Introduction

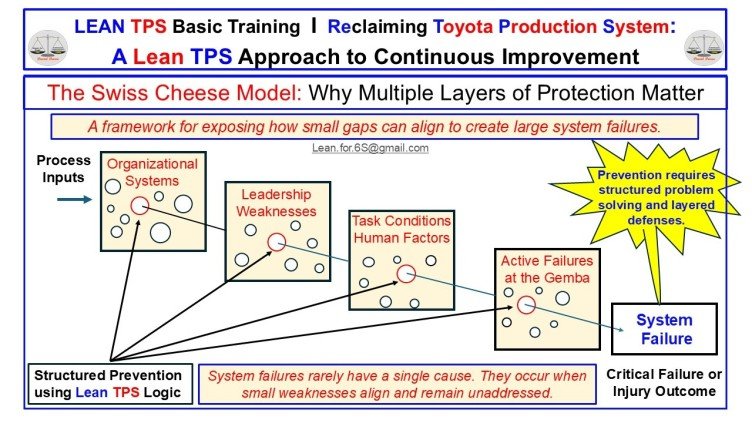

In every organization, problems rarely appear suddenly. They build quietly across weakened systems, unclear leadership routines, and unstable work conditions. When these weaknesses align, the result is failure that seems to come from nowhere.

The Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model™ was created to help leaders see that alignment before it occurs. It is a structured, visual method for understanding and preventing systemic failure.

The model adapts James Reason’s original Swiss Cheese concept (1990) into a Lean TPS format grounded in Toyota Production System principles. It combines visual thinking, leadership discipline, and structured problem solving into a single prevention model.

Executive Summary

Modern organizations face increasing complexity and volatility. In this environment, isolated inspections and after-the-fact analysis are no longer enough. Root causes rarely exist alone. They align silently through small system gaps, weak leadership habits, and inconsistent task conditions.

The Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model reveals this alignment. It transforms risk prevention from a reactive activity into a structured leadership practice. By connecting the principles of Standardized Work, Jidoka, 5S Thinking, and Respect for People, the model provides a way to see failure forming before it reaches the customer, the employee, or the system itself.

1. Origins of the Model

James Reason developed the Swiss Cheese Model in 1990 while studying human error in aviation. He discovered that major accidents were not caused by a single catastrophic mistake. They resulted from the silent alignment of multiple weaknesses across layers of defense.

Each layer in a system was designed to stop an error. Yet every layer contained small holes—representing gaps in process design, training, communication, or leadership. A failure occurred only when those holes lined up.

The insight was simple but profound: to prevent accidents, organizations must strengthen the layers of protection, not just react to visible errors.

The Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model builds on this same logic but applies it through the lens of the Toyota Production System. Instead of analyzing accidents after they happen, it integrates layered protection into the daily management structure.

2. Why Lean TPS Adapts This Model

Inside Toyota, we learned that the purpose of TPS was not only efficiency or cost reduction. It was the creation of systems that reveal problems early, while they are still small and manageable.

Core TPS elements such as Jidoka, Andon, Standardized Work, 5S, and visual management exist to expose instability in real time. Each one forms a barrier that prevents risk from moving downstream.

The Swiss Cheese Model fits naturally with this mindset. It provides a clear visual method to show how weaknesses in systems, leadership, human factors, and frontline execution can silently align if they are not strengthened daily.

By translating Reason’s original theory into a Lean TPS framework, the model becomes a living prevention tool rather than a diagnostic chart. It helps leaders identify which layers are weak, where to intervene, and how to reinforce the system before failure takes shape.

3. The Four Layers of Protection

Each slice in the Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model represents a structured layer of prevention. The strength of the organization depends on how well these layers work together.

1. Organizational Systems

This layer represents the foundation. It includes the design of processes, standards, policies, and flow. Weaknesses in this layer include poor KPIs, unstable standards, missing Standardized Work, and unclear cross-functional coordination.

When this layer drifts, risk begins to form silently within the structure itself.

2. Leadership Weaknesses

Leaders are responsible for stabilizing and verifying the system. When they rely on reports instead of direct observation, or when coaching and follow-up are missing, the layer loses strength.

Leadership weaknesses allow instability to move downstream without detection.

