The history of Jishuken begins with Mr. Taiichi Ohno and continues through the generations of Toyota leaders who followed his approach to building capability through structured learning. The timeline of Jishuken is more than a history of projects. It is the record of how Toyota sustained the discipline of improvement by connecting people development to real work.

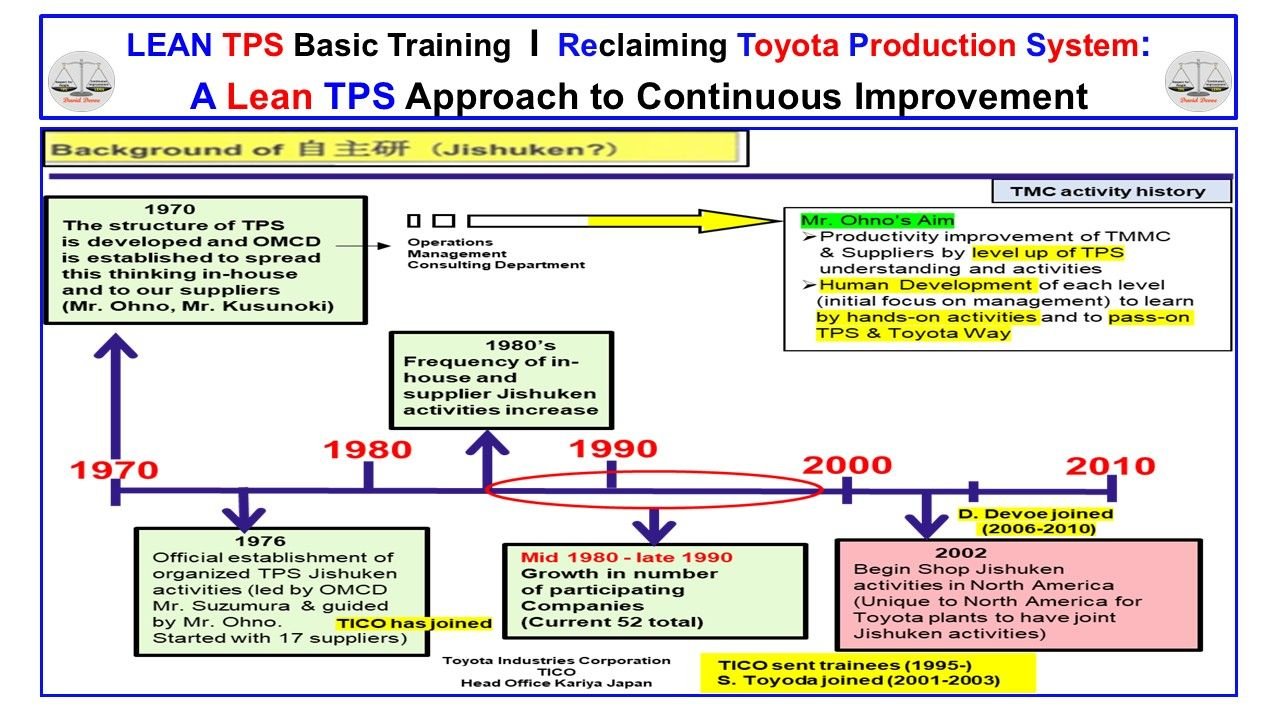

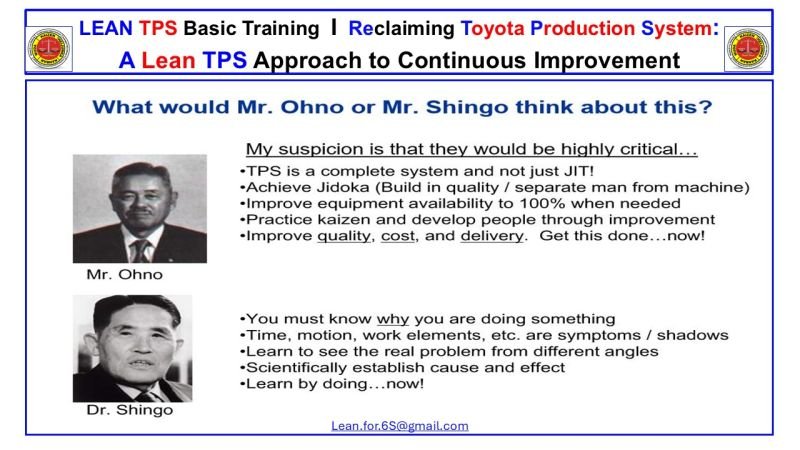

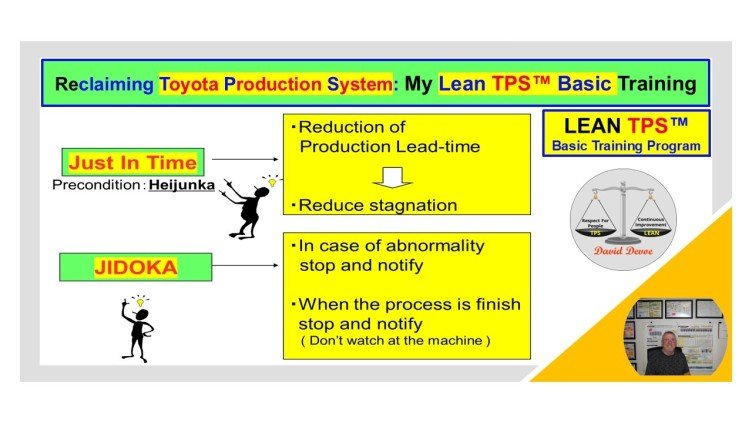

In 1970, the Operations Management Consulting Department (OMCD) was created to formalize and spread the Toyota Production System both inside the company and across its suppliers. Mr. Ohno and Mr. Kusunoki led this initiative with one objective: to make TPS a living system of thinking, not a written system of rules. Learning had to occur through direct activity at the Gemba, not through instruction alone.

