Standardized Work as the Foundation of Quality and Stability

1. Why Lean TPS Standardized Work is the only system capable of supporting Mixed Model Human–Humanoid production

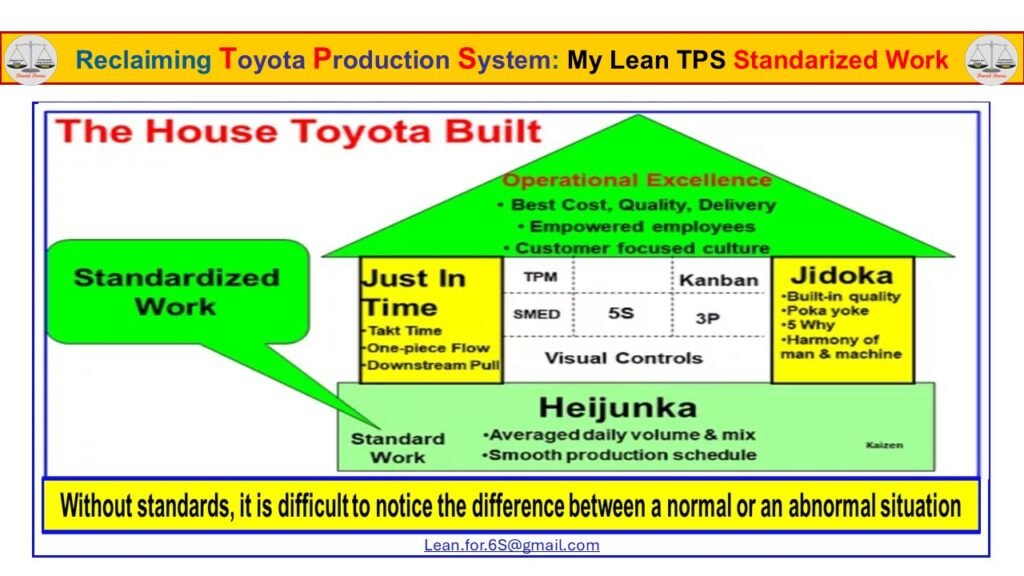

Figure 1. The House Toyota Built – Standardized Work as the Foundation

Standardized Work establishes the foundation required to protect Quality and maintain operational stability.

The Foundation That Makes Normal Visible

The Toyota Production System was not designed to optimize machines. It was designed to define normal so Quality could be protected in complex, variable environments. That purpose becomes even more critical as work moves beyond human-only execution and into Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid environments where ambiguity, informal judgment, and silent compensation can no longer be relied upon.

For decades, organizations have depended on people to absorb variation. When conditions were unclear, humans adjusted. When work deviated, people compensated. When problems occurred, they were often fixed locally and passed forward without full understanding. This worked only because human judgment filled the gaps left by weak systems.

That assumption no longer holds.

Humanoid robots are being designed to operate in the same physical spaces as humans. They share human height, reach, and motion for a reason: to function in homes, offices, and plants built for people. But unlike humans, humanoids cannot interpret intent, tolerate ambiguity, or safely improvise when conditions are not clearly defined. They will execute exactly what they are trained to do and continue operating unless explicitly instructed to stop.

This is where Standardized Work becomes non-negotiable.

Standardized Work is not documentation. It is not a checklist. It is the disciplined definition of the current best method to perform work safely, repeatedly, and in sequence. It establishes a shared understanding of what normal looks like, how work should progress, and how deviations must be handled. Without this definition, there is no reliable way to distinguish between normal and abnormal conditions, and no stable reference from which learning or improvement can occur.

In Lean TPS, Standardized Work forms the foundation that supports Just-in-Time, Jidoka, and Heijunka. Flow, built-in Quality, and levelled production all depend on work being performed in a known sequence at a known pace, with clear expectations for response when conditions change. This foundation allows systems to remain flexible without becoming unstable, even in high-mix, small-lot environments.

Most importantly, Standardized Work shifts responsibility from individuals to the system. When work is clearly defined, anyone can recognize when conditions are not normal. Problems are no longer hidden by personal judgment or experience. They become visible signals that require action, investigation, and learning. This discipline is what allows organizations to protect Quality while adapting to change.

