Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Risk Model™

Visualizing Systemic Risk Before It Breaks the System

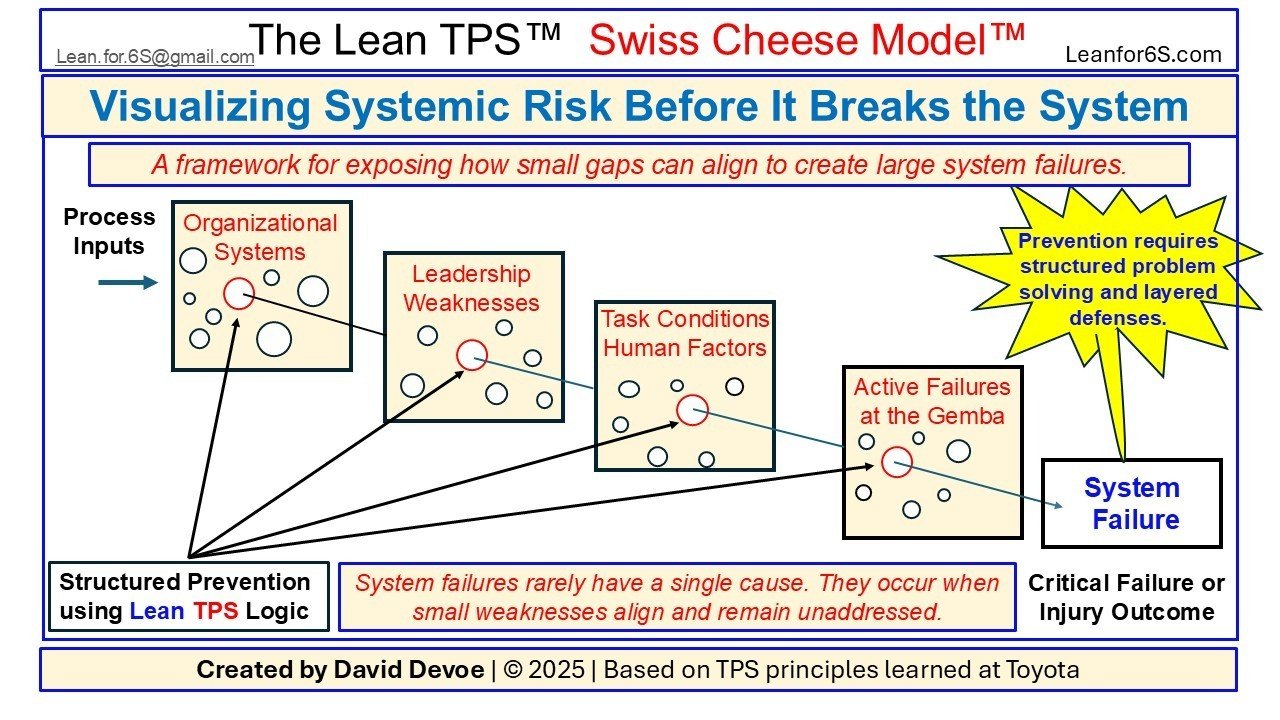

The Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Risk Model™ explains how small weaknesses inside leadership systems, task conditions, and process management can align to create large system failures. This model is grounded in Toyota Production System logic and built to help leaders see and prevent risk before it breaks through.

It combines the principles of Jidoka and Standardized Work to strengthen system visibility, prevention, and leadership capability. Each layer of the model reveals where structure, ownership, and feedback must exist to prevent alignment of hidden risks.

The goal is to help organizations move from reactive problem-solving to proactive system design that protects people, quality, and performance.

Seeing Risk Before It Breaks the System

A visual risk prevention model built on Lean TPS principles, designed to detect system failure before it happens.

What if leaders could see failure forming before it happens?

This article introduces the Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model™, a structured and visual method for identifying system-level risk before it breaks through. While the concept is rooted in the original model by James Reason, this version was built entirely through Lean TPS thinking. It reflects practical experience from TPS training, leadership development, and audit work inside Toyota Industries Corporation, TMHMNA, and Raymond.

The purpose of this model is not to explain failure after it happens. It is designed to help leaders recognize how small gaps in systems, roles, behaviors, and front-line conditions can quietly align into serious outcomes. Each layer represents a point where risk could have been stopped. When those layers fail to support each other, the system becomes exposed.

In this article, I walk through examples where these risks align. Each slide includes a visual scenario and a structured breakdown across four layers: Organizational Systems, Leadership Weaknesses, Human Factors, and Gemba-Level Failures. The outcome is visible. More importantly, each case ends with a Lean TPS response that could have prevented the issue from reaching the customer or causing harm.

This is not a case study in blame. It is a tool for prevention, leadership development, and system reinforcement through structured design.

How to Use This Model

Each of the scenarios in this article includes a visual slide, a risk breakdown, and a narrative explanation. These examples are based on real-world conditions in manufacturing, healthcare, education, construction, logistics, IT, and office environments.

Each case shows how four structural layers failed to reinforce one another. The outcome is stated clearly. A Lean TPS response is included to show how the issue could have been prevented through better system design, ownership, and confirmation.

This model is meant for leaders who want to surface risk early, act with clarity, and prevent failure through daily reinforcement of their systems.

Why Big Failures Start Small

Most systems do not break in one moment. They fail when small weaknesses go unaddressed. The image below introduces the Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model™. It shows how risks build silently across system structure, leadership behavior, human conditions, and daily execution. When no single layer takes ownership, failure can pass through all four.

This visual sets the foundation for what follows. It reveals how failure builds invisibly through misalignment, and how the model helps leaders see that alignment before it leads to harm.

This model shows how small system weaknesses align silently across layers of structure, leadership, human behavior, and Gemba activity. Lean TPS makes these weak signals visible before failure reaches the customer.

Big failures do not usually begin with big problems. They start with small, silent breakdowns that go unnoticed until they align. In Lean TPS, failure is not traced to a single mistake. It results from multiple weak layers that did not prevent the harm. These layers are supposed to stop issues early, but they only work when supported by clear structure, shared responsibility, and real-time leadership engagement.

Each layer in the model is intended to serve as a defense. These layers include Organizational Systems, Leadership Behavior, Human Factors, and Gemba-Level Activity. Without structured prevention and response, those defenses weaken. A missed checklist, an unclear role, a forgotten step, or a delayed reaction can quietly shift pressure to the final layer. When that last layer is exposed, failure breaks through.

This model is not focused on blame. It is a visual A3 that helps leaders and teams understand how small gaps become aligned in complex problems. Most systems continue to run even when early signs of failure are present. The harm appears only when every upstream protection has already failed. Lean TPS prevents this through confirmation, daily structure, clear roles, and the discipline to surface and respond to weak signals early. When small problems are made visible and solved quickly, large failures lose their opportunity to form.

Organizational Systems – Foundation Layer

Organizational Systems are the first layer in the Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model. This is where prevention begins. If the structure at this level is weak, inconsistent, or unclear, it creates silent exposure throughout the system. This image highlights the role of standards, role clarity, and cross-functional coordination in defining system stability. In Lean TPS, these elements are not administrative. They are the foundation of protection.

When Organizational Systems are unstable or undefined, every layer below is left exposed. Structure, coordination, and clear expectations are the first line of defense.

Big failures often begin quietly in the foundation. Organizational Systems define what “normal” looks like. When that definition is unclear, unstable, or missing entirely, every other layer in the system becomes exposed. Most breakdowns start here, long before anything visibly fails.

Common weaknesses at this level include undocumented standards, outdated processes, unclear roles, or misaligned KPIs. These gaps are often ignored or considered temporary, but they allow risk to spread without detection. When no one owns the upstream conditions, the downstream effort has no stable base to stand on.

In Lean TPS, structure is not optional. It is the starting point for prevention. Standardized Work makes expectations clear. Visual Controls reveal status in real time. Just-In-Time connects flow to demand so that everyone sees when the system shifts. These are not tools for convenience. They are strategies for exposing and managing risk.

If this layer is weak, no amount of leadership or frontline response can hold the system together. That is why Lean TPS begins by stabilizing the foundation. Without it, everything else is compromised.

Leadership Weaknesses – Missing Response Structures

This layer shows what happens when leadership response systems are weak or missing. Escalation pathways may exist, but without urgency, presence, or follow-through, they fail to activate. The image highlights the gap between reactive leadership and structured, source-level support. In Lean TPS, leadership is not symbolic. It is a daily function built into how problems are surfaced, owned, and solved.

When leadership is unclear or reactive, small risks are allowed to grow. Structured presence, real-time coaching, and Gemba engagement stop the drift before failure takes hold.

This layer reveals a core truth of Lean TPS. When leadership is absent, unclear, or symbolic, systems begin to drift. Escalation procedures may exist on paper, but they often fail to activate when urgency is needed. Leaders wait for reports or signals that never arrive, and problems are allowed to grow silently.

In many organizations, problem framing is reactive. Leaders engage too late, responding only after the failure has occurred. There is no system for daily visibility or structured reflection. Small risks evolve without ownership or containment. Without consistent Gemba presence, issues that could have been corrected early are missed entirely.

In authentic TPS, this layer is addressed intentionally. Jishuken trains leaders to see and take responsibility for breakdowns. Andon systems give frontline employees the ability to signal for support immediately, without fear or delay. Daily coaching at the Gemba brings leaders into the process, not as inspectors, but as partners in problem-solving.

When this structure is weak, risk builds quietly and becomes normalized. But when leadership is present, grounded, and trained to respond, instability is caught early. Lean TPS does not depend on heroic effort. It embeds reliability by placing leadership where it matters most at the source of the problem.

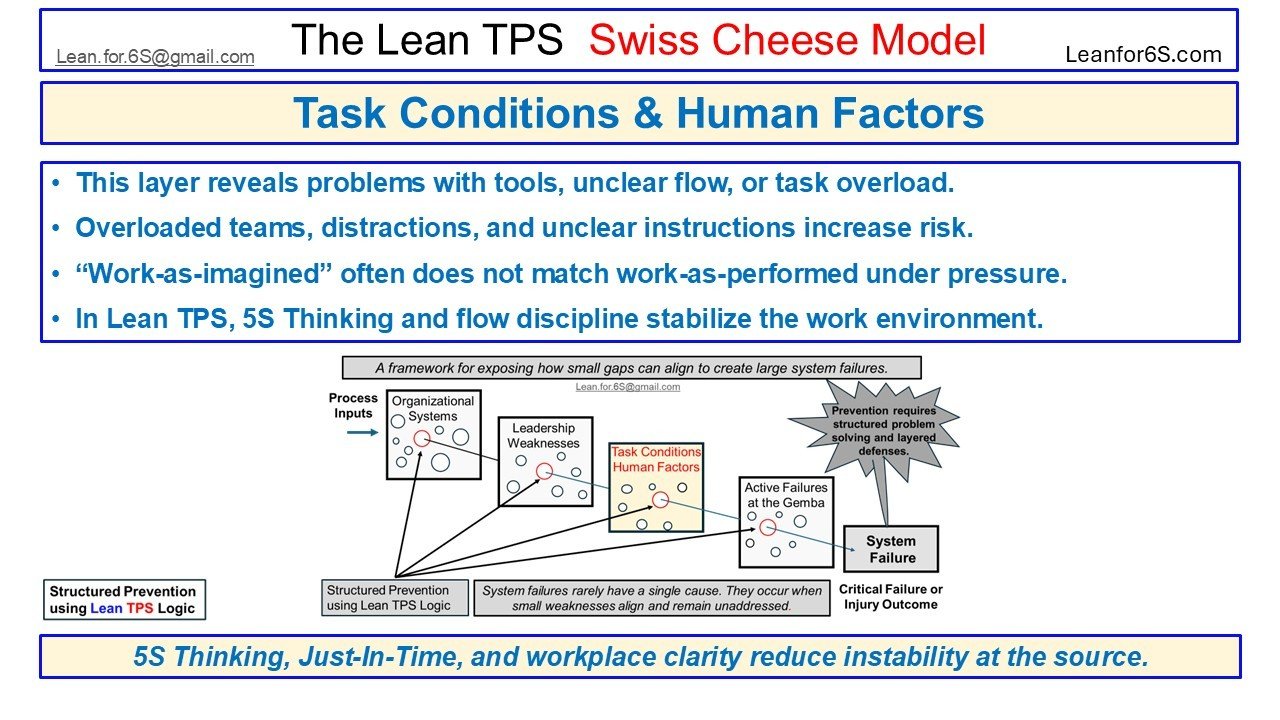

Task Conditions & Human Factors – Work Pressure

This layer focuses on how the real work environment affects performance. Overloaded teams, inconsistent tools, and unclear instructions all increase the chance of error. This image highlights the gap between how work is imagined in procedures and how it actually occurs under stress. In Lean TPS, we do not expect people to be more careful. We strengthen the work conditions around them so the right way becomes the natural way.

Overload, unclear flow, and missing clarity create silent instability. Lean TPS reduces risk by strengthening the work environment, not by placing pressure on people

This layer reveals how poor task design and unstable work conditions can make even skilled people vulnerable to error. When expectations are unclear, tools are inconsistent, or the pace of work is not aligned to the capacity, people begin to rely on habit, shortcuts, or guesswork. Under pressure, the reality of the job often looks very different from what is written in the procedure. What people do is not always what was imagined in policy or training.

This is where Lean TPS reinforces structure. We do not ask people to be more careful. We change the conditions so that the right way becomes the normal way. 5S Thinking removes distractions and defines what good looks like. Standardized Work brings consistency. Flow design aligns work with Just-In-Time principles so that people are not overloaded or left idle.

When human factors are ignored, problems become personal. When systems are built to support people, the risk is reduced at the source. Lean TPS makes safety and quality visible through structure, not supervision. Stability is not something you hope for. It is something you build.

