Thinking to Global Jishuken: Structured learning system showing how foundational TPS training progresses into departmental, plant wide, and global Jishuken capability.

How Structured Lean TPS Basic Training Enables the Progression from Kaizen Thinking to Global Jishuken

Lean TPS Basic Training creates the conditions required for effective improvement. It ensures that participants share a common understanding of TPS principles, problem solving logic, and reflection discipline.

Without this foundation, Jishuken becomes activity rather than learning. With it, Jishuken becomes a method for developing thinking people.

Structured Learning Progression

The training system follows a deliberate sequence that builds capability step by step. Each module introduces a specific aspect of TPS thinking and reinforces it through application and reflection.

Participants learn to observe work, identify abnormality, stabilize processes, and reflect on results. This progression transforms individual learning into team capability and prepares participants for more complex study environments.

Standardization of Learning

Training is standardized and visible. Schedules, participation, and completion are tracked to ensure consistency across departments and shifts.

This standardization reinforces that learning is not optional or informal. It is a managed process with clear expectations and accountability.

Leaders are responsible for confirming that learning occurs and that it is applied in daily work.

From Training to Practice at the Gemba

Lean TPS Basic Training connects classroom learning directly to the Gemba. After each module, participants apply concepts through observation, small improvement activities, and reflection.

This reinforces that TPS is learned through doing, not instruction alone.

Reflection sessions convert experience into understanding and ensure that learning influences behavior and decision making.

Preparing People for Jishuken

Lean TPS Basic Training prepares individuals to participate meaningfully in Jishuken. Participants arrive with a shared language, common problem solving structure, and experience with reflection.

This allows Jishuken studies to focus on deeper system learning rather than basic instruction.

The upward spiral shown in the model illustrates how individual learning expands into departmental, plant wide, and global capability.

A Living Leadership Development System

The training board functions as a living management system. It makes learning visible, tracks progress, and links training participation to leadership behavior.

Leaders are expected to teach what they learn, coach others, and confirm application through observation.

This transforms training into leadership development rather than certification.

Conclusion

Lean TPS Basic Training is the foundation that supports all advanced learning within the Toyota Production System. It develops disciplined thinking, reinforces reflection, and prepares people to sustain improvement independently.