As humanoids become integrated into everyday work, the need for this clarity increases. Training a humanoid is not programming a generic machine. It is teaching work as it is performed in a specific environment, with specific risks, constraints, and Quality expectations. Without Standardized Work, that training will simply reproduce variation, embed poor practices, and scale instability.

The House Toyota built endures because it was designed for instability, not perfection. Standardized Work is the foundation that allows people, machines, and eventually humanoids to operate together safely by making normal visible, abnormal unmistakable, and learning unavoidable.

2. The Three Basic Elements of Standardized Work

Why Lean TPS defines takt, sequence, and work-in-process as inseparable conditions for Quality

Standardized Work in Lean TPS is not created by documents or charts. It is created by defining the minimum conditions required for work to remain stable and predictable. These conditions are expressed through three basic elements that must exist together. This section establishes why Lean TPS treats these elements as a single system rather than independent concepts and why Quality cannot be protected when any one of them is missing.

Figure 2. The Three Basic Elements of Standardized Work

Takt time, standardized work sequence, and standardized work-in-process define the minimum conditions required to protect Quality and maintain stable flow.

Standardized Work only functions when all three elements exist together

Standardized Work in Lean TPS is built on three basic elements that must be defined together. These elements are not tools and not optional components. They establish the minimum operating conditions required for a process to remain stable and for Quality to be protected consistently. When any one of these elements is missing or weak, Standardized Work collapses and the system reverts to variation driven by individual judgment rather than method.

The first element is takt time. Takt time defines the pace required to meet customer demand by establishing how much time is available to complete one unit of work. Without takt time, there is no objective reference for determining whether work is being performed too fast, too slow, or unevenly. Operators are forced to self-pace based on experience, which increases overburden and hides Quality risk. In Lean TPS, takt time serves as the external constraint that aligns all work to demand and exposes imbalance immediately.

The second element is standardized work sequence. Sequence defines the precise order in which tasks are performed. This order is selected as the safest, most repeatable method known at the time. When sequence is not defined, individuals naturally develop personal work patterns. These differences mask variation and make it impossible to distinguish normal from abnormal conditions. A defined sequence allows leaders to observe work accurately, verify adherence, and identify deviation before defects occur.

The third element is standardized work-in-process. This defines the minimum amount of material required to maintain continuous flow between process steps. Too little work-in-process causes starvation and interruption. Too much hides problems and delays detection of abnormality. Standardized work-in-process is not inventory. It is a deliberately set condition that supports flow at takt time and exposes instability immediately when the standard is violated.

These three elements are inseparable. Takt time establishes pace. Sequence defines how work is performed. Work-in-process sustains flow between steps. Defining only one or two creates a false sense of control while allowing Quality risk to accumulate unnoticed. Lean TPS treats these elements as a single system because stability cannot be achieved any other way.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, this structure becomes non-negotiable. Humans and humanoid robots must operate to the same takt logic, follow the same sequence intent, and rely on the same in-process conditions. Any ambiguity in pace, order, or handoff creates immediate safety and Quality risk. The three basic elements of Standardized Work provide the shared operating language that allows mixed systems to function safely and predictably.

This section establishes the logic that governs all Standardized Work that follows. Every chart, worksheet, and visual control used in Lean TPS exists to define, confirm, or improve one or more of these three elements. Without them, Standardized Work cannot protect Quality or support sustained improvement.

