Executive Abstract

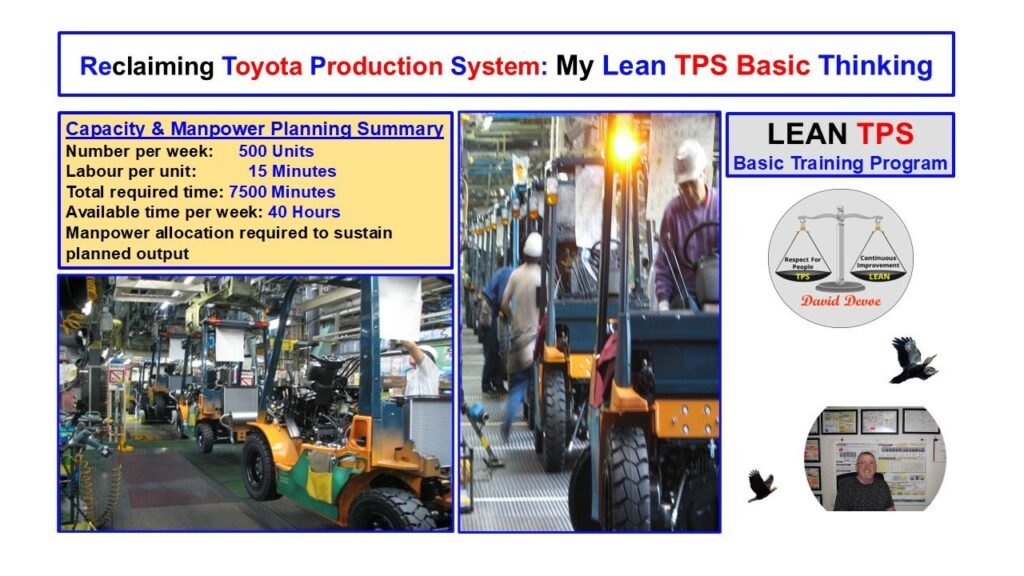

Manpower and capacity planning inside the Toyota Production System are not administrative calculations or scheduling exercises. They are leadership governance mechanisms that determine whether work is permitted to begin under conditions that protect Quality, people, and system stability. This article examines how Toyota uses simple arithmetic not to optimize output, but to expose risk, challenge assumptions, and assign leadership responsibility before execution begins. The example shows that identical calculations can either govern conditions or merely justify decisions already made, depending on when assumptions are tested and who owns the consequences.

Through a structured walk from demand confirmation to daily governance at the gemba, this article demonstrates how Toyota defines capacity as a proven condition rather than a theoretical entitlement. Manpower decisions, utilization assumptions, efficiency claims, margin, balance, and sensitivity testing are treated as Quality controls rather than performance targets. The result is a system that prevents overburden and conflict before they form, rather than explaining loss after it occurs. Manpower and capacity planning therefore become one of the clearest indicators of Toyota Production System maturity: not because the math is complex, but because the governance discipline required to use it correctly is rare.Top of Form

The Situation on the Floor

The assembly line is expected to produce five hundred forklifts per week. Customer demand is confirmed. The product mix is stable. Standard work exists. Nothing in the plan signals urgency or danger. Most organizations interpret this combination as a low-risk condition.

Experience inside Toyota teaches the opposite lesson. Stable demand combined with established standard work creates the highest exposure point in the system. Confidence replaces scrutiny at precisely the moment when leadership judgment matters most.

At Toyota BT Raymond, similar conditions often preceded the most serious Quality problems I observed. Schedules looked clean. Volumes matched historical performance. Headcount aligned with prior weeks. Managers believed the system was proven because it had produced similar numbers before. That belief became the risk.

Production systems fail most often when leaders assume yesterday’s stability guarantees today’s capability. Past success hides current drift. Small changes in manpower availability, method adherence, material timing, or support response accumulate quietly. Paper plans do not reveal those changes. The floor reveals them immediately.

In many plants, this moment triggers a familiar routine. Planning confirms the weekly volume. Staffing levels are compared against a spreadsheet. A headcount number receives approval. Production starts. Leadership attention shifts forward to output tracking and issue response. Responsibility for results moves downstream before work begins.

Toyota does not treat the start of production as execution. Toyota treats the moment before production as a Quality gate.

Before the first unit is built, leadership must decide whether the conditions under which work will be performed can sustain normal operations without overburden, shortcuts, or silent compensation. That decision determines whether Quality will be protected or consumed later through effort.

At Toyota, leaders never asked whether five hundred units could be built. Leaders asked whether five hundred units could be built repeatedly, predictably, and without requiring people to solve design problems through personal strain.

Manpower availability, method stability, support response, and time margin were examined together. Each factor represented a condition, not a variable. Each condition either protected Quality or eroded it before defects appeared.