3. Task Conditions and Human Factors

This layer reflects the conditions where people perform daily work. Fatigue, unclear instructions, distractions, and overburden increase the likelihood of error. When the environment forces people to adapt instead of improve, instability becomes normal.

4. Active Failures at the Gemba

The final layer represents visible mistakes at the point of work. By the time an active failure occurs, the previous layers have already allowed risk to pass through.

At this stage, an operator’s error is only the final symptom of a much deeper system problem.

Each of these layers must be deliberately maintained and reinforced. No single layer can protect the organization on its own. The strength of Lean TPS lies in creating a system where problems are surfaced early and corrected at their origin.

4. Example: Healthcare Medication Error

Event: A patient receives the wrong medication dose in a hospital.

- Organizational Systems: Labeling across departments is inconsistent. Medication packaging and barcodes differ between suppliers.

- Leadership Weaknesses: Communication between pharmacy and nursing teams is limited. Leadership meetings focus on reports, not process observation.

- Task Conditions and Human Factors: The medication area is noisy and distracting. Nurses are overburdened during shift change.

- Active Failure at the Gemba: A nurse selects and administers the wrong dose.

The patient harm appears sudden, but it is the outcome of silent alignment across all layers. Each layer contained weaknesses that were never addressed.

5. Example: Aviation Approach Incident

Event: An airplane crash occurs during approach under low visibility conditions.

- Organizational Systems: Outdated approach charts and inadequate updates compromise safety.

- Leadership Weaknesses: Flight training emphasizes regulatory compliance instead of critical thinking and decision-making.

- Task Conditions and Human Factors: Autopilot mode indications are unclear. The cockpit environment is high workload.

- Active Failure at the Gemba: The crew disengages the autopilot incorrectly and loses situational awareness.

Again, the visible error was only the final step in a chain that began far upstream.

6. Applying Structured Problem Solving

The Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model reinforces a critical truth: problems are not caused by individuals, they are caused by systems.

This aligns directly with Jidoka, which builds quality into the process rather than relying on inspection afterward.

The 5 Why method, when combined with the Swiss Cheese Model, helps teams trace each failure back through the layers. Instead of finding one root cause, they identify multiple contributing weaknesses. Each Why becomes a lens to locate a broken layer.

Complementary Tools

The model works effectively with:

- 5 Why Analysis to trace cause alignment.

- Ishikawa (Fishbone) Diagrams to categorize causes across People, Methods, Machines, and Materials.

- Fault Tree Analysis (FTA) to map combinations of small events that create large outcomes.

- FMEA to rank severity, occurrence, and detection of failure modes.

- Event Chain Mapping to show how risks evolve over time.

- Pareto Analysis to prioritize which layers need immediate reinforcement.

Each of these tools supports the Lean TPS goals of visibility, stability, and capability development.

7. Tools That Do Not Fit Lean TPS Logic

Some modern analytic tools, such as Monte Carlo simulations or Bayesian risk models, rely on probabilistic forecasting. While useful in academic or financial contexts, they do not expose risk at the Gemba or strengthen leadership behavior.

Lean TPS does not predict failure; it designs systems to prevent it. Prevention is built through observation, standardization, and reflection, not algorithms.

8. Leadership and Learning

After decades of leading Lean TPS improvement, I have found that most leaders struggle not because they lack data, but because they cannot see how risks form in their own systems.

The Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model gives them that visibility. It helps teams move from reaction to prevention. It turns abstract leadership values into a structured habit of protection.

By teaching people to observe system drift, study real causes, and rebuild layers, organizations strengthen both their processes and their people.

This is not an academic model. It is a practical leadership method for protecting people, stabilizing operations, and sustaining continuous improvement.

9. Conclusion

In a world shaped by volatility and complexity, risk no longer arrives as isolated events. It builds quietly across systems, leadership, tasks, and human factors.

The Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model provides a simple but powerful framework to visualize this alignment. It connects daily work, leadership routines, and organizational learning into one continuous system of prevention.

When applied with discipline, it restores the original intent of the Toyota Production System: to protect people, ensure flow, and strengthen organizations through daily reflection and improvement.

Failures rarely happen from one cause. They occur when small weaknesses align and remain unaddressed.

Lean TPS prevents that alignment through structure, practice, and leadership presence at the Gemba.