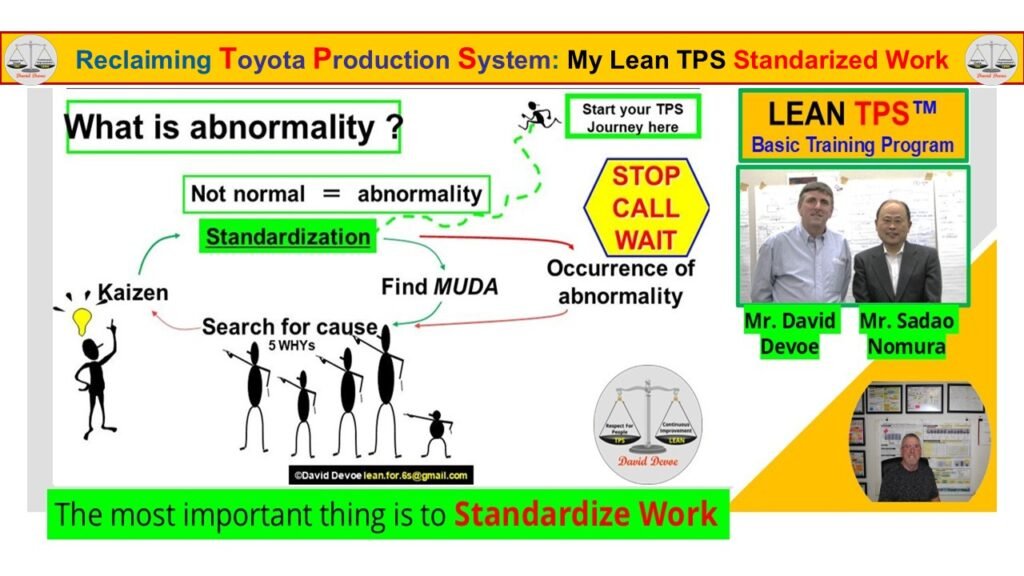

3. Standardized Work as the Baseline for Kaizen

Why Lean TPS treats improvement as impossible without a defined standard

Kaizen is often misunderstood as the act of improving work. In Lean TPS, kaizen begins much earlier. It begins by defining the current method clearly enough that normal and abnormal can be distinguished. This section explains why Standardized Work is not the result of kaizen, but the condition that makes kaizen possible and why Quality improvement cannot occur without it.

Figure 3. Standardized Work as the Baseline for Kaizen

Standardized Work defines the current condition so abnormalities can be seen and improvement can be verified and sustained.

Improvement cannot be confirmed without a standard

Standardized Work is the base for all kaizen activity in Lean TPS. Without a defined standard, it is impossible to determine whether a change represents an improvement or simply another variation. When work is performed differently by each operator or each shift, results fluctuate and problems appear random. Quality issues are treated as isolated events rather than signals of system weakness.

The purpose of Standardized Work is to document the current situation. This does not mean documenting how work should be done in theory. It means capturing how the work is actually performed at the gemba, under real conditions, with real constraints. This documented method becomes the baseline. Once the baseline is clear, leaders and operators can recognize when work deviates from normal and investigate why.

When kaizen is applied, changes are made deliberately against this baseline. If the change reduces variation, improves flow, or strengthens Quality, it is verified through observation. Only after verification does the improved method become the new standard. This discipline prevents regression and ensures that improvements are held rather than lost over time.

As standards improve, new standards replace old ones. Each new standard becomes the baseline for the next cycle of improvement. This is why Lean TPS describes Standardized Work as a living system. It evolves as learning occurs, as conditions change, and as better methods are discovered. Improvement does not stop, but it never proceeds without a clear reference point.

This logic is especially critical in Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production. In these environments, small deviations in sequence, timing, or handoff can quickly escalate into Quality or safety risk. Without a clearly defined standard, there is no way to confirm whether a change has reduced risk or introduced new instability. Standardized Work provides the shared reference that allows both humans and machines to improve together without increasing variation.

Standardized Work does not limit improvement. It enables it. By defining normal, it makes abnormal visible. By capturing the current condition, it allows improvement to be measured. This is why Lean TPS treats Standardized Work as the starting point of kaizen and why Quality improvement cannot be sustained without it.

4. Standardized Work Tools Make Abnormalities Visible

How Lean TPS uses visual methods to protect Quality and sustain improvement

Lean TPS relies on a small number of disciplined visual tools to make the work method visible. These tools do not exist to document activity or support reporting. They exist to define normal conditions clearly enough that abnormality can be detected immediately. When the method is visible, Quality risk surfaces early and improvement becomes factual rather than opinion based.