By 1976, supplier Jishuken was officially organized under OMCD. Mr. Suzumura, working under the guidance of Mr. Ohno, led the first group of 17 supplier companies. The method was clear and practical. Managers and engineers came together on-site to identify real problems, measure them, and test countermeasures. Every Jishuken event was both a Kaizen study and a leadership development session. Improvement was never separated from human development.

Through the 1980s, Jishuken activities expanded rapidly. In-house and supplier study groups increased in frequency, and more plants began using the approach as a structured way to develop capability. By the late 1990s, more than 50 companies were participating. Toyota Industries Corporation joined these activities in 1995, linking its manufacturing and supplier base to the same improvement philosophy.

In 2001, S. Toyoda joined as a trainee, continuing the direct lineage from Mr. Ohno. That decision symbolized Toyota’s belief that even top management must learn TPS through hands-on experience. Leadership development at Toyota has always been rooted in practice, not theory.

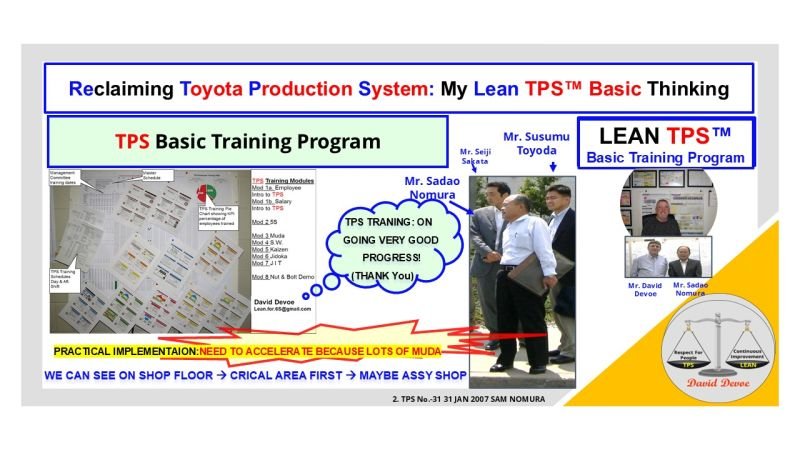

In 2002, Jishuken expanded to North America. This marked a turning point in TPS history. For the first time, Toyota plants outside Japan collaborated in joint Jishuken activities. These were not symbolic exchanges. They were deep, structured learning sessions where teams studied processes, identified waste, and rebuilt systems together. The same principles that guided Ohno’s teams in Japan worked equally well across continents because the foundation was human development through structured improvement.

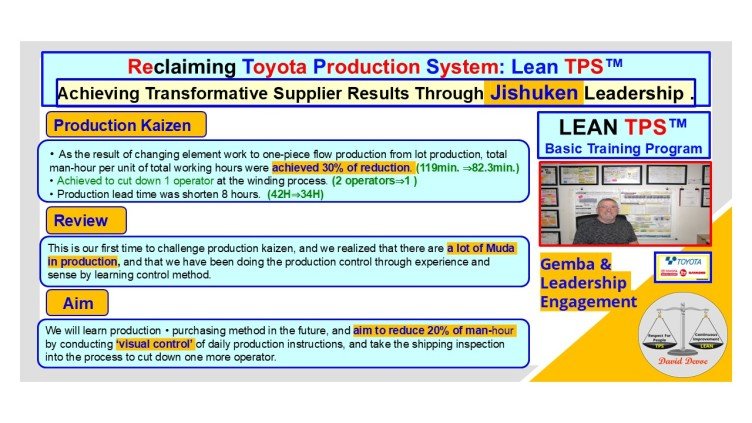

From 2006 to 2010, I had the privilege to participate in Jishuken as part of the Toyota Material Handling TPS Working Group in North America. The focus was clear. Every improvement project was also a development project. Leaders learned by doing. The more problems we solved, the more capability we built. Each activity linked directly to Standardized Work, visualization, and leadership coaching.

In 2010, that structure in Canada came to an end. When the Brantford facility was idled, the Jishuken program stopped as well. Years of development were lost in a moment. The experience taught me a lasting lesson. Systems like Jishuken cannot survive on enthusiasm alone. They depend on structure, leadership commitment, and continuity. When the structure breaks, the learning stops.

That is why Jishuken remains central to how I teach Lean TPS today. The purpose is not only to improve processes but to strengthen people. Jishuken is the purest form of Mr. Ohno’s vision: learning through action, reflection, and teamwork. It is how organizations develop leaders who understand that improvement and respect for people are the same idea expressed through different actions.