One planning review in particular remains clear. Demand had not changed. The product had not changed. Standard work had not changed. A single experienced team leader was scheduled for vacation. No replacement with equivalent capability was available. The schedule still showed green. Leadership stopped the discussion and reset the plan.

Production did not begin until coverage and support conditions were corrected. Output loss never occurred. Quality loss never occurred. No report later explained the absence of problems. Prevention left no data trail.

Most organizations treat manpower planning as arithmetic. Toyota treats manpower planning as governance.

Scheduling exercises answer how many units to build. Governance decisions answer whether the system deserves permission to run. That distinction defines Toyota Production System maturity.

Risk does not live in demand volatility alone. Risk lives in unexamined assumptions about people, time, and support. Stable conditions remove the excuse to ignore those assumptions. Mature leaders use stability to expose reality rather than to justify complacency.

The moment when everything appears normal is the last opportunity to prevent failure rather than manage it.

Manpower and Capacity Planning as a Measure of Toyota Production System Maturity

Manpower and capacity planning inside the Toyota Production System function as leadership governance mechanisms, not as administrative calculations. These decisions exist to protect Quality, prevent overburden, and stabilize work before production begins. The purpose is prevention, not efficiency optimization.

Most organizations describe manpower planning as a support activity. Toyota treats manpower planning as a leadership obligation. Headcount decisions establish the conditions under which people will be asked to perform work. Those conditions determine whether standards can be followed, whether abnormalities will surface early, and whether Quality will be protected without heroic effort.

Experience inside Toyota confirms that manpower planning failures rarely appear as planning failures. Failures appear later as execution problems, absenteeism, overtime, missed delivery, or Quality escapes. The original decision that permitted those outcomes often receives no attention because the decision occurred before visible results existed.

Toyota leaders understand that work begins long before the first unit moves down the line. Work begins when leadership defines whether demand, time, people, and support can coexist without forcing tradeoffs. That definition happens during manpower and capacity planning.

The Toyota Production System does not treat capacity as an inherent property of equipment or lines. Capacity exists only when people can perform standardized work repeatedly within defined time boundaries. Equipment does not produce forklifts. Systems of people, methods, materials, and support produce forklifts.

During my time at Toyota, manpower discussions always surfaced before production discussions. Leaders asked whether available people could perform the work as designed, whether support functions could respond within expected time, and whether margin existed to absorb normal variation. Leaders did not wait for problems to reveal missing capacity. Leaders governed capacity before problems were allowed to occur.

The planning example used in this article serves as a teaching story, not as a formula lesson. The calculations themselves remain simple. The thinking behind the calculations reveals maturity.

Early-stage systems use numbers to justify decisions already made. Mature Toyota systems use numbers to challenge assumptions before decisions are permitted. The same arithmetic produces very different outcomes depending on who owns the assumptions and when those assumptions are tested.

The numbers matter because they expose reality. The numbers do not matter as targets, performance claims, or optimization tools. Toyota never treated manpower calculations as proof of success. Toyota treated manpower calculations as a mechanism for discovering whether leadership was prepared to accept responsibility for system conditions.

Governing conditions before work begins separates Toyota Production System maturity from reactive management. Leaders who govern conditions accept accountability for Quality outcomes that never appear. Leaders who delegate condition-setting inherit problems that require explanation later.

Reactive organizations learn from failure. Toyota learns before failure is allowed to occur. Manpower and capacity planning form one of the last upstream points where that learning can protect people and Quality at the same time.

This teaching example exists to make that distinction unavoidable. Once the difference between governing conditions and reacting to outcomes becomes visible, maturity can no longer be measured by output alone. Maturity becomes visible in the decisions leaders make before production is allowed to start.

The Situation on the Floor

An assembly line is expected to produce five hundred forklifts per week. Demand is known. The product remains stable. Work content has been defined and documented. Standardized work exists. Most indicators suggest normal conditions.

Uncertainty still exists, even when every planning input appears confirmed. The uncertainty does not concern volume or sequence. The uncertainty concerns whether the system, as it will actually operate, can meet demand without creating strain, instability, or downstream Quality risk.

Many organizations interpret this moment as a scheduling checkpoint. A calculation converts demand into headcount. Approval is granted. Production begins. Leadership attention moves forward to delivery tracking and issue escalation. The decision is treated as complete once numbers align.

Toyota treats the same moment as the first Quality decision of the production cycle.

Manpower planning inside Toyota establishes whether work can be performed normally. Normal does not mean fast. Normal means repeatable, predictable, and executable without requiring people to compensate for system weakness. Leadership responsibility begins before the first unit moves because Quality protection cannot be recovered once overburden is introduced.