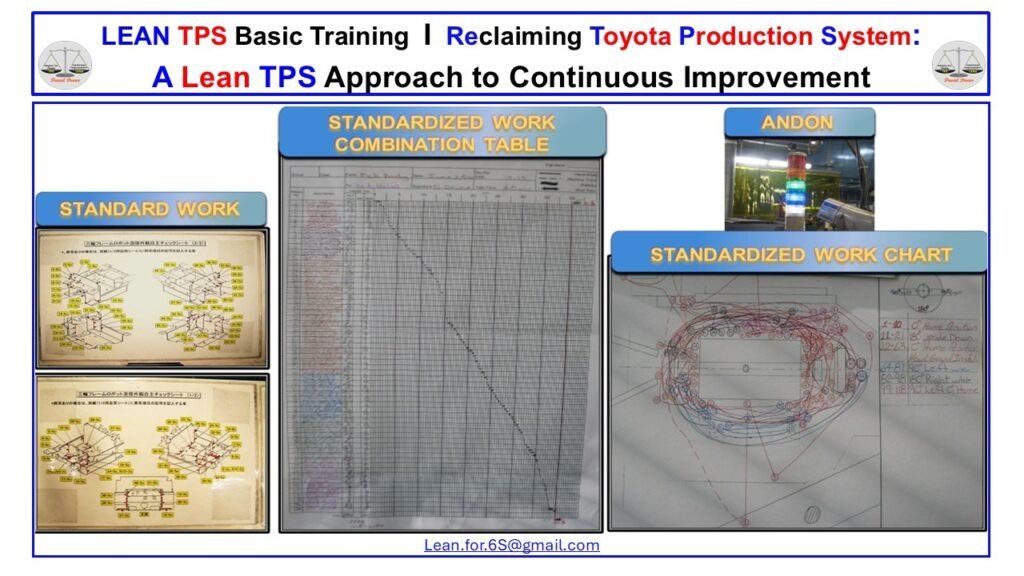

Figure 4. Standardized Work Tools Supporting Continuous Improvement

Standardized Work charts, combination tables, and Andon define normal conditions so abnormalities can be detected, responded to, and corrected before Quality is compromised.

Standardized Work tools exist to expose deviation, not to record activity

Standardized Work tools translate the defined method into something that can be observed, confirmed, and corrected at the gemba. Without this visibility, leaders and operators are forced to rely on memory, habit, or interpretation. That condition hides variation, delays response, and allows Quality risk to accumulate unnoticed.

The Standardized Work Chart defines the physical layout, work sequence, and operator movement. It shows where work is performed and how people, materials, and tools interact. When actual movement or sequence differs from what is defined, the deviation becomes visible immediately. This allows leaders to determine whether instability originates from layout, sequence design, or material presentation rather than reacting after defects occur.

The Standardized Work Combination Table makes the relationship between manual work, walking, and machine time visible against takt. It shows whether the work content fits within the required pace and where imbalance exists. When work exceeds takt or is unevenly loaded, the gap is exposed. This visibility protects Quality by revealing overburden, waiting, and hidden waste before they result in defects or missed delivery.

Andon completes the system by providing a direct response mechanism. When work cannot be performed to standard, the abnormal condition must be signaled immediately. Andon is not a productivity tool. It is a Quality protection mechanism. It enables stop, call, and wait so support can arrive and the standard can be restored before defects move downstream.

Together, these tools form a closed loop. Standardized Work defines normal. Visual tools make the method observable. Andon enables immediate response. When used correctly, problems are not absorbed by individuals and improvement remains disciplined rather than reactive.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, this visibility becomes essential. Humans and humanoid robots must rely on the same defined method and the same signals of abnormality. Visual tools provide a shared reference that allows both to operate safely at takt. Without this clarity, deviation cannot be detected in time and Quality risk escalates rapidly.

Standardized Work tools do not create stability by themselves. They support stability by making deviation unmistakable. Their value lies in how clearly they expose abnormal conditions and how consistently leaders respond. This is why Lean TPS limits the number of tools and insists they be used for confirmation, not decoration.