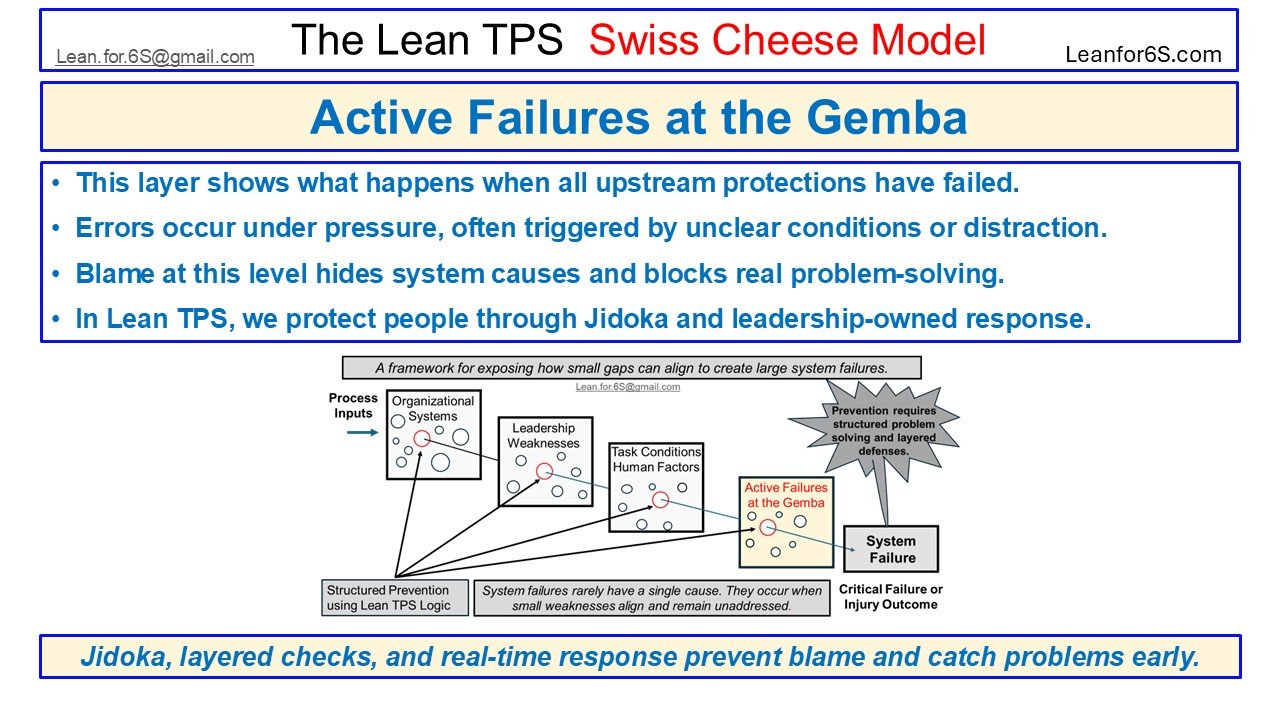

Active Failures at the Gemba – Last Line of Defense

This layer represents the moment when everything upstream has failed. The frontline workers become visible because the system behind them did not catch the risk earlier. This image shows how human error is often treated as the root cause when in reality it is the final symptom of deeper breakdowns. Lean TPS responds not with blame, but with structure. Jidoka creates space to stop, signal, and solve problems at the source.

When the final layer fails, the mistake becomes visible. Jidoka, real-time response, and system redesign stop the cycle and protect people from blame.

This slide focuses on the fourth layer in the Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model. This is the point where the individual becomes visible, but the failure is already in motion. By the time an operator, nurse, agent, or staff member makes a mistake that reaches the customer, the system has already failed. Unclear standards, missing ownership, or weak upstream design created the conditions for this outcome.

These are the moments when urgency overwhelms good judgment, multitasking hides warning signs, or vague instructions meet real-world complexity. In most systems, this is where blame is applied. But in Lean TPS, we do not stop at the person. We go upstream. We trace the conditions that allowed the failure to reach this point.

This layer reminds us that human error is rarely the true root cause. It is a signal that something in the structure or leadership approach allowed risk to continue unchecked. That is why Lean TPS responds with Jidoka. It gives the frontline the power to stop, signal, and surface problems without fear. Leaders then own the responsibility to fix the system.

Jidoka is not about stopping production. It is about stopping harm. It separates blame from response and gives everyone a role in protecting quality and people.

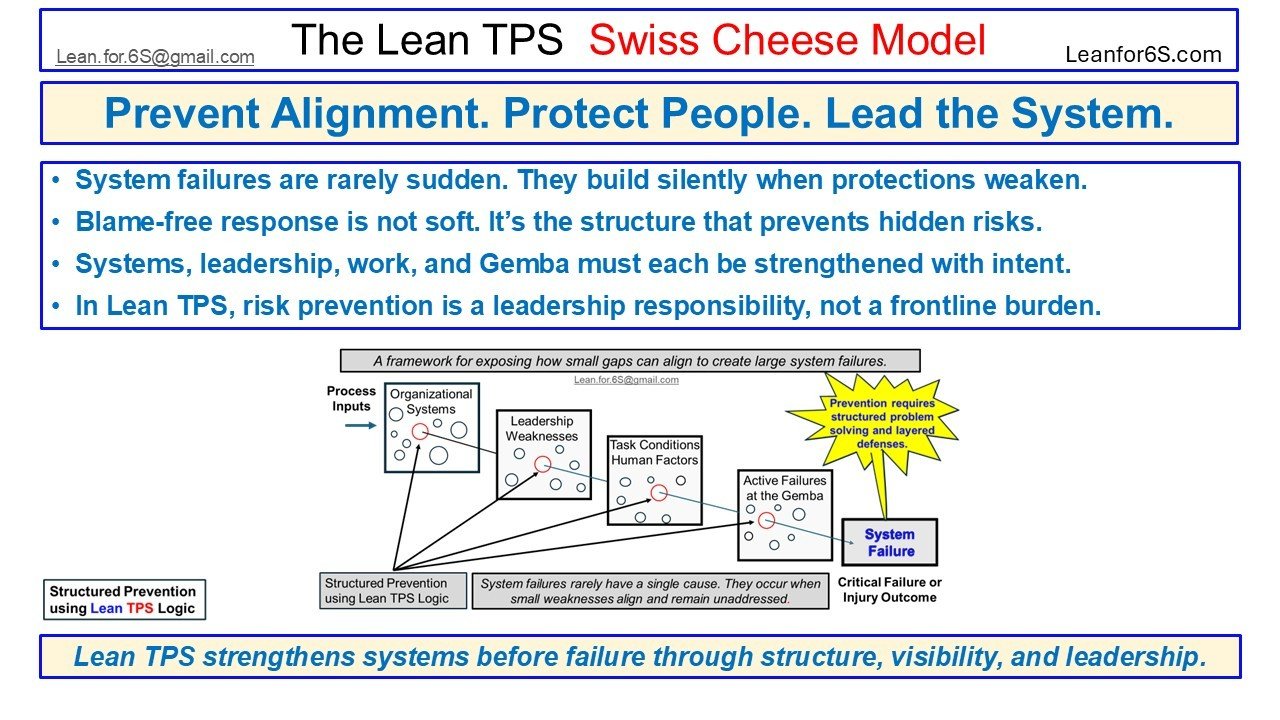

Prevent Alignment. Protect People. Lead the System.

This summary image reinforces the core message of the Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model. System failures are not sudden or random. They form when upstream protections weaken silently. This visual reminds us that leadership is responsible for making risk visible and for reinforcing every layer before alignment occurs. Prevention is not about blame or reaction. It is about structure, visibility, and daily commitment to lead the system.

Lean TPS does not wait for harm before acting. It builds daily systems that expose risk early and place leadership at the center of prevention.

This final slide introduces the purpose of the Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model. It is a visual method for understanding how system failures occur not from one major error, but from many small weaknesses that silently align. Most organizations do not see the risk until it reaches the frontline, but by then the system has already failed.

Failures often begin in weak or unstable structures. They continue when leadership is unclear or disconnected. They pass through inconsistent tasks or overloaded work. They finally reach the Gemba, where the problem becomes visible, and the person closest to it takes the blame.

In Lean TPS, prevention is a leadership responsibility. It is not placed on the frontline. Blame-free systems do not remove accountability. They clarify it through the Lean TPS structure. This includes clear escalation roles, visual control, routine confirmation, and built-in response systems that reveal problems before alignment occurs.

The goal of this model is not to explain failure after the fact. It is to help leaders see how to prevent it upstream. We prevent alignment by reinforcing every layer. We protect people by designing systems that support them. And we lead by building conditions that expose risk early and act before harm is done.

Real-World Scenarios Using the Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model

These examples show how small system weaknesses align into visible failure when not caught early. Each scenario is based on real conditions observed in aviation, healthcare, manufacturing, IT, education, logistics, construction, finance, and public services. In every case, risk accumulated silently across four structural layers: Organizational Systems, Leadership, Human Factors, and Gemba-level activity. The goal is not to assign blame, but to show how Lean TPS makes risk visible and actionable before harm occurs regardless of industry.

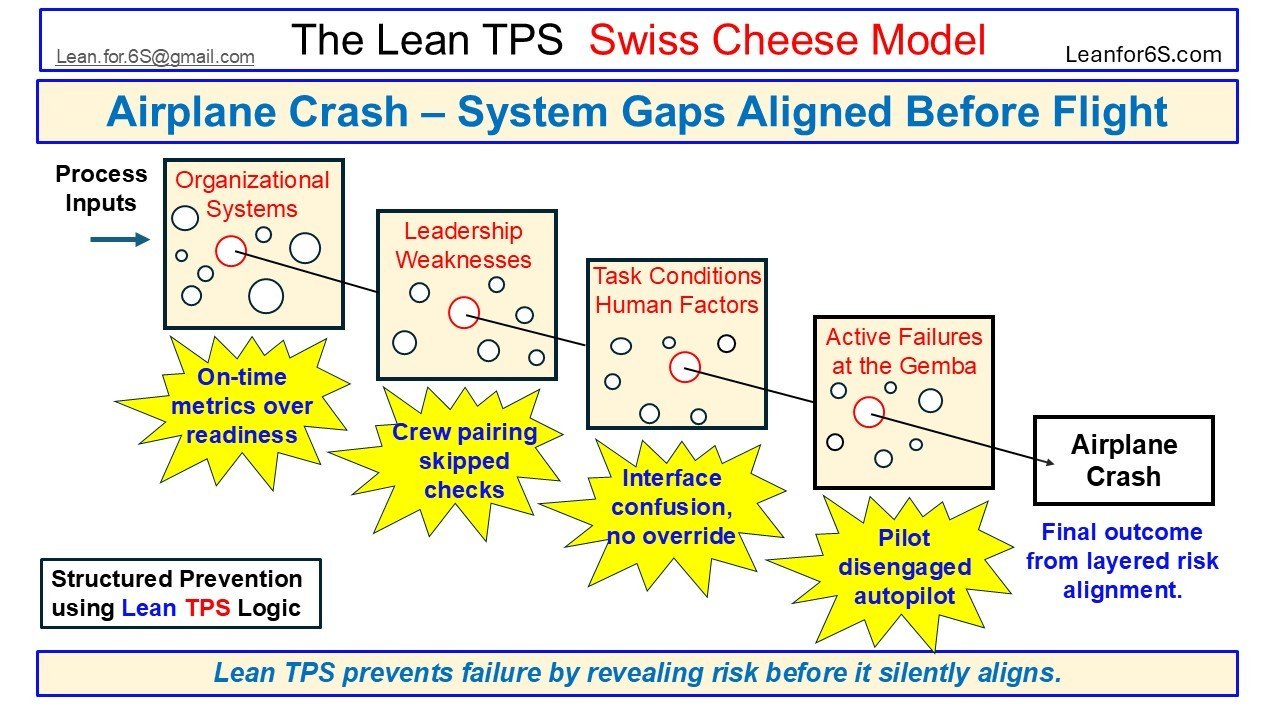

Airplane Crash – System Gaps Aligned Before Flight

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems: On-time metrics were prioritized over readiness. Organizational pressure focused on schedule performance instead of complete pre-flight checks. Readiness was assumed rather than confirmed.

- Leadership Weaknesses: Crew pairing protocols were skipped. Leadership did not enforce structured verification between team members. Key preflight tasks were bypassed without accountability.

- Task Conditions and Human Factors: The autopilot interface was confusing and offered no manual override. Pilots were unclear about the actual system status under pressure.

- Active Failures at the Gemba: In a moment of uncertainty, the pilot manually disengaged the autopilot without understanding the downstream effects.

Outcome: The airplane crashed. Multiple hidden weaknesses combined to eliminate recovery margin. No single cause triggered the event, but their alignment created failure.

Lean TPS Response: Lean TPS prevents this by building in readiness, clear roles, visual confirmation, and engineered fail-safes. In high-risk systems, judgment alone is not enough. Lean TPS structure protects people before failure begins.

Failure did not result from one action. It came from multiple system gaps that silently aligned before flight and removed the margin for recovery.

This example illustrates how catastrophic outcomes rarely result from a single mistake. In aviation, failure often builds quietly through layers of small gaps. These gaps accumulate across systems, roles, tools, and decision-making, and only align at the worst possible moment.

At the organizational level, there was pressure to maintain on-time departures. That emphasis reduced attention to full system readiness. Departure metrics were tracked, but process health was assumed rather than confirmed.

At the leadership level, crew pairing and cross-check procedures were skipped. There was no accountability for ensuring shared responsibility before the flight. Key checks were either rushed or bypassed entirely.

Within task conditions, the aircraft interface made the situation worse. It lacked clarity, and no manual override was available. In a high-stress moment, the pilots could not confirm the aircraft status or control logic.

At the Gemba, the pilot disengaged the autopilot, not realizing that every layer behind him had already failed. The action revealed how little safety margin remained.

This was not one bad decision. It was a system that removed its own protection step by step. Lean TPS addresses this by building structure into daily operations before risk aligns and before it becomes fatal.

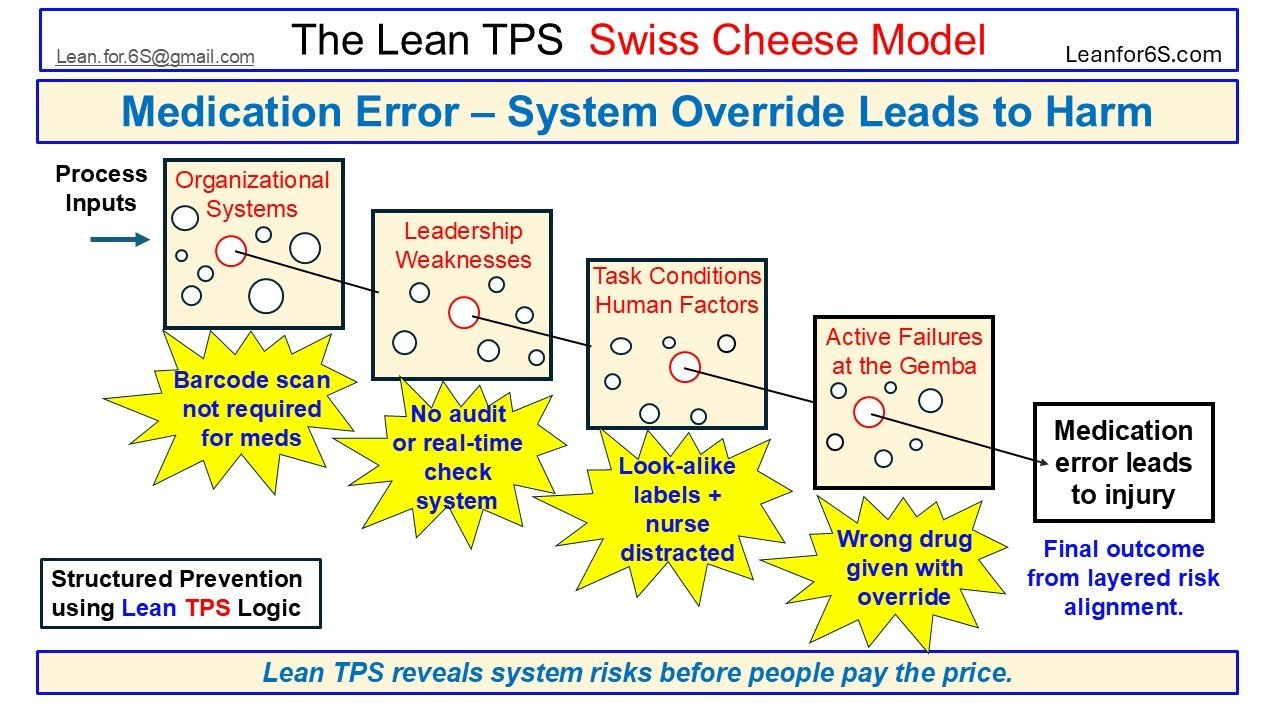

Medication Error – System Override Leads to Harm

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems: Barcode scanning was not required for medication administration. The system allowed drugs to be given without confirmation, and this basic check was not embedded into the standard workflow.