During my time working inside Toyota production environments, leaders consistently slowed discussions at this point. Even when demand and staffing matched historical patterns, leaders challenged whether current conditions still deserved permission to run. Experience taught that yesterday’s balance rarely survived unchanged into the next cycle.

Conditions drift quietly. Absenteeism patterns change. Support response degrades. Material presentation evolves. Small deviations accumulate without appearing in planning tools. The floor experiences those deviations immediately. Schedules do not.

Toyota leaders therefore asked different questions. Leaders asked whether every process could be performed within standard time without rushing. Leaders asked whether relief coverage existed for predictable absences. Leaders asked whether team leaders could support problem response without abandoning their roles. Leaders verified whether margin existed to absorb minor disruption without forcing shortcuts.

These questions were not symbolic. Production was delayed when answers were unclear. Output targets did not override uncertainty about conditions. Leadership credibility rested on preventing instability, not on explaining results later.

Many organizations believe Quality risk appears after production begins. Toyota treats Quality risk as something created or prevented before production starts. Manpower planning becomes the earliest opportunity to decide whether the system will operate under control or under stress.

Scheduling exercises answer how many units should be built. Governance decisions answer whether building those units will consume people, standards, or Quality in the process. Toyota separates those decisions deliberately.

The moment before production begins defines whether leaders are governing work or reacting to work. Once production starts, options narrow. Once overburden appears, recovery always costs more than prevention.

This moment on the floor determines whether leadership accepts responsibility for conditions or transfers responsibility to execution. Toyota maturity becomes visible at this exact point.

Why Toyota Treats Manpower as a Quality System

Manpower planning in the Toyota Production System exists to prevent failure, not to maximize output. Too few people create overburden that forces shortcuts and erodes standards. Too many people mask instability by absorbing problems through excess capacity. Both conditions damage Quality because both prevent abnormality from being seen and corrected.

Toyota defines Quality as the ability to perform work as intended under normal conditions. Quality protection begins before defects exist. Quality protection begins when work can be performed repeatedly, predictably, and without extraordinary effort. Manpower planning establishes whether those conditions can exist at all.

Inspection does not protect Quality inside Toyota. Reaction does not protect Quality inside Toyota. System design protects Quality. Manpower decisions shape that design more directly than most leaders realize.

Experience inside Toyota production environments made this relationship unavoidable. Lines with generous staffing often appeared calm while hiding unresolved instability. Problems disappeared into buffers. Standards drifted quietly. Leaders received reassuring reports while capability eroded. Lines with marginal staffing showed stress immediately. Abnormality surfaced early. Leaders were forced to confront system weaknesses before Quality escaped.

Toyota never treated either condition as acceptable. Overburden harmed people and Quality. Excess manpower delayed learning and concealed risk. Leadership responsibility existed to establish balance, not to choose between extremes.

Manpower planning therefore carried governance weight. Headcount approval represented permission for work to occur under defined conditions. Leaders understood that approving headcount without validating conditions transferred risk downstream to operators, team leaders, and customers.

At Toyota, manpower discussions never ended with a number alone. Leaders examined whether the approved staffing level allowed standardized work to be followed without acceleration. Leaders examined whether support functions could respond within takt time expectations. Leaders examined whether team leaders retained capacity to perform their leadership role rather than serve as emergency labor.

Leadership did not treat manpower as a variable cost to be optimized. Leadership treated manpower as a finite human capability that required protection. Overburden consumed that capability. Excess hid its degradation. Quality suffered in both cases.

Governance required leaders to decide how much variation the system could absorb without forcing compensation. Margin existed for protection, not for comfort. Removing margin to chase output created fragile systems. Adding margin without purpose delayed problem exposure.

Toyota maturity appeared in how leaders held that balance. Mature leaders accepted slower ramp-up, delayed starts, or adjusted plans when manpower conditions could not protect Quality. Immature leaders approved numbers and waited for results.

Manpower planning inside TPS therefore functioned as a Quality system. The decision defined whether work would be governed or whether execution would be forced to compensate. Leadership ownership of that decision determined whether Quality remained protected or became an outcome to be explained later.

Defining the Problem Is a Governance Act

The assembly line must produce five hundred units per week. Each unit requires fifteen minutes of direct assembly work. Each assembler is scheduled for forty hours per week. Utilization is assumed at eighty percent. Efficiency is assumed at one hundred ten percent. Many organizations treat these values as technical inputs required to complete a calculation.

Toyota treats each value as a leadership assumption that carries Quality risk.

Demand must be credible, not aspirational. Credibility requires confirmation that customer orders represent firm commitment rather than forecast optimism. Leaders at Toyota verified demand stability before permitting downstream decisions to proceed. Uncertain demand invalidated every calculation that followed.