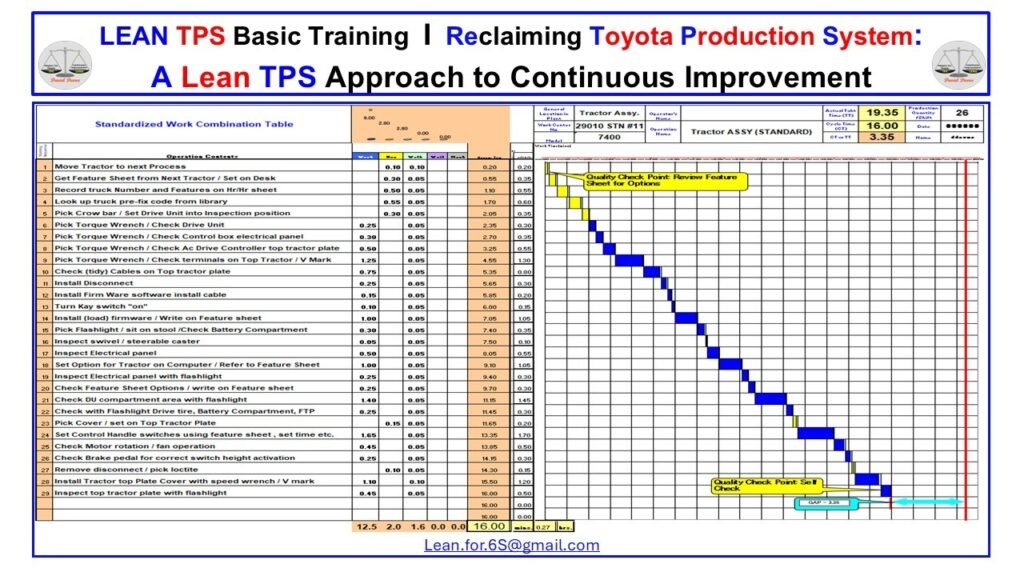

5. The Standardized Work Combination Table Aligns Work to Takt

Why Lean TPS uses time based visualization to protect Quality and expose imbalance

Standardized Work must do more than describe what tasks are performed. It must confirm whether the work can be executed within takt time under real conditions. The Standardized Work Combination Table exists for this purpose. It makes the relationship between manual work, walking, and machine time visible so imbalance and overburden are exposed before Quality is compromised.

The combination table converts Standardized Work from intent into proof. It shows whether the defined sequence fits within the required pace and where instability is being introduced. Without this time-based confirmation, work may appear acceptable while hidden delays, overload, or waiting quietly erode Quality.

Figure 5. Standardized Work Combination Table Aligned to Takt

The combination table visualizes manual work, walking, and machine time against takt so imbalance and overburden can be identified and corrected.

From defined sequence to verified execution

The Standardized Work Combination Table plots each element of the work sequence against time. Manual work, walking, and machine cycles are shown together so their interaction can be understood as a system rather than as isolated tasks. When the plotted line exceeds takt time, the abnormal condition is visible immediately. This prevents Quality from being protected only by individual effort or informal workarounds.

The table also reveals uneven loading within the sequence. Clusters of manual work, excessive walking, or poorly synchronized machine cycles become obvious when viewed against time. These conditions often remain hidden when work is described only through lists or charts that lack a time dimension. The combination table forces the system to confront whether the work is realistically balanced.

Quality checkpoints are deliberately positioned within this time-based structure. Inspection and verification steps are not added as separate activities. They are placed where they can be executed without disrupting flow or creating overburden. This ensures Quality is built into the work rather than inspected after defects occur.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, this confirmation becomes critical. Humans and humanoid robots must operate within the same takt window. Any mismatch between human motion, robot cycle time, or machine availability immediately creates Quality and safety risk. The combination table provides a shared reference that allows both human and machine work to be synchronized deliberately.

The Standardized Work Combination Table is not a planning document. It is a confirmation tool. It answers a single critical question: can this work be performed to standard, at takt, without overburden or instability. When the answer is no, the problem is visible and improvement can begin.

This is why Lean TPS treats the combination table as essential. It protects Quality by exposing imbalance early and prevents improvement from being driven by assumption rather than fact.