- Leadership Weaknesses: There was no real-time audit or oversight process. Leaders had not built a structure to review overrides or verify that safety protocols were being followed.

- Task Conditions and Human Factors: The nurse was multitasking in a high-pressure environment. Packaging was confusing, with multiple drugs labeled similarly. The system relied on vigilance rather than clarity.

- Active Failures at the Gemba: The wrong drug was given using a manual override. No second check was performed. The error reached the patient before anyone recognized the mistake.

Outcome: A patient was harmed by a preventable medication error. The system failed to protect them, even though the people involved were experienced and well-intentioned.

Lean TPS Response: Lean TPS eliminates optional safeguards. Barcode checks must be built into the standard flow. Labeling must reduce doubt, not increase it. Leaders must maintain visibility, audit risk in real time, and build response systems that support safe decisions under pressure.

This medication error was not caused by one action. It was the result of missing structure, silent overrides, and unclear conditions that aligned before harm occurred.

This scenario reveals how a medication error did not result from a single bad choice. It was the product of silent system failures across four layers that allowed harm to reach the patient.

At the Organizational Systems level, barcode scanning was available but not required. The safeguard existed, but staff could bypass it, and the workflow did not enforce its use. This left a critical safety check to personal discretion.

Leadership had not closed the gap. There was no structured system to monitor overrides or to track real-time medication risks. Audits were inconsistent and typically conducted only after an error had occurred.

Within Task Conditions, the nurse was working under pressure, juggling multiple patients and distractions. Medication packaging used look-alike labels that made it easy to confuse products. Instead of removing risk, the system demanded constant vigilance.

At the Gemba, the nurse administered the wrong drug using a manual override. No secondary check was performed, and the mistake reached the patient before anyone intervened.

In Lean TPS, we do not respond with blame or retraining alone. We build systems that make safe actions the easiest ones. This includes hardwired barcode checks, clear visual cues, and structured support for frontline decisions. Risk is prevented through daily design, not judgment under pressure.

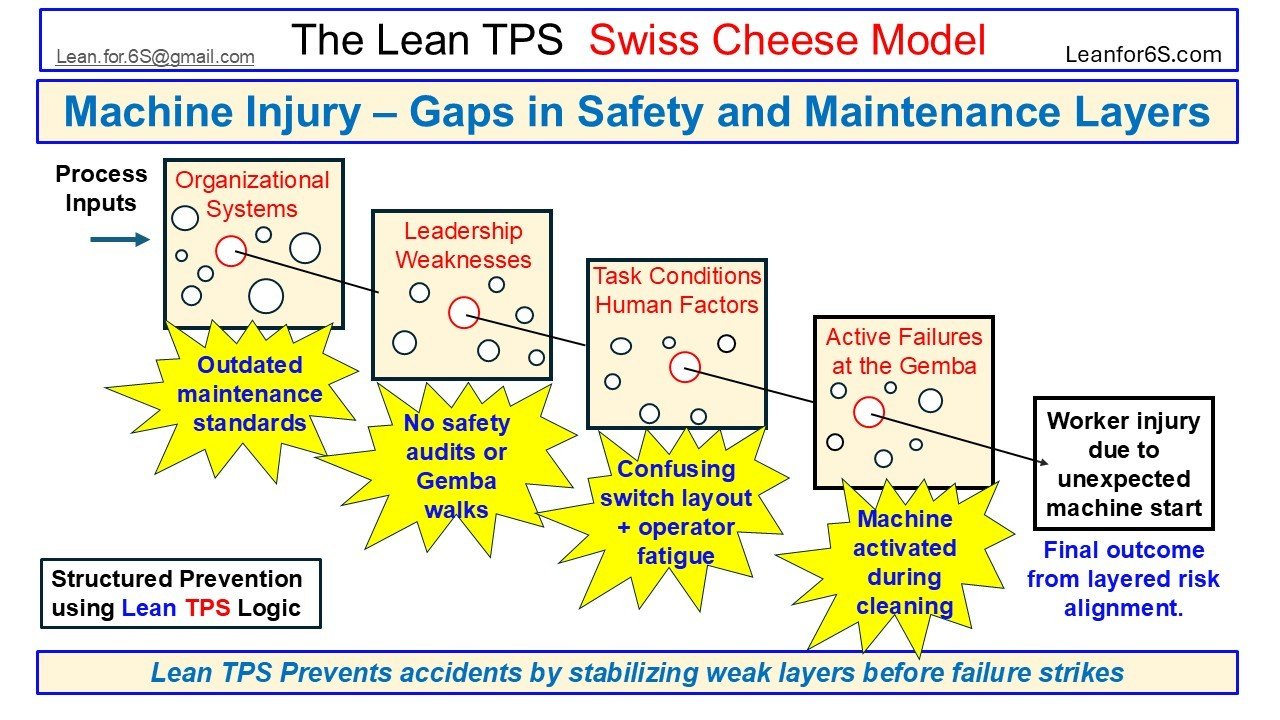

Machine Injury – Gaps in Safety and Maintenance Layers

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems: Maintenance standards were outdated. Lockout/tagout protocols were unclear or missing. Safety checks for cleaning procedures were not included in standard operating documents.

- Leadership Weaknesses: There were no recent Gemba walks or safety audits. Leadership had not verified compliance with safety routines or observed how the machine was actually used.

- Task Conditions and Human Factors: The operator was fatigued and faced a confusing switch layout. Labels were unclear, and there was no reliable indicator that the machine was fully deactivated.

- Active Failures at the Gemba: While cleaning the equipment, the worker unknowingly triggered activation. There was no backup mechanism to detect presence or prevent motion during cleaning.

Outcome: A worker was seriously injured by an unexpected machine start. The system did not protect them because every layer that should have prevented the event was weakened or absent.

Lean TPS Response: Lean TPS reinforces safety through structure. Updated procedures, switch clarity, visual confirmation, and Gemba-based leadership checks must be standard. Jidoka is not just a concept it is a mechanism for stopping risk before someone gets hurt.

The injury did not happen because someone failed. It happened because every protection layer was weak, unclear, or missing when it mattered most.

This incident shows how worker safety can be compromised not by a single error, but by the quiet failure of multiple system layers. The Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model helps reveal where each layer broke down and how the injury could have been prevented with structured discipline.

At the Organizational Systems level, machine maintenance protocols had not been updated. There was no formal lockout procedure during cleaning, and the standard operating procedures did not clearly define how to prevent restart risk. The process left critical steps undefined.

Leadership failed to detect the risk. No Gemba walks had been conducted, and no recent audits were in place to confirm that procedures were followed safely. Without structured oversight, unsafe conditions remained invisible.

In the Task Conditions layer, the operator was tired and uncertain. The control panel had a confusing layout, and switch labeling was unclear. There was no way to confirm visually or physically that the machine was safe to enter.

At the Gemba, the worker entered the machine during cleaning, and it was partially activated. No backup signal, presence detection, or secondary lockout stopped the event. The result was a preventable injury.

Lean TPS does not wait for someone to get hurt. It builds safety into daily work through Gemba confirmation, clear roles, visual safeguards, and fail-safe responses. When every layer is strong, failure cannot align.

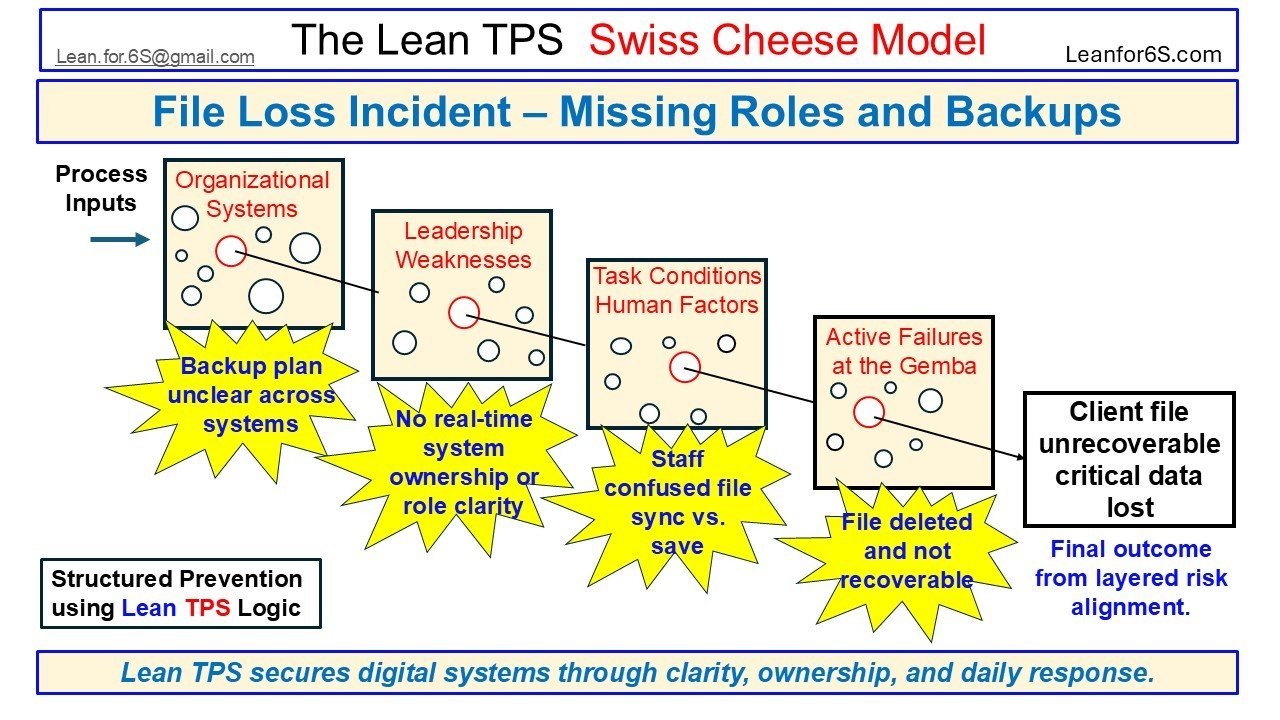

File Loss Incident – Missing Roles and Backups

Systemic Risk Breakdown

1. Organizational Systems Backup plan unclear across systems. There was no unified or enforced protocol for file retention, storage location, or restoration across platforms. Each team followed different habits with no shared safety net.

2. Leadership Weaknesses No real-time system ownership or role clarity. Responsibility for data protection was undefined. Leaders assumed backup systems were functioning, but no verification routines or accountability structures were in place.

3. Task Conditions – Human Factors Staff confused file sync versus save. A team member believed syncing the document meant it was safely stored. Under time pressure and without confirmation prompts, the file remained vulnerable to loss.

4. Active Failures at the Gemba File deleted and not recoverable. After use, the file was deleted under the assumption it had already been saved. No one noticed the mistake until it was too late.

Outcome Client file unrecoverable, critical data lost. An important document was permanently lost. The result was missed deliverables, reduced trust, and organizational damage.

Lean TPS Response Lean TPS builds visible digital safeguards through role clarity, standard file protocols, and daily confirmation routines that prevent the alignment of silent risks.

Routine IT task reveals how unclear backup roles and silent assumptions can align to cause permanent data loss.

This digital failure shows how even routine IT actions can silently lead to permanent data loss. The issue was not a one-time mistake. It was a system-wide breakdown where structure, clarity, and accountability were all missing.

At the organizational level, file backup procedures were inconsistent and poorly defined. Different platforms were used without a shared retention strategy or recovery method. This created invisible gaps between teams and tools.

Leadership did not assign responsibility. No one was actively accountable for ensuring file protection or verifying save-and-restore capabilities. Backups were assumed to have existed but never confirmed.

On the ground, a staff member mistook a synced file for a saved file. The platform provided no confirmation prompt. Under typical time pressure, that small distinction went unnoticed.

At the Gemba, the file was deleted without realizing it had not been secured. By the time the error surfaced, the file was gone. It was not recoverable, and the outcome was a serious loss of trust and client confidence.

Lean TPS handles this with structure, not blame. It builds file protection into daily work through clear roles, visible confirmation steps, and leadership routines that make safety part of normal flow. Digital work needs the same layered protection as any physical process.

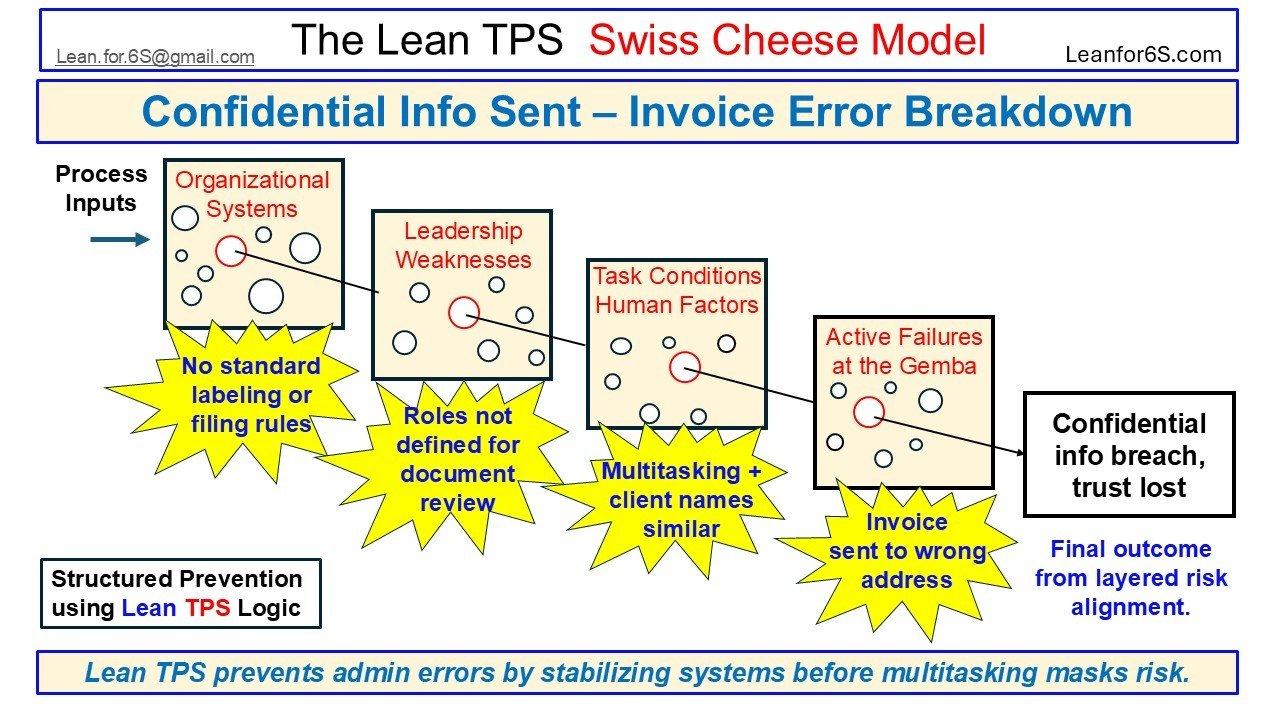

Invoice Sent Without Checkpoint

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems No standard labeling or filing rules. There were no defined conventions for file names or version tracking. This led to confusion over similarly named client records.