Standard time must reflect reality on the floor, not engineering intent or historical averages. Toyota leaders verified standard time through direct observation. Work elements were confirmed under normal conditions, not during ideal demonstrations. Inflated standards transferred risk directly to people.

Utilization assumptions exposed system stability. Breaks, meetings, material delays, tool issues, and problem response consumed time every day. Toyota leaders required utilization assumptions to reflect known interruptions rather than hoped-for availability. Ignoring known losses converted planning optimism into operational strain.

Efficiency assumptions required earned capability. Efficiency above one hundred percent existed only after stable methods, trained people, and reliable support were proven. Toyota never treated efficiency as a planning entitlement. Efficiency without stability represented future overburden disguised as productivity.

Experience inside Toyota made the danger of unchallenged assumptions clear. Planning reviews often paused when leaders encountered optimistic utilization or efficiency figures. Leaders asked how those numbers had been achieved historically and under what conditions. Leaders rejected assumptions that relied on pace increases, skipped steps, or informal heroics.

Every assumption embedded a choice. Accepting optimistic assumptions shifted responsibility downward. Challenging assumptions kept responsibility with leadership. Governance lived in that choice.

Defining the problem correctly required more than selecting numbers. Defining the problem required deciding which risks leadership was willing to accept and which risks leadership would eliminate before work began. Numbers served as a language for that decision, not as proof of correctness.

Low-maturity systems accepted assumptions to keep plans moving. Mature Toyota systems challenged assumptions to prevent failure. The math remained simple. Ownership changed completely.

Problem definition therefore functioned as a governance act. Leaders either governed conditions by validating assumptions or delegated risk by accepting them. Quality outcomes later reflected that choice with perfect consistency.

Defining the problem correctly represented the first visible test of Toyota Production System maturity.

Making Work Visible Through Time

Toyota converts work into time to make reality visible. Time serves as the common language that connects demand, people, methods, and leadership decisions. Units, schedules, and headcount obscure strain. Time exposes it.

Five hundred units multiplied by fifteen minutes results in seven thousand five hundred minutes of total direct labor required per week. Converted to hours, the system requires one hundred twenty five hours of direct work. The calculation itself remains simple. The meaning of the calculation carries governance weight.

Accounting uses time to report what already happened. Toyota uses time to reveal whether work can happen normally. Expressing work as time forces leaders to confront whether demand and capacity coexist or conflict before production begins.

Experience inside Toyota made the power of this conversion unmistakable. Planning meetings that stayed in units and headcount moved quickly and ended comfortably. Planning meetings that converted work into minutes slowed immediately. Leaders began to ask different questions once time replaced abstraction.

Time exposes accumulation. Small inefficiencies that appear harmless at the task level compound rapidly when multiplied across volume. A thirty second deviation repeated five hundred times consumes more than four hours of labor in a week. Schedules do not show that loss. Time calculations make the loss unavoidable.

Time also exposes fragility. Systems that appear balanced in aggregate often collapse when examined minute by minute. Tight alignments leave no margin for response. Leaders at Toyota used time visibility to decide whether margin existed to protect Quality or whether people would be forced to compensate.

Work expressed abstractly allows optimism to survive unchallenged. Work expressed in time removes optimism from the discussion. Leaders either see alignment or see conflict. No explanation can hide the result.

During my time supporting Toyota planning reviews, leaders repeatedly returned discussions to time when debates drifted toward justification. Questions about performance, effort, or commitment ended once time revealed mismatch. Decisions followed exposure rather than persuasion.

Time therefore functioned as a governance tool. Leaders did not argue about intent once time showed incompatibility. Leaders either changed conditions or delayed production. Quality protection followed that discipline.

Systems that avoid time-based visibility remain dependent on downstream heroics. Systems that expose work through time govern conditions upstream. Toyota Production System maturity becomes visible in whether leaders choose exposure over comfort.

When work remains abstract, imbalance remains invisible. When work is expressed as time, leadership responsibility becomes unavoidable.

Utilization and Efficiency Reveal System Health

Each assembler is scheduled for forty hours per week. Not all of that time becomes available for direct work. Breaks, meetings, material shortages, tool issues, and problem response consume time every day. Utilization reflects how stable the system actually is, not how committed people appear.

Efficiency reflects how well methods function under normal conditions. Stable methods allow work to be performed consistently within standard time. Unstable methods force variation, adjustment, and compensation. Efficiency rises only after stability exists. Efficiency assumed in advance signals optimism rather than capability.

Multiplying scheduled time by utilization and efficiency produces an effective available time of thirty five point two hours per assembler per week. The arithmetic remains simple. The interpretation determines whether leadership governs the system or misreads it.

Utilization and efficiency do not describe people. Utilization describes how often the system interrupts work. Efficiency describes whether the system allows people to perform work as designed. Low utilization signals instability in materials, information, support, or sequencing. Inflated efficiency assumptions hide those same problems by transferring responsibility to pace and effort.