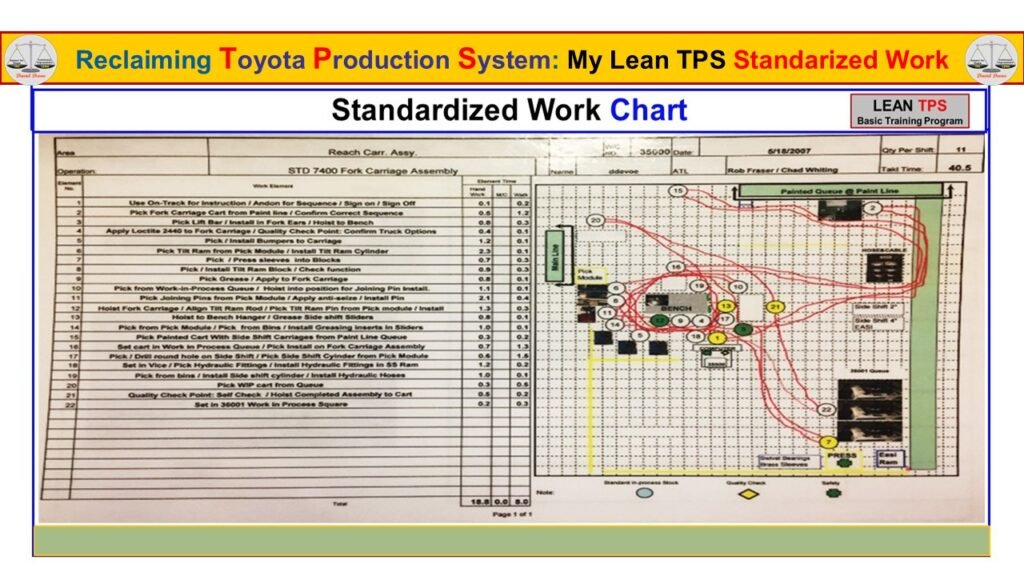

6. The Standardized Work Chart Defines Sequence and Motion

Why Lean TPS makes work observable in space, not just time

Standardized Work must be visible in the physical workplace. Describing tasks or listing steps is not sufficient to protect Quality. Lean TPS requires the work sequence, movement, and interaction with equipment and material to be defined in the actual layout where the work occurs. The Standardized Work Chart exists to make this definition explicit.

This chart connects the work sequence to the physical environment. It shows where work is performed, how operators move, and how material flows through the process. By placing the method directly on the layout, Lean TPS ensures that normal and abnormal conditions can be seen immediately at the gemba. While the Standardized Work Combination Table defines time and balance, the Standardized Work Chart translates that information into physical reality, making walking distance, handoffs, and material location visible at a glance.

Figure 6. Standardized Work Chart Showing Sequence and Operator Motion

The Standardized Work Chart defines the work sequence, operator path, and material interaction so deviations from normal are visible and Quality risks are exposed.

Work must be defined in the workplace, not in isolation

The Standardized Work Chart maps each step of the sequence onto the actual work area. Operator movement, pickup points, inspection locations, and handoffs are all shown together. This makes unnecessary motion, backtracking, and unclear handoffs visible. When the actual movement differs from the defined path, the deviation is apparent without discussion. Extended walking paths immediately signal imbalance or poor material placement, allowing motion waste to be addressed through layout and sequencing rather than operator effort.

By linking sequence to layout, the chart exposes problems that are hidden in task lists. Congestion, excessive reaching, poor material placement, and unsafe movement become visible when viewed spatially. These conditions often create Quality problems indirectly by increasing fatigue, distraction, or inconsistency. The chart allows these risks to be addressed through design rather than coaching alone.

Quality checkpoints are intentionally embedded within the sequence. Inspection and verification steps are not separate activities added after the fact. They are placed where they can be performed naturally within the flow of work. Safety devices and lifting mechanisms, typically marked in green, and Quality checkpoints, marked in yellow, are intentionally positioned to make risk, verification, and protection visible rather than assumed. This reinforces the Lean TPS principle that Quality is built into the process rather than inspected in at the end.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, this spatial definition becomes essential. Human and Humanoid operators must share space safely and predictably under the same Standardized Work. Paths, approach angles, handoff locations, and safety zones must be unambiguous. The Standardized Work Chart provides a common visual control that both Human and Humanoid systems can follow, reducing the risk of collision, delay, or Quality loss.

The Standardized Work Chart is not a drawing exercise. It is a confirmation mechanism. It answers whether the defined sequence can be performed safely, repeatedly, and within the designed flow. When the answer is no, the deviation is visible and improvement can begin.

This is why Lean TPS treats the Standardized Work Chart as foundational. It protects Quality by making the work method visible in the place where the work actually happens.