- Leadership Weaknesses Roles not defined for document review. No one was assigned responsibility for verifying sensitive document addresses before sending. The task fell between roles.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors Multitasking and client names were similar. The Administrative staff were processing multiple requests at once. Clients had similar names, and no pause or check was built into the workflow.

- Active Failures at the Gemba Invoice was sent to the wrong address. The document was sent to a different client with a similar name. There was no system-based warning or stopgap.

Outcome Confidential info breach, trust lost. Sensitive financial data was shared with an unintended recipient. This led to reputational harm and client concern over data handling.

Lean TPS Response Stabilize admin processes with clear standards, ownership, and pacing. Build confirmation into flow, and avoid relying on memory or multitasking.

Lean TPS stabilizes admin systems to prevent errors hidden by multitasking.

This example shows how an administrative process can quietly break down and lead to a breach of trust not through gross error, but through the silent alignment of weak systems. It began at the organizational level. There were no file naming conventions, no standard folder structures, and no rules for managing confidential invoices. Versions were difficult to track and easy to confuse.

At the leadership level, no one was clearly assigned to verify outgoing documents. The task was informal and shared across roles. Without ownership, no one was watching closely.

In the task environment, staff were multitasking and working quickly. Several clients had similar names, and there was no workflow pause to confirm accuracy. Visual layout and screen design did not help. Under pressure, the wrong file was selected and sent.

At the Gemba, the invoice was emailed to the wrong client. No one caught it until the unintended recipient flagged the issue.

Lean TPS does not blame individuals. It reinforces daily structure that protects quality before damage occurs. In admin work, this includes clear labeling, defined roles, double-checks, and workflow pacing. Trust is not lost in one moment. It is lost when small risks go unaddressed. Lean TPS prevents that by building daily systems that protect people and reputations.

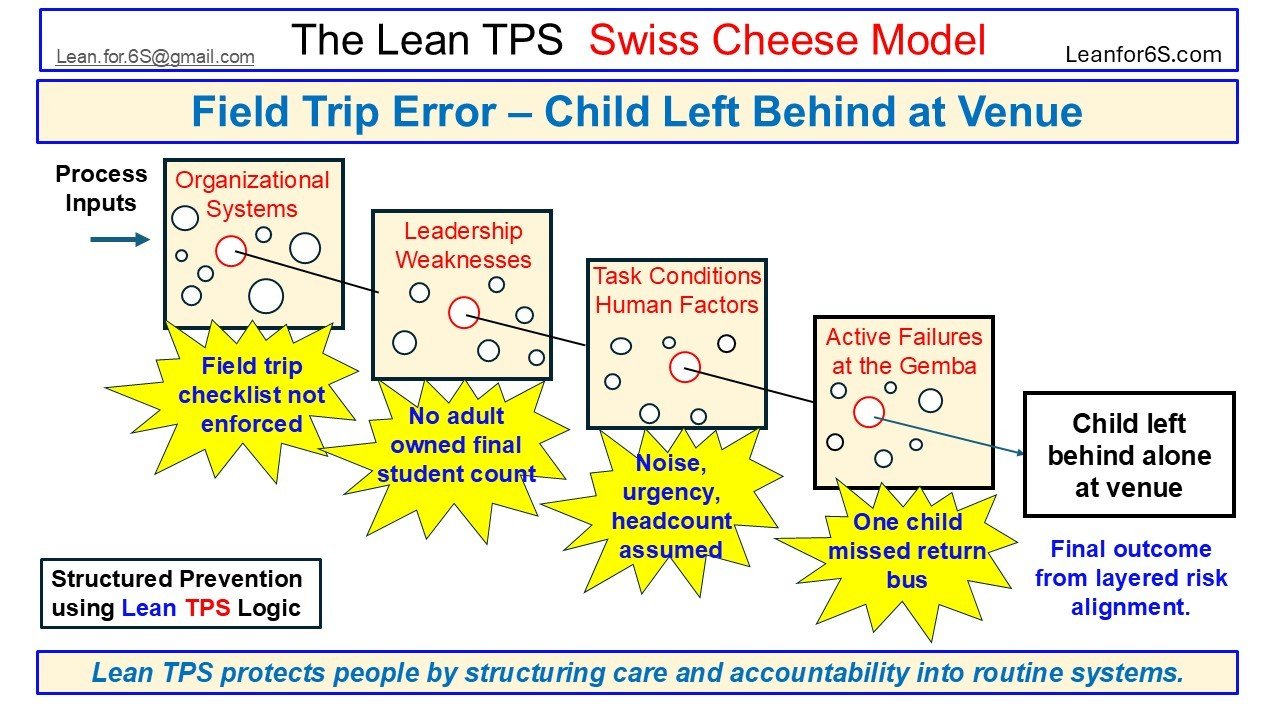

Child left at the venue from unclear headcount roles

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems Field trip checklist not enforced. No system verified that departure protocols were followed. The process relied on habit, not confirmation.

- Leadership Weaknesses No adult owned the final student count. Accountability for verifying the student return was not clearly assigned to any one person.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors Noise, urgency, and headcount assumed. Amid distractions and time pressure, staff assumed all children had returned without performing a physical count.

- Active Failures at the Gemba One child missed the return bus. The student was left behind during reboarding. No backup check or redundant process caught the omission.

Outcome Child left behind alone at venue. Emergency action was required after the error was discovered. The child was unharmed but deeply distressed.

Lean TPS Response Design safety into departure with structured checklists, role clarity, and layered confirmation. Never rely on good intentions.

A student was left behind because no one owned the final headcount and no system enforced the checklist. Lean TPS replaces assumptions with structure to protect people.

This incident shows how a simple oversight can escalate into a serious event when weak systems go unnoticed. A child was left behind during a field trip not because a single person failed, but because multiple layers silently broke down.

At the system level, the field trip checklist was not enforced. While the plan existed, it was not embedded into a daily routine or reinforced through structured accountability. Leadership failed to assign ownership of the final headcount. No adult was explicitly responsible for confirming every student’s return before departure.

As the group prepared to leave, noise and urgency created a distraction. Adults assumed everyone was present. There was no calm pause, no structured double-check. The student was not on the bus.

This was not caused by negligence. It was caused by a system that did not support people under pressure.

In Lean TPS, safety is not a matter of good intentions. It is built into the structure. Processes involving vulnerable individuals require visual confirmation, role clarity, and layered checks. Whether in a plant or on a field trip, we must stabilize routines to protect people.

We do not blame the teacher. We fix the system that left them unsupported. Lean TPS protects people by designing care, accountability, and confirmation into the normal flow of work.

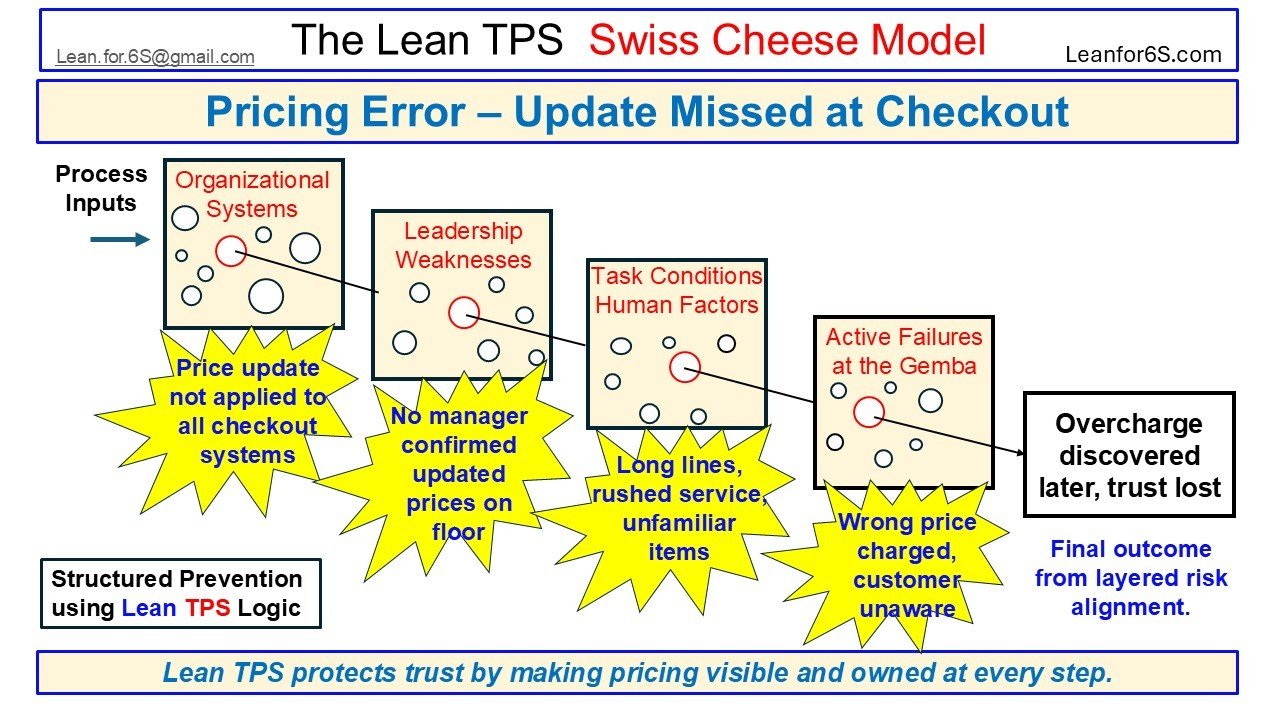

Price Update Missed, Checkout Mismatch

Systemic Risk Breakdown

1. Organizational Systems Price update not applied to all checkout systems. The update was pushed through some Point of Sale (POS) terminals but not others. The inconsistency was not caught because no system enforced confirmation across all registers.

2. Leadership Weaknesses No manager confirmed updated prices on the floor. Leadership assumed updates were complete. There was no assigned ownership or structured walk to verify price alignment between signage and checkout.

3. Task Conditions – Human Factors Long lines, rushed service, unfamiliar items. Frontline staff were working quickly to reduce wait times. They relied on memory rather than checking the system. No feedback loop was available to support price validation.

4. Active Failures at the Gemba Wrong price charged, customer unaware. The cashier scanned an outdated price. The mismatch was not noticed until after the purchase. The system lacked a prompt or visible price check.

Outcome Overcharge discovered later, trust lost. The customer felt misled. Although the error seemed minor, it created doubt in the store’s pricing integrity and affected future purchase decisions.

Lean TPS Response Build verification into every layer. Use Standardized Work, visual price confirmation, and structured leadership response to prevent mismatches before checkout.

Incorrect price charged when updates failed to sync across systems

This pricing error may seem minor, but its impact on customer trust was significant. A store-wide price update was not applied consistently across all checkout systems. One register continued charging the outdated amount while others reflected the correct price. The mismatch went unnoticed until after the customer had left.

The failure began upstream. There was no standardized process to ensure all POS terminals received the update. Leadership assumed the change had been completed but did not verify it on the floor. No structured walk or confirmation check was in place.

At the task level, staff were handling long lines, unfamiliar items, and pressure to move quickly. They worked from habit and did not confirm prices. The system provided no visual or audible prompt to highlight the inconsistency.

At the Gemba, the customer paid the wrong amount. The cashier did not catch the error, and the receipt was not reviewed at the register. The error only came to light later, when the customer reviewed the purchase at home.

Lean TPS handles this through layered confirmation, not assumption. Standardized Work, leadership walks, and visible pricing controls protect brand integrity. Price accuracy is not just a transaction. It is a signal of trust and trust is built through structure.

Tracking Failure with No Delivery Confirmation

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems No shared tracking system across carriers. Different systems were used without integration, so no one could monitor status, or detect failure early.

- Leadership Weaknesses No accountability for exception follow-up. There was no defined process or person responsible for investigating delivery issues once they occurred.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors Staff assumes packages re-routed. Without visibility or confirmation, the team assumed the issue resolved itself, delaying any response.

- Active Failures at the Gemba Wrong destination entered, no confirmation. The shipping error was never verified. No validation step was built into daily operations.

Outcome Time-sensitive shipment lost, customer escalates. A preventable error became a customer crisis due to a lack of structure and ownership.

Lean TPS Response Clarify roles, verify destinations, and build confirmation steps into routine logistics. Prevention requires visibility and structured accountability.

Shipment tracking broke down across silos, no one followed up.

This slide illustrates how a seemingly small delivery error can become a critical failure when multiple systems lose visibility. A time-sensitive shipment was lost, not because of one mistake, but because of layered, unaddressed weaknesses.

There was no shared tracking system across carriers. Internally, no single person owned the delivery exception. The leadership layer lacked escalation protocols or visual cues. Staff assumed the shipment had been rerouted, but no confirmation process was built in. At the Gemba, the wrong destination was entered with no check or stop point. By the time the customer escalated, trust and time were both gone.

Lean TPS protects delivery systems not with speed alone, but through disciplined flow clarity. Ownership must be structured, not left to assumption. Confirmation of destination, visual accountability for exceptions, and layered prevention allow organizations to see risk before it crosses into loss.

This is not just about logistics. It applies across healthcare, manufacturing, service, and retail. Wherever something must reach someone reliably, Lean TPS reveals where flow breaks before people suffer the consequences.

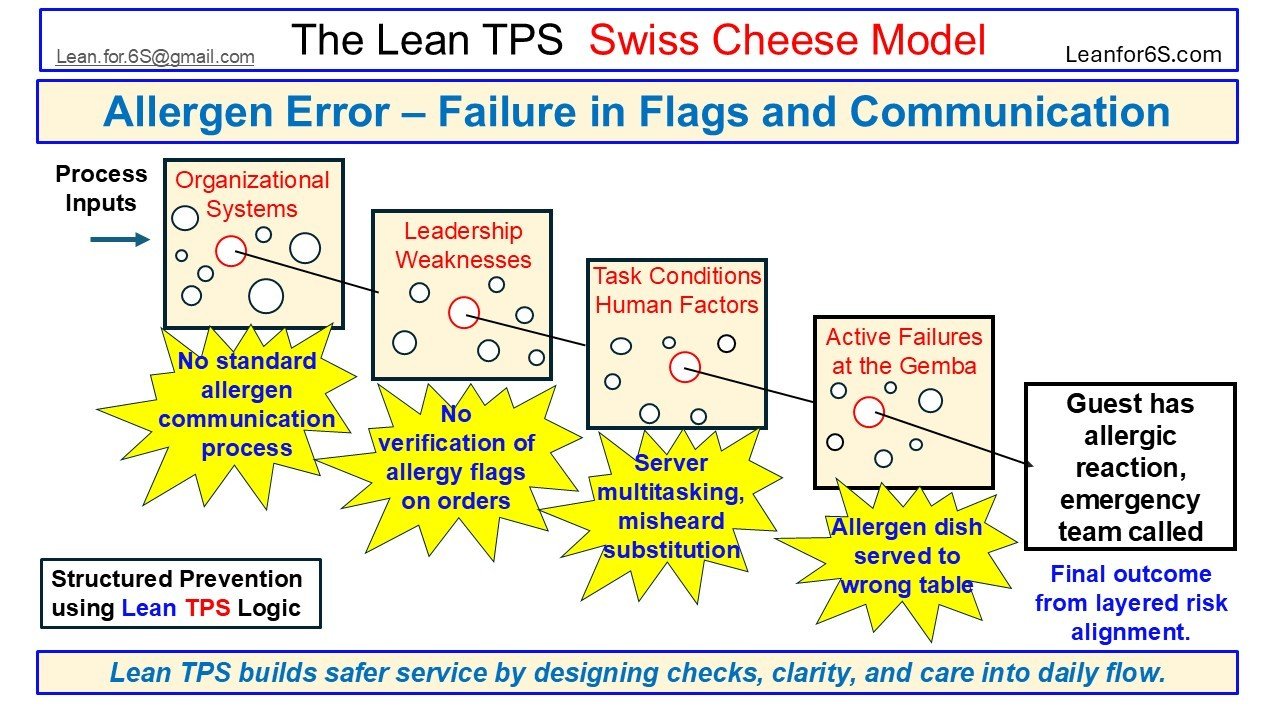

Failure to verify allergen flags allowed unsafe food to reach the guest.

