At Toyota, the title Sensei carries a special meaning. It is not a title of authority. It is a title of responsibility. A Sensei is a teacher who leads by doing, who preserves the living knowledge of the Toyota Production System through activity and reflection at the Gemba. The Sensei ensures that improvement does not fade with time, that people continue to learn, and that the discipline of problem solving remains part of daily work.

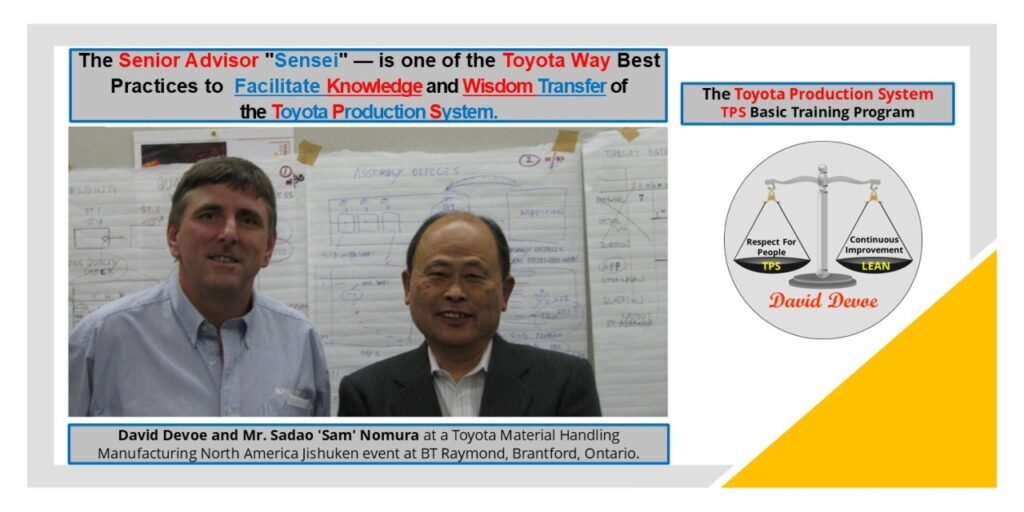

In my own TPS journey, that role was embodied by Mr. Sadao “Sam” Nomura, Senior Advisor for Toyota Industries Corporation. When he visited our BT Raymond facility in Brantford, Ontario, he did not come to give speeches. He came to see reality. He walked the floor, studied the process, and asked questions that revealed what others missed. His visits became turning points in how our leadership team understood quality, flow, and accountability.

The Role of the Sensei in TPS

Within Toyota, a Sensei’s purpose is not to manage results but to develop capability. The Sensei teaches through observation and dialogue, not instruction alone. They help leaders see what their systems are showing them and what they are choosing not to see. When Mr. Nomura arrived, he reminded us that the purpose of improvement was not to meet a target, but to strengthen the people who achieved it. A Sensei develops eyes for waste, ears for problems, and the discipline to act immediately.

He expected leaders to stand at the Gemba and verify facts with their own eyes. “If you have not seen it yourself,” he told us, “you cannot know it.” That lesson became the foundation for our Genchi Genbutsu practice. Every audit, every improvement event, every Jishuken started from that principle. Problems had to be seen firsthand, analyzed through direct data, and solved through structured teamwork.

The Nomura-Grams: Capturing Knowledge in Motion

Mr. Nomura had a simple but powerful teaching method. During his Gemba tours, he carried small slips of paper and wrote short notes in real time. Each observation described one condition, one problem, or one opportunity for improvement. These were not suggestions. They were facts seen through disciplined eyes. By the end of each visit, his desk would be covered with these handwritten slips, which we came to call Nomura-Grams.