Experience inside Toyota revealed consistent misuse of these measures outside mature systems. Leaders treated utilization as an attendance issue. Leaders treated efficiency as a target. Both interpretations misplaced responsibility and masked root causes.

Toyota leaders never asked why people failed to achieve planned utilization. Leaders asked which system conditions consumed time that should have been available for work. Material delays, unclear instructions, missing tools, and delayed problem response appeared repeatedly once utilization was examined honestly.

Efficiency received equal scrutiny. Efficiency above one hundred percent required proven stability, not ambition. Leaders demanded evidence that methods allowed faster execution without added strain. Efficiency achieved through rushing, skipped confirmation, or informal workarounds was rejected as false improvement.

During planning reviews, Toyota leaders challenged efficiency assumptions more aggressively than demand assumptions. Leaders understood that efficiency optimism forced overburden long before defects appeared. Efficiency optimism converted design failure into execution pressure.

Utilization and efficiency therefore served as diagnostic indicators. Both numbers pointed directly toward system health or system weakness. Neither number justified performance evaluation or personal judgment.

Leadership ownership remained explicit. Low utilization demanded leadership correction of conditions. Efficiency shortfalls demanded method improvement, not exhortation. Accepting either number without investigation transferred Quality risk downstream.

Mature TPS thinking treated utilization and efficiency as mirrors. The numbers reflected leadership decisions already made about system design, support, and stability. Leaders who disliked the reflection were required to change the system rather than reinterpret the image.

Utilization and efficiency revealed whether the system deserved permission to run. Toyota maturity became visible in whether leaders used these measures to govern conditions or to rationalize outcomes.

Determining Manpower Without Creating Overburden

Dividing total required hours by effective available hours results in a requirement of three point five five assemblers. Many organizations treat that result as an inconvenience that must be corrected downward. Toyota treats the result as a warning that conditions leave no margin for stability.

Toyota never assigns fractional people. The number is rounded up to four. Rounding up does not represent inefficiency. Rounding up represents intent to protect Quality and people at the same time.

Margin absorbs variation. Variation exists in every production system. Absenteeism, small delays, minor quality checks, and support response consume time unpredictably. Margin prevents those normal variations from forcing shortcuts or pace increases.

Experience inside Toyota reinforced the importance of deliberate margin. Lines staffed exactly to calculated demand required constant adjustment. Team leaders became emergency labor. Standards eroded quietly. People compensated without signaling abnormality. Reports remained clean while capability degraded.

Lines staffed with intentional margin behaved differently. Small disruptions surfaced immediately. Leaders could respond without rushing work. Team leaders retained time to support, coach, and correct problems. Quality issues appeared early rather than after shipment.

Early-stage thinking minimizes headcount because cost reduction appears tangible and immediate. Capacity risk remains abstract until consequences appear later. Mature TPS thinking governs capacity because leadership understands that cost avoided today often returns as Quality loss tomorrow.

Four assemblers are assigned not to increase output but to stabilize conditions. Stabilization allows standards to be followed. Stabilization allows abnormality to be seen. Stabilization protects people from being used as buffers.

Leadership responsibility appears clearly at this point. Approving three assemblers would require confidence that variation does not exist. Approving four assemblers acknowledges reality and governs it. Toyota leaders consistently chose reality.

During manpower reviews, leaders examined whether margin aligned with known risks. Leaders adjusted plans when margin disappeared due to vacations, training, or support gaps. Output targets did not override protection logic.

Manpower determination therefore became a Quality decision rather than a staffing decision. Leaders who governed capacity prevented overburden before work began. Leaders who minimized headcount created systems that demanded compensation later.

Toyota Production System maturity appeared in whether leaders chose margin as protection or rejected margin as waste. Quality outcomes always followed that choice.

Verifying Capacity Before Problems Appear

With four assemblers scheduled for forty hours each, the line has one hundred sixty scheduled hours available for the week. Applying utilization and efficiency reduces that figure to one hundred forty point eight effective hours. Capacity verification begins only after reality replaces entitlement.

Converted to minutes, the system can support eight thousand four hundred forty eight minutes of work. Dividing available minutes by fifteen minutes per unit yields a weekly capacity of five hundred sixty three units. Capacity now exists as a proven condition rather than an assumed outcome.

Toyota leaders treated this calculation as a permission check. Permission to run existed only when capacity exceeded demand under realistic assumptions. Meeting demand exactly did not satisfy the condition. Exceeding demand created protection.

Excess capacity served a specific purpose. Small stoppages occurred every day. Absenteeism appeared without warning. Minor quality checks consumed time unpredictably. Support response varied by situation. Excess capacity absorbed these variations without forcing people to rush or bypass standards.