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems No standardized allergen communication process was in place. The restaurant had no system-level routine for ensuring allergy information traveled from order to kitchen to table.

- Leadership Weaknesses No verification step existed to confirm allergy flags on orders. Managers did not embed or enforce a structured confirmation process.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors The server was multitasking under pressure and misheard a substitution request. Distractions and pace made active listening difficult.

- Active Failures at the Gemba An allergen-containing dish was served to the wrong table. There was no table number check or visual alert to prevent the error.

Outcome The guest had a severe allergic reaction and required emergency medical assistance. A preventable system failure escalated into a health crisis.

Lean TPS Response Lean TPS builds layered protection using standardized work, role clarity, confirmation steps, and Jidoka. Safety is not left to chance it is structured into daily service.

Allergen flags missed in fast-paced service; guest served wrong meal, emergency response triggered.

This slide presents a high-consequence service failure: an allergen reaction caused by a system-wide communication breakdown. The error was not just at the point of service. It was built into the system long before the dish reached the guest.

There was no standardized allergen communication process in place. Leadership did not confirm whether allergy flags were integrated into the ordering workflow. At the task level, the server was likely multitasking under pressure and misheard a substitution request. At the Gemba, the allergen-containing dish was served to the wrong table without any double-check.

The result was serious. A guest suffered an allergic reaction, and an emergency response had to be called.

In Lean TPS, this is not viewed as an isolated error. It signals a pattern of upstream weakness and missing checks. Effective prevention requires visual cues, confirmation steps, structured handoffs, and clear responsibility. Fixing the process means designing safety into every layer not relying on memory or good intentions.

Whether in hospitality, healthcare, or education, Lean TPS builds safer systems by embedding care, clarity, and accountability into routine work before problems reach the people we serve.

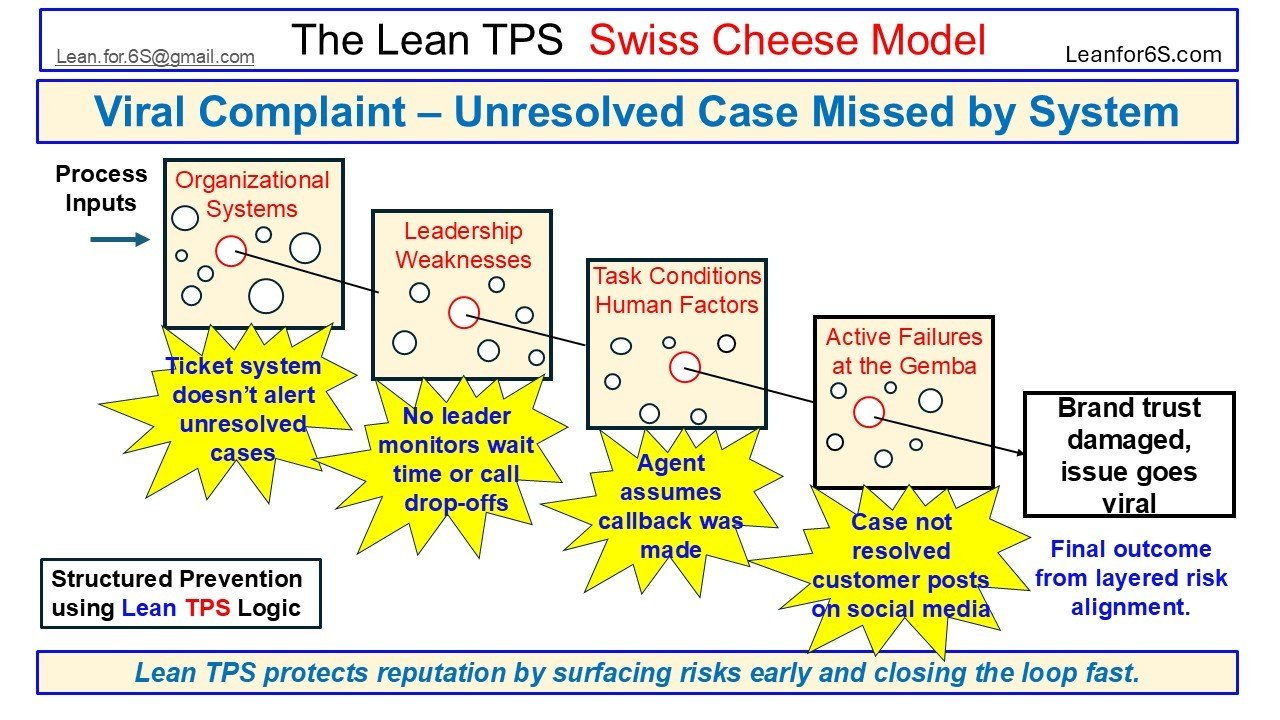

Viral Complaint – System Failed to Flag Risk Early

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems The Ticket system doesn’t alert unresolved cases. The Customer Relationship Management (CRM) or helpdesk platform lacked built-in logic to flag or escalate unresolved tickets. Cases quietly aged without visibility or prompts.

- Leadership Weaknesses No leader monitors wait time or call drop-offs. Supervisors did not review abandoned calls or stale tickets. No one tracked which issues stalled or how long customers waited.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors Agent assumes callback was made. Amid multitasking, the agent believed someone else had followed up. There was no verification loop or team-level confirmation process.

- Active Failures at the Gemba Case not resolved, customer posts on social media. The issue never received proper attention. Frustrated, the customer shared the experience online, bypassing internal resolution.

Outcome Brand trust was damaged, issue goes viral. The organization lost control of the narrative. A silent case became a public failure that damaged reputation.

Lean TPS Response Use Lean TPS to surface unresolved risks before customers do. Embed visibility, daily ownership, and loop closure into every system.

Lean TPS protects reputation by surfacing risks early and closing the loop fast.

This slide shows how an unresolved customer complaint can quietly build into a public crisis when structure and visibility are missing at every level. A case was opened, but no alert flagged it as unresolved. Leadership failed to review lagging tickets or follow up on dropped calls. The agent, working under pressure, assumed a colleague had completed the callback. At the front line, the case simply sat unanswered. The customer eventually took their frustration online, and the issue went viral.

In Lean TPS, this is not viewed as an isolated agent mistake. It is a system-level breakdown across multiple layers: digital platforms without alerts, leaders without monitoring standards, and frontline processes without confirmation or closure. Structured prevention means designing systems that surface problems early. When unresolved cases are flagged and owned in real time, they can be addressed before trust is lost.

TPS builds this discipline into daily work. Visual dashboards, layered alerts, and clear ownership routines prevent small issues from becoming brand-wide failures. In customer service, as in production, the goal is to catch failure while it is still recoverable. Silence is not neutral it is a signal. Lean TPS makes sure that the signal is seen before damage is done.

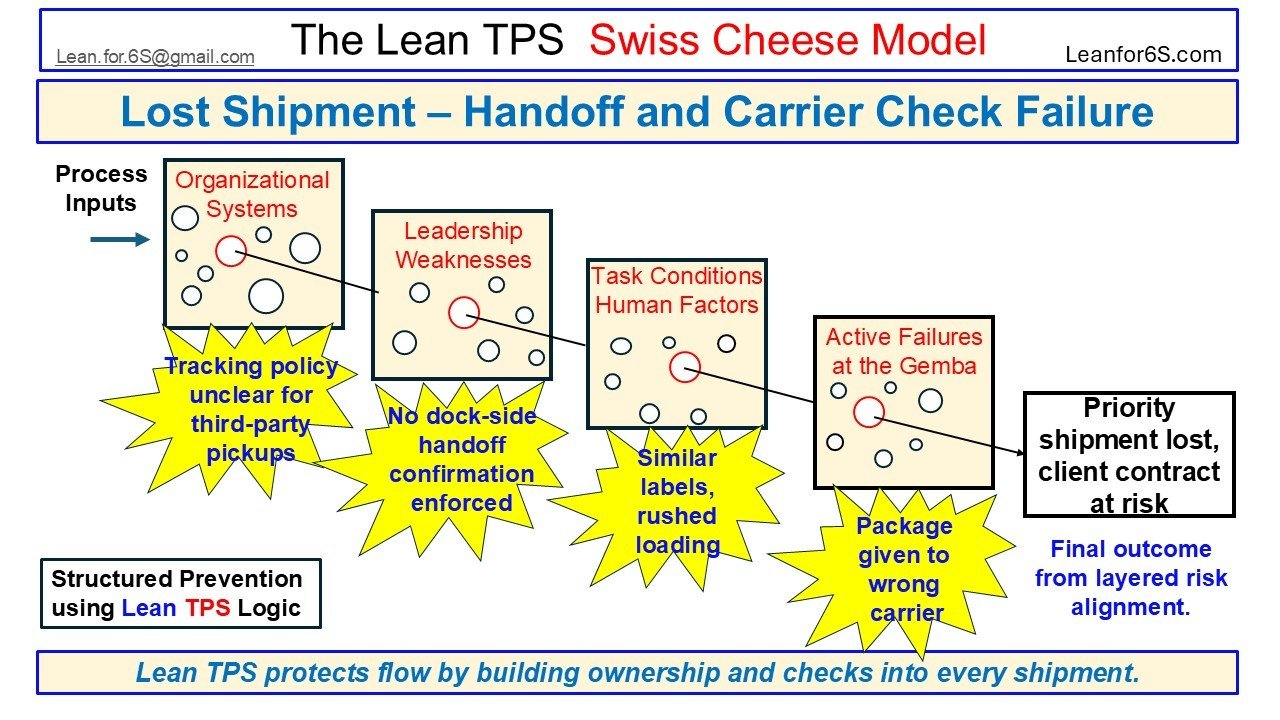

Carrier Handoff Miss – No Confirmation System in Place

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems Tracking policy unclear for third-party pickups. There was no standardized rule or process to verify who was authorized to collect priority shipments. Carrier identity and destination were assumed instead of confirmed.

- Leadership Weaknesses No dock-side handoff confirmation enforced. Leaders did not require a visible final check between shipping staff and external carriers. Handoff procedures were informal and accountability was diffuse.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors Similar labels, rushed loading. In a fast-paced dock environment, packages were labeled similarly and loaded under time pressure. Verification was bypassed in favor of speed.

- Active Failures at the Gemba The package was given to the wrong carrier. In the absence of structured checks, the wrong shipment was handed off. No immediate error detection mechanism existed at the moment of transfer.

Outcome Priority shipment was lost, client contract is at risk. The package was never delivered. The client’s confidence was shaken and contract renewal was jeopardized. The damage extended beyond the shipment itself.

Lean TPS Response Lean TPS embeds handoff verification, ownership, and visual confirmation into every shipment process. Mistakes are not isolated they are system signals that must be made visible and preventable.

Lost shipment handed to the wrong carrier during rushed loading. No tracking or confirmation checks were built into the process.

This slide illustrates a costly logistics breakdown where a high-priority shipment was lost due to a failure in the handoff process with a third-party carrier. The organizational system lacked a clear policy for identifying and tracking external pickups. Leadership did not enforce any visual or documented handoff confirmation at the dock. The pressure to move quickly led staff to load packages based on assumption. Labels were similar, urgency was high, and no step was built into the flow to verify carrier or destination.

At the Gemba, the shipment was handed to the wrong party. No one realized the error until the customer raised a concern. By then, the shipment was lost, the customer relationship was at risk, and the business impact had already escalated.

In Lean TPS, this failure would not be blamed on speed. It would be recognized as a gap in structure. Ownership, verification, and confirmation must be standard parts of the daily flow. Handoff moments are not routine they are risk points that require disciplined clarity. Lean TPS responds with visible standards, not verbal reminders. Every shipment deserves the same care as every product because the customer’s trust is always in the box.

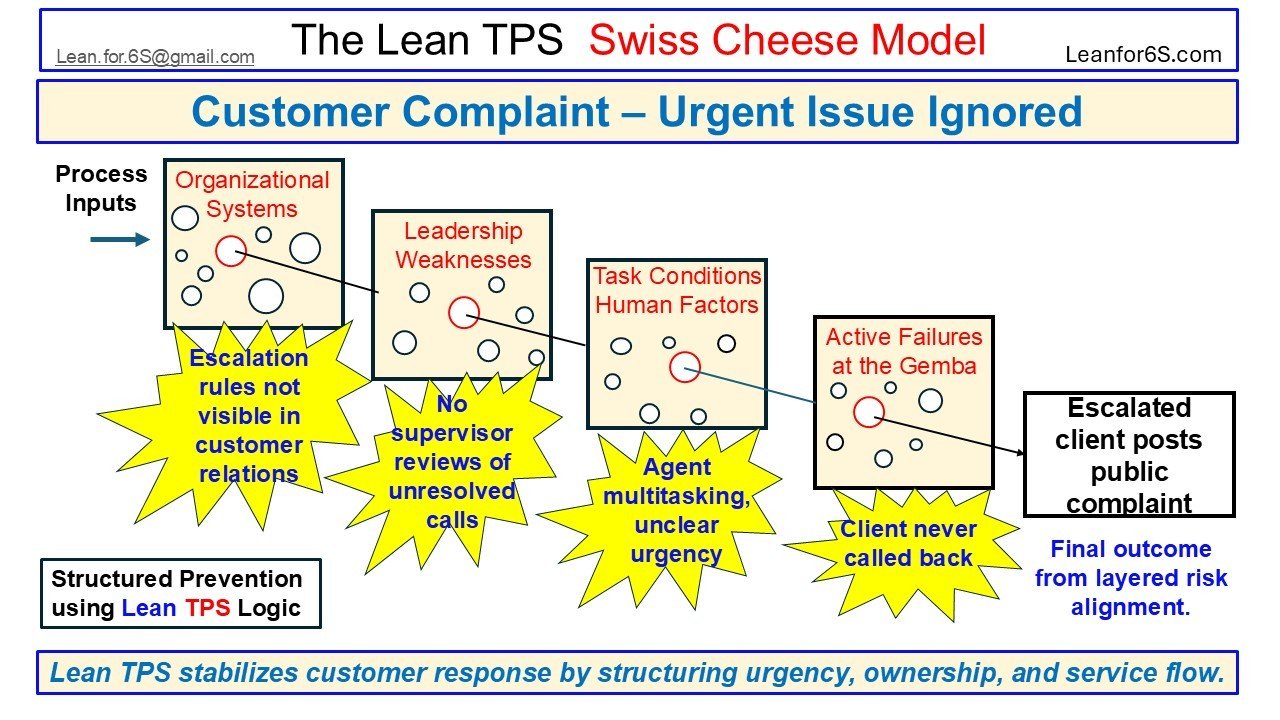

Failure to Escalate Urgent Service Request

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems Escalation rules not visible in customer relations. There was no system in place to flag or highlight unresolved client issues. The escalation logic existed, but it was buried and not accessible to frontline staff.