At the close of every visit, his notes were transferred onto A3-size sheets. Each A3 preserved the flow of his thinking: observation, cause, countermeasure, and follow-up. They became both a record and a learning tool. One of the most memorable of these was Nomura-Gram #31, created during his Brantford visit. It captured key quality conditions in our production process and recognized the training program I had developed for Lean TPS education. He requested that a copy of those materials be shared with him, not as a compliment, but as a signal that the learning structure should continue after his departure. That request remains one of the greatest honors of my career.

Mentorship Through Activity and Reflection

Nomura taught that mentorship was not discussion, it was activity. He expected leaders to experiment, measure, and reflect. Every countermeasure had to be confirmed by data, every improvement had to show a measurable effect, and every problem had to be followed to its root cause. He taught that true learning comes from reflection on experience, not from instruction alone. His favorite method was to return to the same area weeks later and quietly ask, “What has changed?” If we could not show progress, it meant we had not learned.

He pushed our leaders to document what they saw and to connect every observation to Standardized Work. He said, “If the work is not written and visible, the learning cannot spread.” That thinking shaped how we built our early Standardized Work Audits and our approach to visual management. It was not about control, but about creating a shared language that made the condition of the process visible to everyone.

The Sensei as the Living Standard

In many organizations, the word “standard” is associated with documents or compliance. Nomura showed that the true standard is the behavior of the leader. He expected consistency of observation, consistency of response, and consistency of respect. He believed that every Sensei must live the system they teach. When a Sensei corrects a problem, it is not a critique of the person, but a reinforcement of the standard. Through that discipline, the organization learns to see deviation not as failure, but as an opportunity to grow capability.

Nomura’s mentoring style reflected the essence of the Toyota Way. His teaching combined respect for people with the continuous improvement mindset. When he guided a team, he never imposed solutions. He asked questions that guided us to discover the cause for ourselves. The lesson was clear: improvement owned by the learner will endure; improvement imposed from outside will fade.

Knowledge Transfer as the Foundation of TPS

TPS survives because of structured knowledge transfer. At Toyota, every method, chart, and process has meaning because someone took the time to teach it properly. Nomura reminded us that this is what separates a living system from a mechanical one. He said, “If the people cannot explain the reason for the standard, you have not taught them.” His focus on education through experience shaped how I later designed Lean TPS Basic Training. The goal was never awareness. The goal was capability.

The Nomura-Grams and A3s became our living textbooks. They were simple, visual, and factual. They captured not only what was done, but how it was thought through. They were not filed away. They were displayed and studied. Teams reviewed them during reflection sessions, learning to trace the cause-and-effect relationships in their own work. In this way, Nomura ensured that knowledge would remain active long after his visits ended.

Leadership Development Through Jishuken

Nomura believed that Jishuken was the highest expression of learning in TPS. It was leadership development through study and improvement. When he joined a Jishuken event, he reminded participants that the goal was not cost reduction or efficiency. The goal was to develop leaders who could see variation, test countermeasures, and teach others. His presence at BT Raymond reinforced this principle. Each week of Jishuken concluded with a reflection session, where leaders explained what they saw, what they learned, and what they would do differently. Nomura’s questions were short, but they always went to the root. “Why did you choose that countermeasure?” “What did the data tell you?” “How will you prevent recurrence?” He taught us that a good answer is not one that sounds convincing, but one that is proven by facts.

The Legacy of the Sensei

When I reflect on those experiences, I realize that Nomura’s true lesson was not about tools or results. It was about stewardship. A Sensei does not own the system. They protect it by ensuring others understand it. The strength of TPS lies in its ability to regenerate itself through people who have been taught to think and act with purpose.

Mr. Nomura’s mentorship remains the model I follow today. His Nomura-Grams still guide how I observe, record, and teach. They remind me that the purpose of improvement is not perfection, but learning. Each problem is a lesson waiting to be discovered. Each improvement is proof that people are growing. Through that discipline, TPS continues to evolve, and the respect for people that defines Toyota continues to strengthen.

That is the legacy of the Senior TPS Advisor. Not a title, but a responsibility to pass forward the wisdom, structure, and humility that make continuous improvement possible.