Experience inside Toyota demonstrated that systems without verified excess capacity behaved predictably. Pace increased quietly. Breaks shortened informally. Confirmation steps eroded. Abnormality disappeared into effort. Leaders discovered problems only after Quality escaped.

Systems with verified capacity behaved differently. Small problems surfaced immediately because no one needed to hide them. Team leaders responded without abandoning their role. Leaders adjusted conditions rather than explain misses. Quality protection occurred upstream.

Toyota never labeled excess capacity as waste. Waste appeared only when capacity existed without purpose or governance. Capacity created deliberately to protect Quality represented leadership intent, not inefficiency.

Capacity verification occurred before production began because timing mattered. Problems discovered during production demanded reaction. Problems prevented before production demanded governance. Toyota leaders valued prevention because prevention protected people and customers simultaneously.

During planning reviews, leaders repeatedly asked whether calculated capacity reflected reality on the floor. Leaders verified assumptions through observation. Leaders delayed starts when verification remained incomplete. Output pressure did not override uncertainty about protection.

Capacity verification therefore marked a maturity boundary. Immature systems trusted calculations and waited for results. Mature Toyota systems verified capacity and prevented results from becoming explanations.

Toyota Production System maturity became visible in whether leaders required proof of protection before authorizing work. Systems that demanded proof prevented failure. Systems that relied on reaction accepted failure as inevitable.

Learning Through Sensitivity, Not Guesswork

Toyota Production System maturity becomes visible through what leaders choose to test before work begins. Mature leaders test fragility. Immature leaders test optimism.

Reducing efficiency from one hundred ten percent to one hundred percent lowers weekly capacity to five hundred twelve units. Demand remains technically achievable, but margin nearly disappears. Protection weakens. Further reducing utilization to seventy percent drops capacity below demand. The system now requires compensation to meet commitments.

The calculation matters less than the signal it produces. Sensitivity testing reveals which assumptions carry the greatest risk. Efficiency reduction reduces comfort. Utilization reduction removes protection entirely. Leadership attention must follow that signal.

Experience inside Toyota showed that leaders who skipped sensitivity testing learned only after failure occurred. Leaders who tested assumptions learned where governance mattered most. Sensitivity testing replaced debate with clarity.

Toyota leaders treated sensitivity analysis as a learning mechanism, not as a planning artifact. Leaders intentionally stressed assumptions to discover where instability would first appear. Leaders did not ask whether the plan looked acceptable. Leaders asked which condition would fail first under normal variation.

Utilization loss consistently emerged as the dominant risk. Material delays, unclear sequencing, late support response, and method instability consumed time faster than efficiency shortfalls. Pushing people could not recover lost utilization without damaging Quality. Stabilizing conditions could.

During planning reviews, leaders often paused discussions once sensitivity results appeared. Attention shifted away from output targets and toward system correction. Leaders redirected effort toward material readiness, support coverage, method confirmation, and problem response capability.

Sensitivity testing therefore guided governance. Leaders learned where to intervene before work began. Leaders discovered which conditions demanded protection and which assumptions required correction. Guesswork disappeared once sensitivity replaced hope.

Systems that avoided sensitivity testing relied on reaction. Systems that embraced sensitivity governed proactively. Toyota Production System maturity appeared in whether leaders chose to learn before failure or explain failure afterward.

Sensitivity testing taught leaders where governance mattered most. Leaders who learned from sensitivity protected Quality without increasing pressure. Leaders who ignored sensitivity transferred risk to people and accepted instability as normal.

Translating Numbers Into Balanced Work

Once manpower has been confirmed, leadership responsibility shifts from capacity verification to work design. Capacity without balance creates a different form of instability. Balanced work ensures that approved conditions can actually be sustained on the floor.

Available time divided by required units results in a takt time of four point eight minutes per unit. Takt time establishes the rhythm the system must follow to meet demand without acceleration or delay. Takt does not represent a target pace. Takt represents the boundary within which work must fit to remain stable.

Each assembler’s work must align with that rhythm. Element work exceeding takt creates imbalance. Imbalance appears immediately as waiting, rushing, handoffs, or defects. People do not create imbalance. Work design creates imbalance.

Toyota leaders treated imbalance as a governance signal rather than a performance problem. Excessive work content at a station indicated that earlier decisions failed to protect conditions. Leaders responded by redesigning work, adjusting allocation, or revisiting assumptions. Leaders did not ask people to move faster.

Experience inside Toyota reinforced that imbalance exposed truth quickly. Yamazumi charts made unevenness unavoidable. Bars extending beyond takt eliminated debate. Leaders could not explain away imbalance once work content became visible.

Standardized work combination tables served the same purpose. Time, motion, and machine interaction appeared together. Leaders could see where waiting occurred, where overlap created conflict, and where confirmation steps were being compressed. Visibility created obligation.