- Leadership Weaknesses No supervisor reviews of unresolved calls. Supervisors lacked a daily review process to identify stalled or aging cases. Without structured oversight, escalation pathways were missed entirely.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors Agent multitasking, unclear urgency. Agents were managing multiple calls and tasks without clear prioritization. In the absence of urgency indicators, a serious issue was misjudged as routine.

- Active Failures at the Gemba Client never called back. The promised callback was not completed. No confirmation system was in place to ensure closure or follow-through on the request.

Outcome Escalated client posts public complaint. The ignored issue became public, causing reputational harm. The system failed to respond because no layer saw the urgency in time.

Lean TPS Response Make urgency visible. Build structured reviews and escalation clarity into every service process so critical voices never go unheard.

The Customer was left unheard when urgency signals were buried in the system.

This slide reveals how a customer escalation turns into a public complaint when multiple weak layers fail to detect and act on urgency. Despite having systems in place, the failure was not due to a single mistake. It was systemic.

The escalation rules were not visible to frontline staff. There was no structured supervisor review process to flag unresolved or urgent issues. The agent, working under pressure and with unclear instructions, misunderstood the priority. Finally, the customer never received a return call and went public with a complaint.

In Lean TPS, escalation is not reactive. It must be structured, visible, and owned. Response systems must be layered so that urgency is recognized early, not after damage occurs. Escalation protocols must be standardized, with clear accountability at both the team and leadership levels.

This failure was not about one missed callback. It was about the silent absence of ownership, structure, and confirmation. Lean TPS builds service flow that catches urgency before reputational damage spreads.

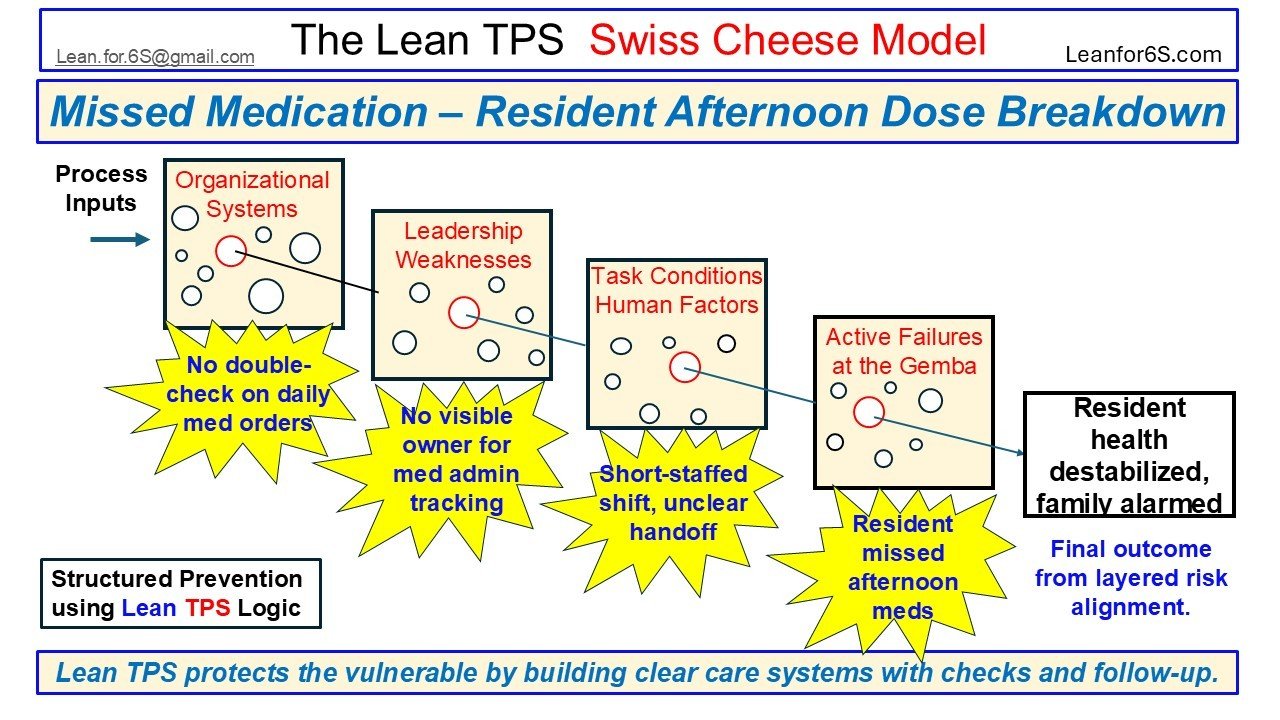

Missed Medication – Afternoon Shift System Failure

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems No double-check on daily med orders. There was no formal second-verification routine to ensure afternoon medications were reviewed. The system relied on informal checks rather than structured confirmation.

- Leadership Weaknesses No visible owner for med admin tracking. No one was assigned clear responsibility for medication flow during the shift. The absence of visible accountability allowed uncertainty and assumptions to spread.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors Short-staffed shift, unclear handoff. Staffing pressures led to rushed transitions and missed communication. The medication task was not handed off with clarity, and timing was compromised.

- Active Failures at the Gemba Resident missed afternoon meds. The medication was never delivered. No system check was in place to alert staff or confirm whether the dose had been administered.

Outcome: A Resident’s health becomes destabilized, and the family becomes alarmed. The missed dose caused visible decline, leading to a concerned family call and deeper scrutiny of the care system.

Lean TPS Response Lean TPS stabilizes health systems by designing visible roles, daily checks, and structured follow-up, so vulnerable people are protected at every step.

Resident misses dose due to unclear shift checks

This scenario illustrates how a missed medication dose in long-term care is not the result of one person’s mistake. It reflects a failure across multiple system layers that are meant to protect vulnerable residents. Each layer had a weakness that silently aligned.

There was no structured double-check in place to confirm daily medication orders. The system relied on informal follow-through. Leadership failed to assign clear ownership for tracking administration. No one was visibly accountable. On the floor, staff worked a short-staffed shift with unclear handoff procedures. Under pressure, the task of delivering afternoon meds was assumed rather than confirmed. At the Gemba, the resident simply did not receive their medication. It was not caught until the resident’s condition began to change and family members raised the concerns.

Lean TPS addresses this kind of breakdown by building structured checks and confirmation into routine care. It supports caregivers with visual control, clear roles, and built-in follow-up. It does not rely on vigilance or memory under stress. The failure here was not about negligence. It was about the absence of systems that make care visible and accountable. When Lean TPS is applied in care environments, small errors are caught before they create harm.

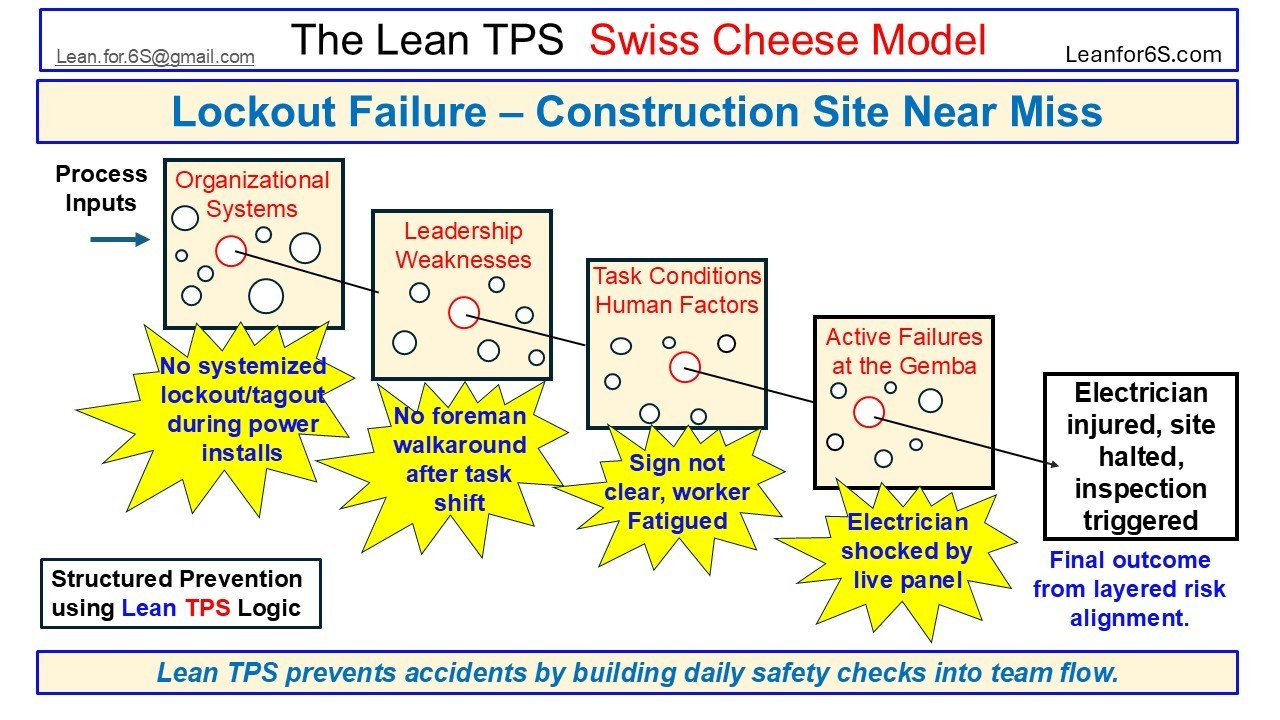

Electrician Shocked by Live Panel During Task Shift

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems No systemized lockout or tagout during power installs. No enforced checklist or procedure ensured power was fully de-energized. The process relied on habit instead of structure.

- Leadership Weaknesses No foreman walkaround occurred after the shift ended. Site status was not reviewed before work resumed. Hazard handoff was left to assumption.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors Fatigue and unclear signage. Crews were stretched thin and visibility was poor. Panel status was misjudged due to rushed work and environmental stress.

- Active Failures at the Gemba Electrician was shocked by a live panel. No lock or sign was in place. Risk passed silently through each layer until contact was made.

Outcome An Electrician was injured and site work was halted. Emergency procedures were activated and a full inspection was triggered.

Lean TPS Response Integrate visual lockout systems, daily walkaround standards, and cross-shift hazard verification into every job site. Safety must be structured not assumed.

An Electrician was injured after a live electrical panel was accessed without lockout or walkaround safety checks. Structured checks were missing at every level.

This slide shows how a serious electrical near miss on a construction site was not caused by a single error, but by multiple silent system failures that aligned. An electrician was injured after contacting a live panel that should have been de-energized. The root issue was not individual negligence, but an absence of structure in how safety was managed.

At the organizational level, there was no formal lockout or tagout system embedded into daily work during power installs. Crews relied on routine habits and informal signals rather than structured confirmation. Leadership made the situation worse by failing to complete a walkaround after the shift ended. No one verified that the area was safe or that power had been cut.

Human factors also played a key role. Workers were fatigued and signage on the panel was unclear. Under time pressure and with limited visual cues, the electrician assumed the circuit was dead. At the Gemba, there were no safeguards in place to stop this error in real time. The result was an electrical shock, halted work, and a triggered inspection.

In Lean TPS, safety is not left to memory or habit. Role-based checks must be built into shift changes, resets, and high-risk tasks. Protecting workers means embedding safety into the flow of work, not hoping someone remembers under pressure.

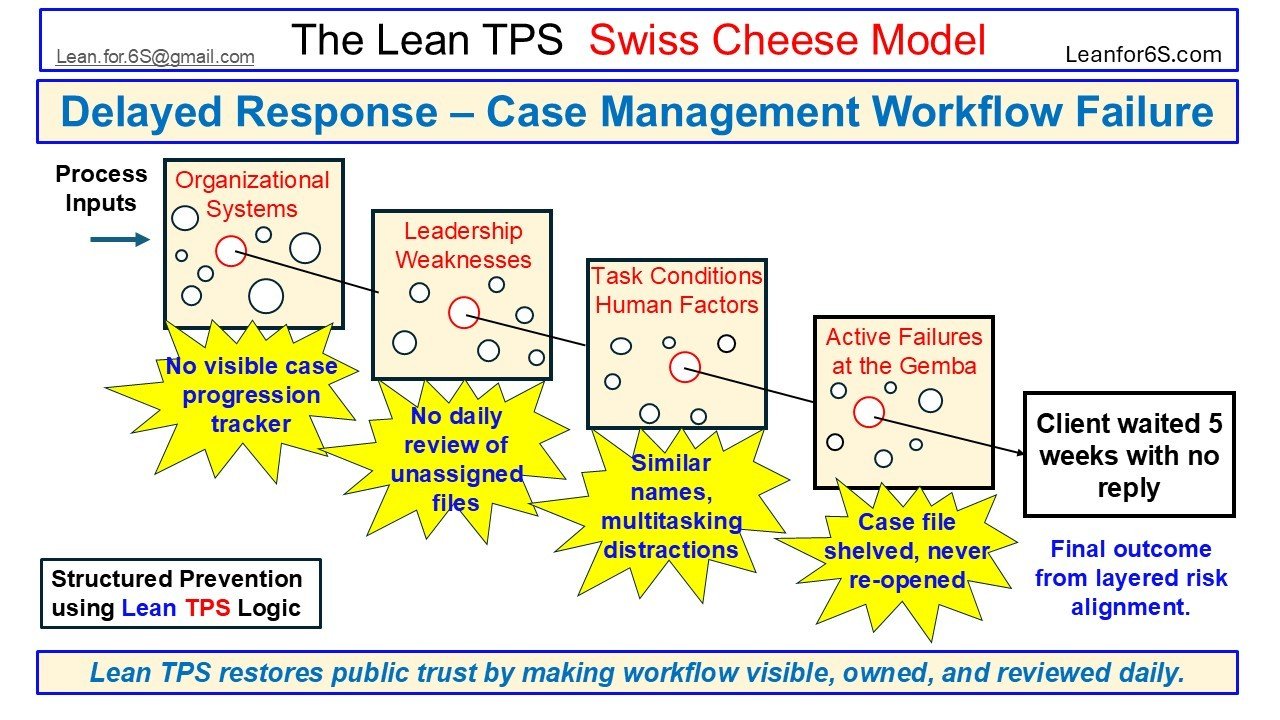

Invisible Ownership – Case Shelved Due to Workflow Drift

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems: No visible case progression tracker. There was no system-level method to surface unprocessed or stagnant files. Without a visual tracker or escalation trigger, stalled cases disappeared into the background.

- Leadership Weaknesses: No daily review of unassigned files. Supervisors did not routinely scan or sort new cases. No one was assigned and accountable for unowned work or backlog status, so unassigned files accumulated quietly.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors: Similar applicant names and multitasking. Staff were managing multiple inputs simultaneously, often toggling between systems. Confusing case identifiers and high task switching increased the likelihood of misplacement.

- Active Failures at the Gemba: Case file shelved and never re-opened. The file was set aside, assumed to be in progress, and never picked back up. The lapse occurred silently at the point of action, with no final check or reminder.

Outcome: The Client waited five weeks with no reply. The client experienced a complete communication failure, damaging trust and reflecting poorly on the organization’s credibility.