These tools were never treated as analytical exercises completed by specialists. Toyota treated them as governance devices owned by leaders. Leaders used the visuals to decide whether work deserved approval under current conditions.

Balanced work protected Quality by preventing compensation. Unbalanced work forced people to absorb mismatch through effort. Effort masked abnormality. Masked abnormality delayed learning. Toyota rejected that path deliberately.

During line preparation and change reviews, leaders stood at the boards and asked whether work aligned with takt under normal conditions. Leaders required evidence that balance could be maintained throughout the shift. Approval depended on alignment, not intent.

Balanced work therefore represented the operational proof that manpower and capacity decisions had integrity. Numbers alone did not authorize production. Balanced execution confirmed that conditions governed earlier could exist in reality.

Toyota Production System maturity became visible once numbers translated into stable work without pressure. Systems that achieved numerical balance but failed operational balance revealed shallow thinking. Systems that aligned both demonstrated governance in action.

Where Governance Actually Operates

L

Planning matters only when leadership reviews conditions daily. Plans that remain static documents lose authority the moment reality shifts. Governance requires continuous confirmation that conditions remain valid.

Toyota leaders display capacity, takt, and performance visually at the line because governance must occur where work happens. Visuals exist to expose deviation from normal, not to report results after the fact. Normal conditions are defined explicitly. Abnormal conditions become immediately visible.

Visibility creates obligation. Obligation creates response. Leaders do not wait for weekly summaries to intervene. Leaders respond when conditions drift because delay converts prevention into reaction.

Experience inside Toyota showed that spreadsheets never governed work. Governance occurred during daily confirmation at the gemba. Leaders stood where work was performed and verified whether time, balance, and support matched the plan. Deviations demanded action, not explanation.

Utilization drops signaled instability. Leaders investigated material flow, support response, and method adherence. Leaders did not ask people to work harder. Leaders corrected the conditions that consumed time.

Efficiency assumptions required continuous validation. Stable methods supported efficiency. Drift in methods invalidated efficiency assumptions immediately. Leaders verified whether changes in sequence, tools, or workload had altered reality. Adjustments occurred before output suffered.

Daily governance protected people from absorbing system failure. Team leaders retained time to lead rather than compensate. Operators retained the ability to signal abnormality without fear. Quality protection remained upstream because leadership stayed present.

Organizations that governed through reports reacted late. Deviations appeared after damage occurred. Explanations replaced prevention. Toyota rejected that model deliberately.

Governance lived in daily confirmation because conditions changed daily. Leadership responsibility did not end when planning concluded. Leadership responsibility began when production started.

Toyota Production System maturity appeared in whether leaders governed work through presence, confirmation, and response. Systems governed from spreadsheets relied on hope. Systems governed at the line relied on evidence.

This is where TPS maturity lives.

Improving Methods Without Increasing Pressure

Toyota pursues improvement only after stability exists. Improvement without stability converts learning into pressure. Stability creates the conditions where improvement strengthens the system rather than consuming it.

Reducing assembly time from fifteen minutes to fourteen minutes lowers total weekly labor to one hundred sixteen point seven hours. The same four assemblers now create additional margin. Productivity improves without overtime, pressure, or headcount reduction. Improvement produces protection rather than strain.

Experience inside Toyota reinforced this sequencing relentlessly. Leaders rejected improvement proposals when methods remained unstable. Faster work achieved through rushing, skipping confirmation, or informal coordination received no approval. Leaders required evidence that method changes reduced effort and variation simultaneously.

Method improvement inside TPS targets waste embedded in work design, not effort embedded in people. Improved methods remove unnecessary motion, waiting, and rehandling. Improved methods simplify sequencing and confirmation. Improved methods make normal work easier to perform, not harder to sustain.

Toyota leaders verified improvement through observation. Leaders confirmed that revised methods could be performed repeatedly within takt without acceleration. Leaders confirmed that support response remained adequate. Leaders confirmed that Quality checks remained intact. Approval depended on protection, not on numerical gain.

Margin created through improvement served a defined purpose. Margin absorbed variation. Margin created time for problem response. Margin protected training and skill development. Margin allowed learning to occur without disrupting flow.

Organizations that pursued improvement before stability experienced predictable outcomes. Productivity gains appeared briefly. Overburden increased quietly. Standards eroded. Quality issues surfaced later. Leaders responded with retraining or enforcement. Improvement became another source of instability.

Toyota avoided that trap by treating governance as the prerequisite. Governance stabilized conditions. Improvement then strengthened those conditions. Sequence mattered more than speed.