Lean TPS Response: Make unowned cases visible, review daily, and assign responsibility with structured follow-up. Lean TPS prevents hidden stagnation by embedding real-time ownership into workflow.

The Client’s case sat untouched for five weeks due to missing visual cues, no ownership, and lack of structured follow-up.

This case illustrates how a simple oversight in case management can quietly grow into a trust-breaking failure. The issue was not one person forgetting. It was a system that allowed a client file to remain untouched for five full weeks without notice.

At the organizational level, there was no visible way to track case progression. Unassigned or delayed cases had no visual signal to surface them. At the leadership level, no supervisor was accountable for reviewing stagnant files. Without daily review routines or dashboards, the backlog grew silently.

Task conditions made the situation worse. Agents were multitasking across platforms with similar case names and no structured handoff process. In the noise of daily work, the file was shelved and never re-opened. No one noticed until the client escalated.

This is not a failure of care. It is a failure of system design. Lean TPS ensures that no file goes dark by embedding case visibility, ownership, and daily flow review into routine work. The solution is not a reminder. It is a structure that makes delay visible before damage occurs.

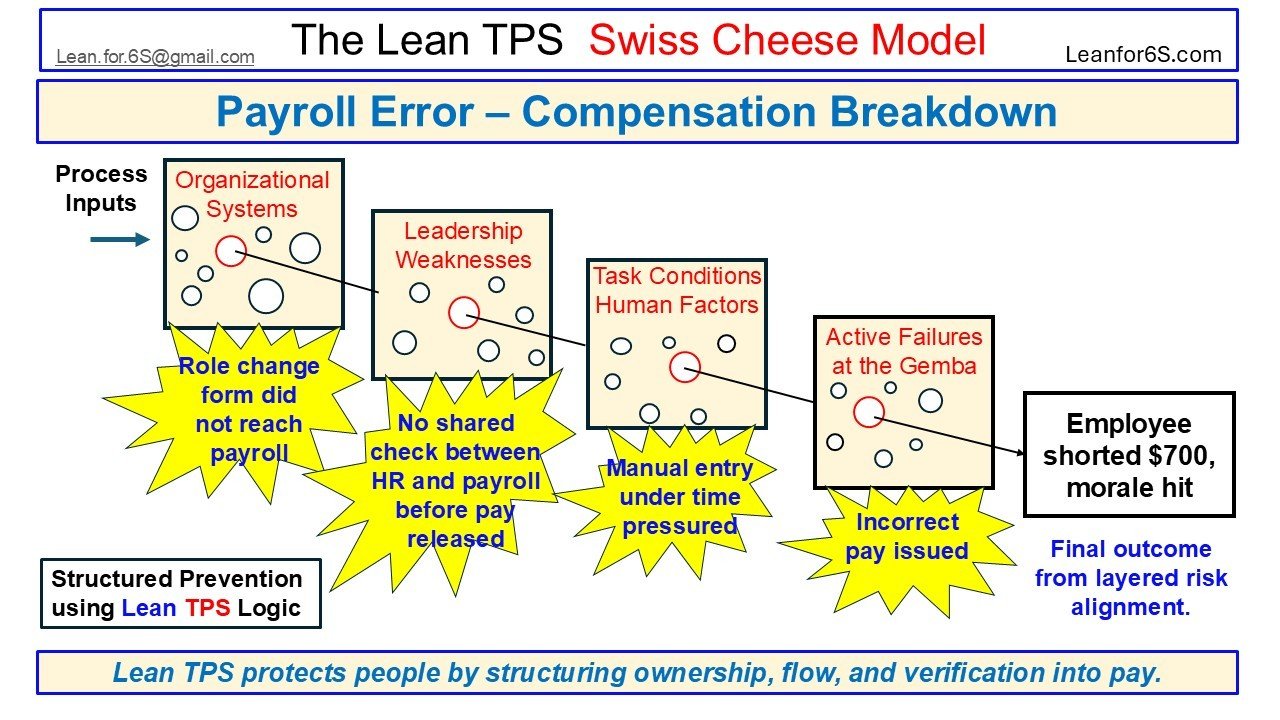

Invisible Pay Ownership – Role Change Not Verified

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems: Employee Role change form did not reach payroll. No structured handoff or digital confirmation existed to ensure updated pay information was received.

- Leadership Weaknesses: No shared verification step between HR and payroll before releasing pay. Leadership assumed the update had been processed without confirming it.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors: Manual data entry occurred under time pressure. The processor had no visual alert or review buffer to detect the error.

- Active Failures at the Gemba: Pay was released based on outdated information. The employee received less than they were owed.

Outcome: Employee was shorted $700, resulting in frustration and morale impact.

Lean TPS Response: Lean TPS builds verification into the system itself. Role changes must trigger visible confirmation, and pay must not be released until responsibility is confirmed by both HR and payroll.

Role update never reached payroll and no one confirmed pay was released in error.

This payroll failure was not caused by a single error in judgment. It was the result of a layered breakdown in system visibility, leadership accountability, and cross-functional flow. An employee received a promotion and submitted a role change form. But the form never reached payroll. No one noticed.

At the organizational level, there was no system to track or confirm receipt of compensation updates. The leadership layer failed to establish a shared HR and payroll review process before funds were released. Manual entry, performed under deadline pressure, further increased the likelihood of error. By the time payroll was issued, the employee’s correct rate had never been applied.

The outcome was more than just a paycheck mistake. The employee was shorted seven hundred dollars. Confidence in the organization took a hit. Trust is not measured only by how well people are paid, but by how reliably systems uphold fairness.

Lean TPS does not blame the person entering the data. It asks why there was no stopgap to confirm changes. It builds verification into the process itself. Pay must be structured like any other critical process visibly tracked, jointly owned, and validated before impact reaches the employee. In Lean TPS, respect for people begins with how we manage their pay.

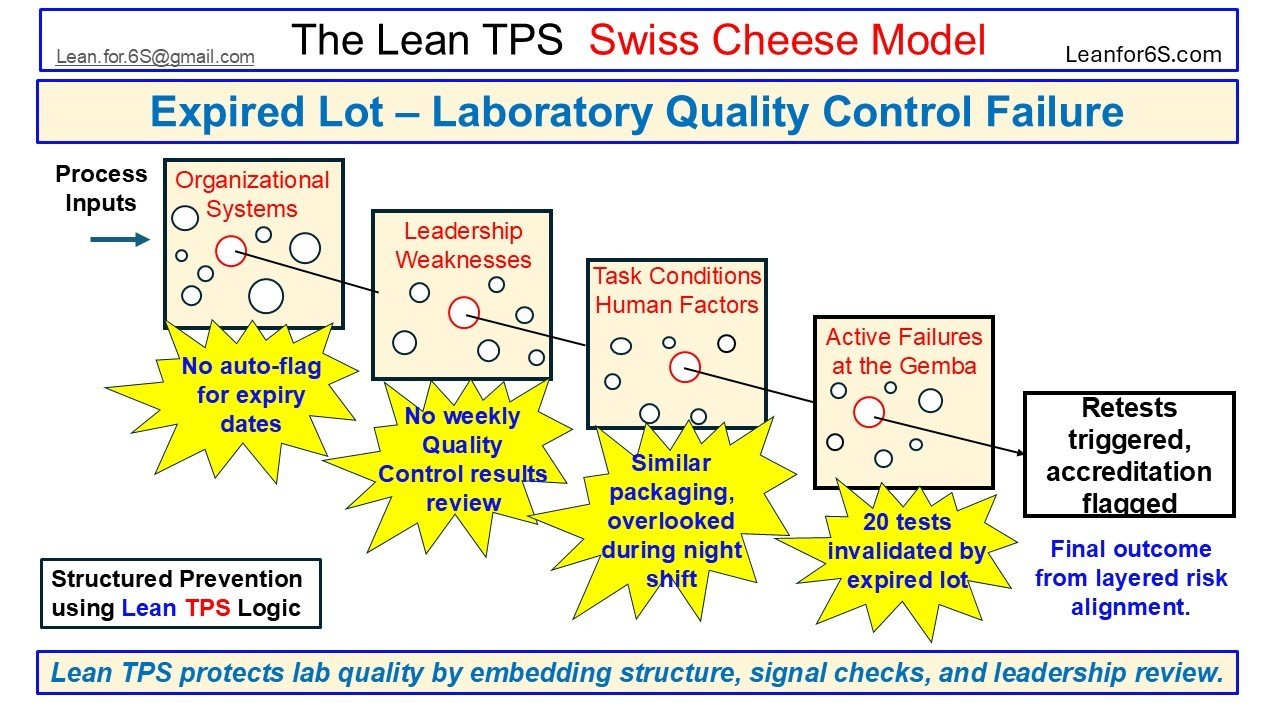

Expired Lot – Laboratory Quality Control Failure

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems: No auto-flag for expiry dates. There was no automated control to alert staff when test materials were expired. The system quietly allowed outdated lots to remain in use.

- Leadership Weaknesses: No weekly Quality Control results review. Leadership failed to maintain a routine cadence for monitoring quality signals, allowing issues to go undetected.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors: Similar packaging during night shift. Fatigued staff working overnight were unable to distinguish visually between valid and expired lots.

- Active Failures at the Gemba: Twenty tests were completed using expired materials. The problem was only discovered after results had already been issued.

Outcome: Retests were triggered and external accreditation was flagged. This created compliance risk and required costly rework.

Lean TPS Response: Lean TPS embeds structure into daily reviews, visual expiration checks, and leader-driven quality confirmation. It does not rely on memory or alertness. It ensures quality risks surface before reaching patients.

Expired reagents used during night shift; 20 lab tests invalidated and flagged in accreditation review.

This laboratory failure was not caused by a careless technician. It was the result of multiple silent breakdowns that aligned across time. Twenty tests were completed using expired reagents. By the time the issue was discovered, results had already been delivered and accreditation was at risk.

The problem began with the lack of an auto-flag system for expiry dates. There was no structured alert to warn staff that the lot was outdated. Leadership did not conduct weekly Quality Control reviews, which meant early signs of material risk went unacted. During the night shift, similar packaging made it easy to confuse old and current lots. Fatigued technicians, trying to maintain flow, relied on visual cues that were unclear. Standard work existed, but safeguards were not embedded into the process.

Lean TPS addresses this through structure, not blame. It introduces expiry verification, weekly quality reviews, and clear identification of the escalation flow so that latent risks are seen before harm occurs. It protects patients by reinforcing the system, not the vigilance of the individual. Accreditation and trust are not built on good intent alone. They are earned by designing systems that prevent these lapses from ever reaching the test bench.

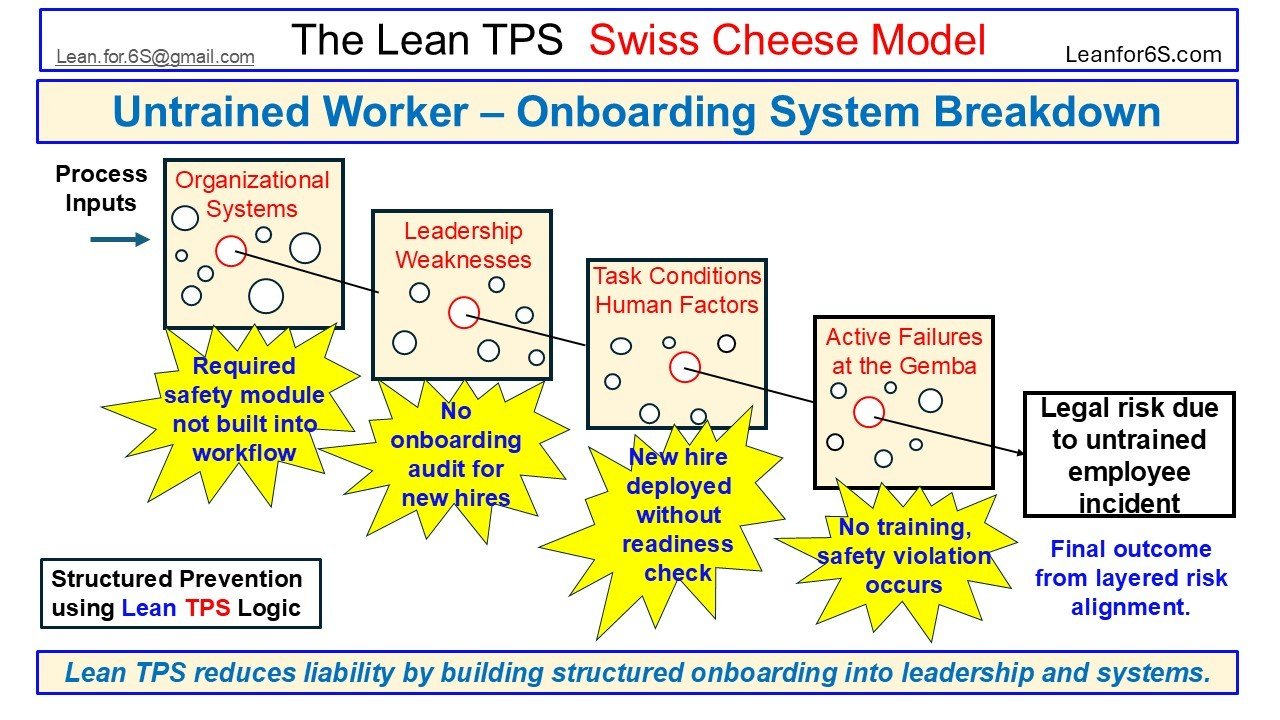

Untrained Hire – Safety Module Skipped in Onboarding

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems: Required all safety module was not embedded in the onboarding workflow. There was no system checkpoint to ensure safety training occurred before job duties began.

- Leadership Weaknesses: No onboarding audit was conducted for new hires. Leaders assumed training was complete without crosschecking records or confirming readiness.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors: Due to staff shortages or urgency, the new employee was assigned to frontline duties without completing mandatory preparation. Pressure to fill gaps outweighed safety readiness.

- Active Failures at the Gemba: A safety violation occurred when the untrained worker acted without proper instruction. The incident exposed a training gap, not a behavioral one.

Outcome: Legal liability was triggered when the incident revealed the employee had not completed the mandatory training.

Lean TPS Response: Embed onboarding confirmation into leadership workflow. Lean TPS uses visual tracking, system triggers, and role-based audits to ensure every employee is trained before risk exposure.

Untrained employee who caused incident after serious onboarding gaps.

This onboarding failure did not start with the employee. It started with the absence of structure. A new hire was brought into a safety-sensitive role without completing mandatory training. The safety module existed but was not integrated into the standard onboarding process. No leader confirmed it was done. No system checkpoint flagged the gap. And under pressure to staff the floor, the worker was rushed in.

The incident that followed triggered more than just internal concern. It raised legal exposure and public credibility questions. Yet no single person failed. The system did.

In Lean TPS, onboarding is not HR’s responsibility alone. It is a shared process owned by leadership. Visual controls, confirmation steps, and built-in escalation points ensure no one enters the workplace unready.

The Swiss Cheese Model helps us see what was missing. At the system level, the safety requirement was invisible. At the leadership level, no audit confirmed it. Human factors like urgency or goodwill overrode caution. And at the Gemba, the violation occurred not from defiance, but from lack of preparation.

Lean TPS designs training into the flow. It assigns ownership, confirms readiness, and treats onboarding as the first act of care. Not doing so invites risk, not just to people, but to the organization’s integrity.

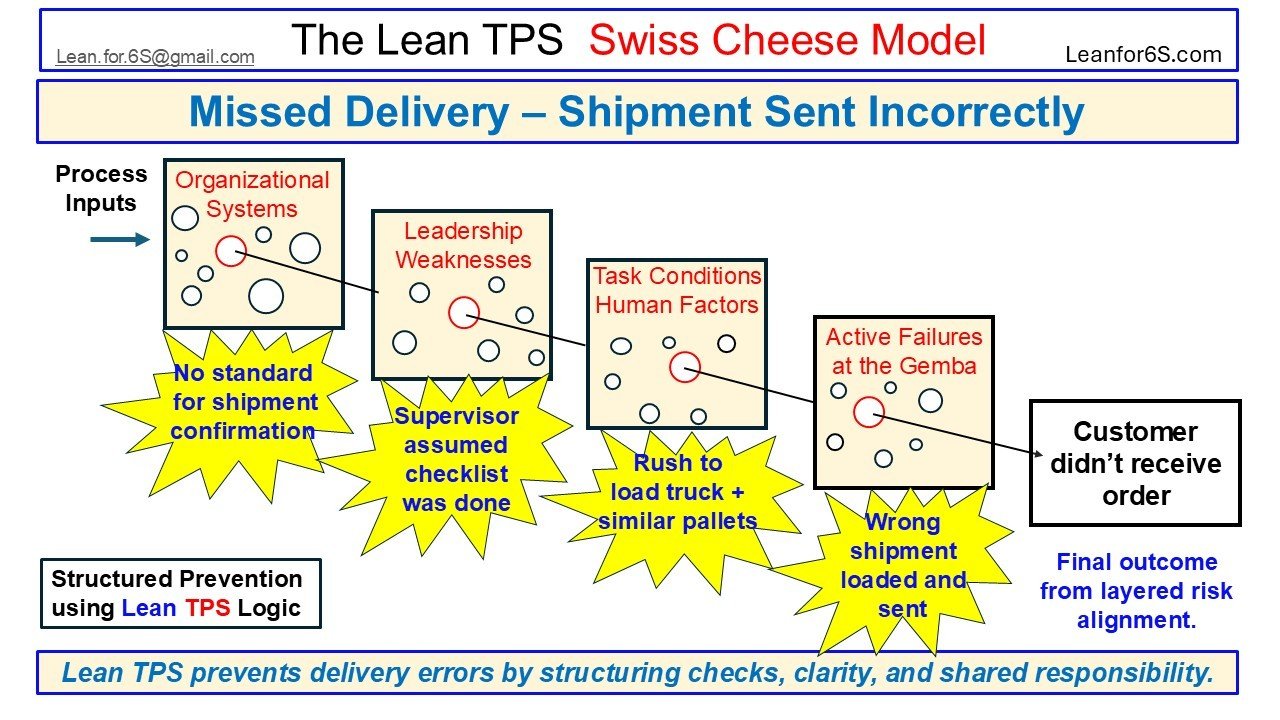

Invisible Shipment Check – Delivery Sent Without Verification

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems No standard for shipment confirmation. There was no formal process to verify shipments before departure. Shipment confirmation was left to informal habits, without a documented checklist, barcode scan, or visual validation step.

- Leadership Weaknesses Supervisors assumed check list was done. There was no direct verification of completion. Supervisors did not confirm the shipment’s accuracy, relying instead on verbal assurance or assumption under pressure.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors Rush to load trucks and similar pallet appearance. Loading occurred under time constraints, and pallets looked nearly identical. Labeling was unclear, and workers under stress defaulted to assumptions rather than confirmations.

- Active Failures at the Gemba Wrong shipment loaded and sent. The incorrect shipment was loaded onto the truck and dispatched. No final confirmation step was built into the process flow.

Outcome Customer didn’t receive an order. The error was only discovered after delivery failed, causing delays, frustration, and customer dissatisfaction.

Lean TPS Response Structure layered shipment verification with defined ownership and time for confirmation. Lean TPS prevents errors not by extra effort, but by embedding checks where failure occurs.

Shipment was sent without confirmation due to rushed loading and unclear responsibility.

This shipment failure was not caused by a single oversight. It was the result of missing structure at every level. The organization had no defined process to verify shipment accuracy before the truck left. There was no visual confirmation, no barcode check, and no documented standard for outbound verification.

Supervisors assumed the checklist had been completed, but no one confirmed it directly. At the task level, workers faced pressure to load quickly, and the pallets looked nearly identical. Without clear labeling or structured time for confirmation, the wrong load was selected.

When the truck departed, there was no second chance. The error traveled with it, reaching the customer as a missing delivery. The failure was discovered only after the damage was done.

Lean TPS addresses this not by asking people to try harder, but by building layered safeguards into the flow of work. Shipment confirmation must be visible, owned, and expected as part of the routine not left to chance or assumption. Teams need shared responsibility, real-time feedback, and time built into the process for final checks. That is how delivery becomes reliable because trust begins at the dock.

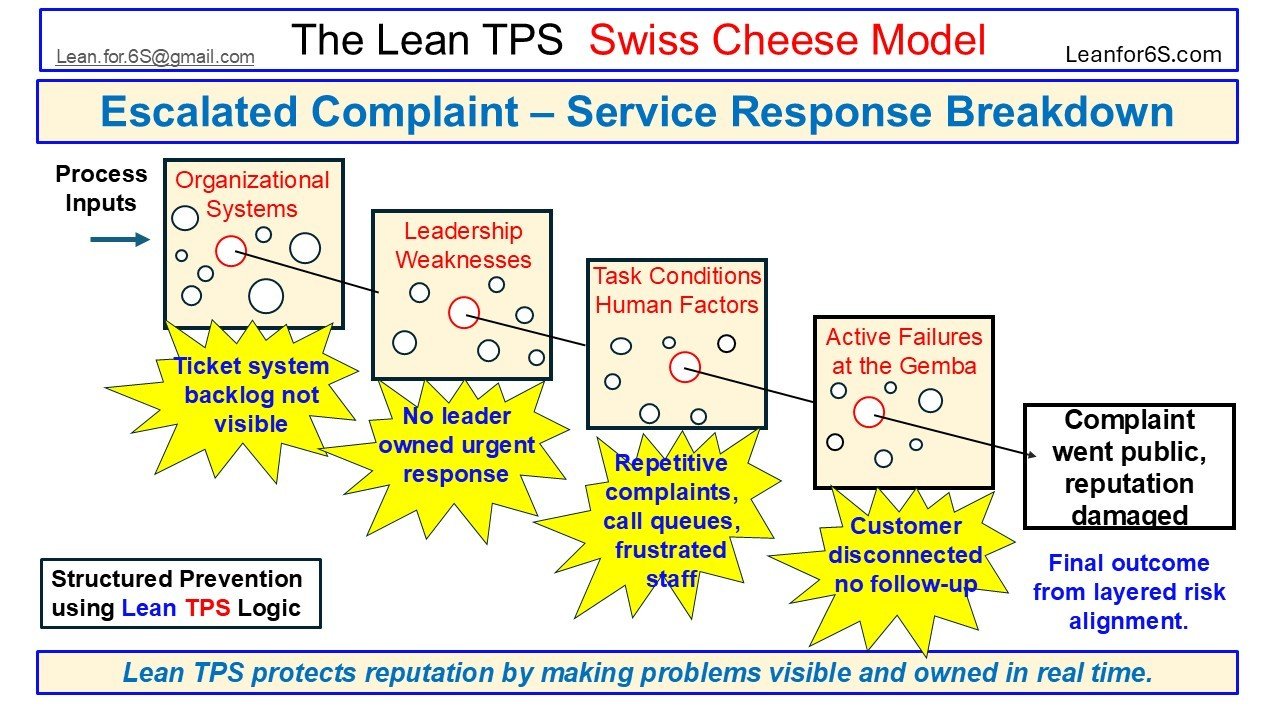

Escalated Complaint – Urgent Case Went Unseen

Systemic Risk Breakdown

- Organizational Systems The Ticket system backlog was not visible. The service platform lacked visual controls or dashboards showing overdue or unresolved issues. Urgent items remained hidden among the routine items, and there was no trigger for escalation.

- Leadership Weaknesses No leader assigned to own urgent responses. No single person was responsible for identifying or owning priority tickets. Responsibility was diluted, and no structured response routine existed to flag risk early.

- Task Conditions – Human Factors Repetitive complaints, call queues, frustrated staff. Frontline staff were stuck in reactive mode, handling high volumes with little clarity on priorities. Fatigue, repetition, and emotional strain made real-time judgment difficult.

- Active Failures at the Gemba Customer disconnected without follow-up. Despite multiple contacts, the issue went unresolved. The final call failed to close the loop or reassure the customer. They left feeling ignored and took their complaint elsewhere.

Outcome: A Complaint went public, reputation was damaged. What started as a fixable service problem became a public issue. The company’s credibility took the hit because no layer caught it in time.

Lean TPS Response Build visibility, leadership ownership, and structured escalation into the system. Lean TPS protects customer trust by ensuring problems are surfaced, owned, and addressed before customers give up.

A Customer issue was ignored with no follow-up, and it went public.

This case shows how a preventable service failure can snowball into public fallout when responsibility is unclear and system signals go unseen.

The problem began quietly. The ticket system had no visual backlog indicator or escalation flag. Urgent cases blended in with routine ones. No structured system highlighted which customers were still waiting. At the leadership level, no one was assigned to monitor unresolved complaints. Without daily ownership, there was no trigger to act early.

Frontline staff were overwhelmed. They fielded repeated calls from the same customer but had no clear view of issue priority or customer sentiment. Frustration built on both sides. Eventually, the customer disconnected. No one followed up. They felt abandoned and they shared it publicly.

Lean TPS does not treat escalation as a reactive firefight. It treats it as a structured daily discipline. Problems must be made visible. Urgent cases must be clearly owned. And leaders must act before the customer walks away.

TPS protects reputation not by hiding issues, but by surfacing them early and assigning ownership before harm is done. This is not a story about one missed call. It is a story about a system that left a customer behind.

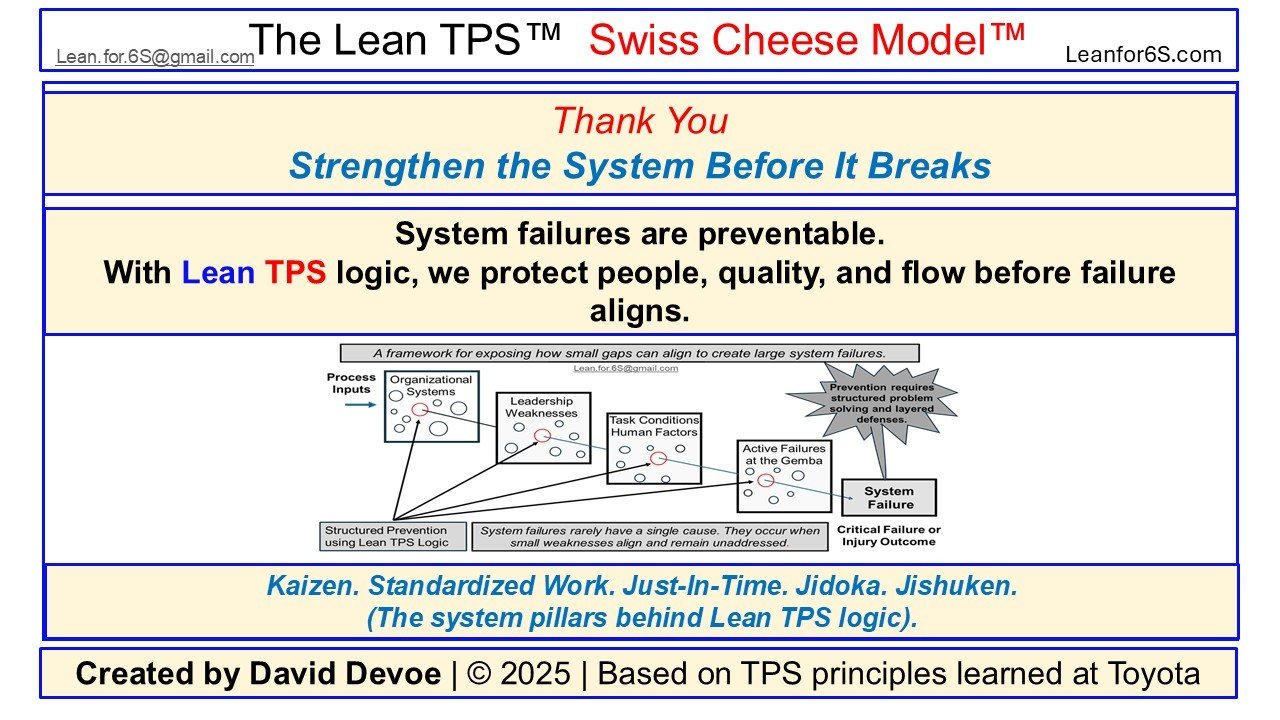

Final Reflection: Strengthen the System Before It Breaks

This final case brought us full circle. What looked like a customer complaint was, in fact, a breakdown in system visibility, leadership ownership, and frontline response. But more importantly, it revealed what Lean TPS has always taught: most failure, is not sudden. It is the result of small risks quietly aligning.

This is where the Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model™ delivers its greatest value. It is not just a diagnostic. It is a leadership tool for prevention.

Let’s take one last look at the full model and its purpose then close with how you can use it to build stronger systems starting today.

Lean TPS protects people, quality, and systems by strengthening flow before failure occurs.

Final Reflection: Strengthen the System Before It Breaks

This final slide brings the full purpose of the Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model™ into focus. It is not just a tool or visual aid. It is a structured way to see how silent gaps, often invisible, can align into failure unless leaders act before the harm is done.

In traditional problem solving, too many teams focus on the last visible error. They react to the surface issue but miss the deeper layers upstream. Lean TPS logic reframes that mindset. It teaches us to see system failures not as isolated mistakes, but as preventable outcomes of layered weaknesses—structural, cultural, and operational.

Across the examples shared in this article, the same pattern emerged. The problem was never one person, one task, or one gap. It was the quiet alignment of unchecked risks across four levels: organizational systems, leadership behavior, task conditions, and frontline execution.

The Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model™ exists to help teams make those risks visible—before they become real.

With Kaizen, Standardized Work, Just-In-Time, Jidoka, and Jishuken, we build in clarity, structure, and shared responsibility. We replace assumption with confirmation. We protect trust with process. And we prevent rework, harm, or regret by reinforcing the system before it fails.

This thinking is not limited to one industry. It applies anywhere people and systems interact—healthcare, education, construction, logistics, technology, finance, and beyond.

Lean TPS protects people, quality, and systems by strengthening flow before failure occurs.

Thank you for exploring this model. Now let’s go build stronger systems, together.

If this article resonated with your experience, I welcome your thoughts or questions in the comments. Let’s keep improving the system together.

– David Devoe, Creator of the Lean TPS Swiss Cheese Model™

To learn more about structured learning inside Lean TPS, visit the 5S Thinking Series and the Jishuken page.

5S Thinking Series

→ https://leantps.ca/5s-thinking-series/

Jishuken

→ https://leantps.ca/jishuken/

For foundational TPS terminology, see the official Toyota Industries Corporation overview: https://www.toyota-industries.com/