During Kaizen activities I supported at Toyota, leaders repeatedly stopped teams from implementing attractive ideas prematurely. Leaders asked whether current instability had been addressed. Leaders delayed changes until conditions deserved improvement. Learning occurred without pressure because protection existed first.

Improvement followed governance. Improvement never replaced governance. Leaders who respected that order increased capability without consuming people. Leaders who reversed the order consumed people without increasing capability.

Toyota Production System maturity became visible in whether improvement reduced strain while increasing margin. Systems that improved without pressure demonstrated governed learning. Systems that improved through pressure revealed unmanaged instability.

What This Example Teaches About TPS Leadership

The math in this example remains simple. The leadership thinking required to use the math correctly does not.

Manpower and capacity planning expose whether an organization governs work or reacts to outcomes. The formulas used in planning remain identical across organizations. Maturity does not change the arithmetic. Maturity changes who owns the assumptions, who verifies conditions, and who accepts responsibility for consequences.

Leaders who govern demand, time, and capacity together protect Quality before work begins. Leaders who separate those elements delegate risk to execution. Delegated risk always returns later as defects, missed delivery, overtime, and people strain.

Experience inside Toyota made the difference unmistakable. Leaders who treated planning as governance intervened early, delayed starts when conditions were unclear, and accepted short-term inconvenience to prevent long-term damage. Leaders who treated planning as approval waited for results and explained failure afterward. Both groups used the same numbers. Outcomes diverged completely.

Toyota leadership never asked teams to overcome poor conditions through effort. Leadership accepted responsibility for creating conditions where effort remained normal. People were never expected to compensate for design weakness. Systems were expected to deserve trust before being allowed to run.

Quality protection occurred upstream because leaders refused to treat Quality as an outcome. Quality existed as a condition established through manpower, time, balance, and support. When conditions drifted, leaders corrected conditions rather than demanding results.

Organizations that react to outcomes inevitably focus on symptoms. Retraining replaces redesign. Enforcement replaces learning. Accountability shifts downward. People strain increases while confidence erodes. Leadership explanations grow longer while control diminishes.

Toyota avoided that path by making work governable. Governable work required explicit assumptions, visible time, deliberate margin, balanced design, and daily confirmation. Governance did not rely on persuasion or reporting. Governance relied on presence, verification, and response.

Leadership maturity appeared in choices made before problems existed. Leaders either governed conditions or accepted instability. No middle ground existed.

Once leaders see how early decisions determine later outcomes, the system becomes impossible to unsee. Planning can no longer be treated as neutral. Numbers can no longer be treated as objective. Leadership responsibility becomes explicit.

Toyota Production System maturity is built by governing work before work begins. Systems governed this way protect Quality without heroics. Systems not governed this way consume people while explaining results.

The difference becomes permanent once recognized.

Continuity With Lean TPS Governance Work

This article extends a line of inquiry developed across earlier work on LeanTPS.ca examining how governance was progressively separated from system behavior as the Toyota Production System was translated into portable improvement frameworks.

Earlier articles examine this separation at different structural levels.

Six Sigma (post-1990s) and Lean Six Sigma (post-2010s): How Quality Governance Was Replaced

Examines how certification systems, project structures, and belt hierarchies displaced leadership ownership of Quality, producing technically capable organizations without durable control.

https://leantps.ca/six-sigma-lean-six-sigma-quality-governance/

Kaizen (post-1980s): How Governance Was Removed from the Toyota Production System

Traces how Kaizen became portable by shedding Jishuken, escalation, and leadership obligation, allowing improvement activity to persist while system governance eroded.

https://leantps.ca/kaizen-post-1980s-how-governance-was-removed-from-the-toyota-production-system/

Jishuken: Leadership Governance Through Direct System Engagement

Examines how Toyota preserved Quality by obligating leaders to participate directly in system diagnosis, escalation, and learning, and why the absence of Jishuken left improvement activity disconnected from leadership responsibility.

https://leantps.ca/jishuken/

Why Dashboards and Scorecards Cannot Replace Andon in Lean TPS

Addresses the same governance failure at the operational layer. When visibility tools replace stop authority, response timing, and leadership obligation, Quality becomes informational rather than governed, and loss is explained after it occurs rather than prevented at the point of work.

Lean TPS Disruptive SWOT: Governing Strategic Direction Through Quality and Leadership Obligation

Examines the same failure mode at the strategic layer. When direction is not governed through explicit conditions, ownership, cadence, and response, organizations substitute persuasion and episodic planning for leadership obligation. Lean TPS Disruptive SWOT restores governance by binding strategic direction to verified conditions.

https://leantps.ca/lean-tps-disruptive-swot/

Together, these articles describe a single failure mode expressed at different levels of the enterprise. When governance is removed, visibility increases while control weakens. Lean TPS restores Quality by governing conditions before work begins, not by reporting outcomes after loss occurs.