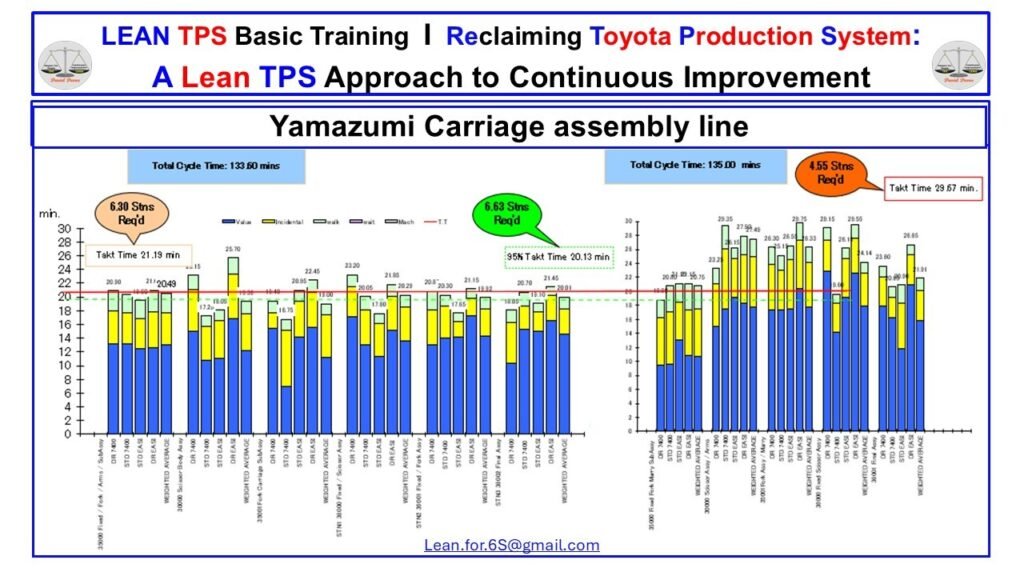

7. Yamazumi Reveals Imbalance in the Workload

Why Lean TPS uses stacked work analysis to protect Quality and stabilize flow

Balanced work is a requirement for stable flow, not an outcome that appears on its own. Lean TPS uses Yamazumi to make workload distribution visible across operators and stations so imbalance can be corrected before it creates instability or Quality loss. When total station time from the SWCT is stacked against takt time, the gap between what is required and what is possible becomes immediately visible.

Yamazumi translates the Standardized Work Combination Table into a visual comparison. While the SWCT defines sequence, manual work, walk time, and machine time, Yamazumi shows how that defined work is distributed across stations at a given takt. This makes it possible to see whether work content is aligned, overloaded, or underutilized without relying on averages or post-fact analysis.

Figure 7. Yamazumi Chart Showing Total Station Time Against Takt

Yamazumi visualizes SWCT station totals by stacking value-added work with walking, waiting, and machine time against takt so redistribution decisions protect Quality and flow.

Uneven work creates instability even when averages appear acceptable

The Yamazumi chart displays each station’s work content using the same vertical scale and takt reference. When a bar exceeds takt, overburden exists. When a bar falls well below takt, unused capacity is present. Both conditions introduce instability. The chart makes these conditions visible at a glance using a common scale, allowing cause and effect to be understood immediately.

In this example, the Yamazumi is intentionally shown with identical scaling on both sides to visualize the impact of takt change. The red line marks the takt reference, while the blue area shows value-added work growing as work is redistributed. Total cycle time remains nearly constant, but the number of stations required changes. This shift is not achieved by altering sequence, but by redistributing work elements already defined in the SWCT.

This is where the SWCT proves its value. Because work is explicitly defined by element and sequence, it can be pulled backward station by station as takt changes. A six-station configuration can be rebalanced to five stations without redefining how the product is assembled. Yamazumi simply exposes that flexibility visually so decisions can be made with confidence.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, this distinction becomes critical. Humans are constrained by ergonomic limits such as lift thresholds, reach, and fatigue. Humanoids operate under different constraints. They are physically uniform and can perform tasks beyond Human ergonomic limits as long as Humanoid safety limits are respected. When trained across all stations of the original SWCT, a Humanoid requires virtually no re-learning when work is redistributed. The sequence does not change. Only the allocation does.

This makes Yamazumi a system-level decision tool rather than a balancing chart. It shows how takt change affects station count, workload distribution, and the mix of Human and Humanoid work without introducing risk to Quality or flow. The flexibility observed in the chart exists only because the SWCT provides a disciplined, modular definition of work.

Yamazumi is not used to optimize individuals. It is used to stabilize the system. By making imbalance visible, it allows leaders to redesign work deliberately as demand changes while protecting sequence, flow, and Quality. This is why Lean TPS treats Yamazumi as a critical visual extension of Standardized Work.

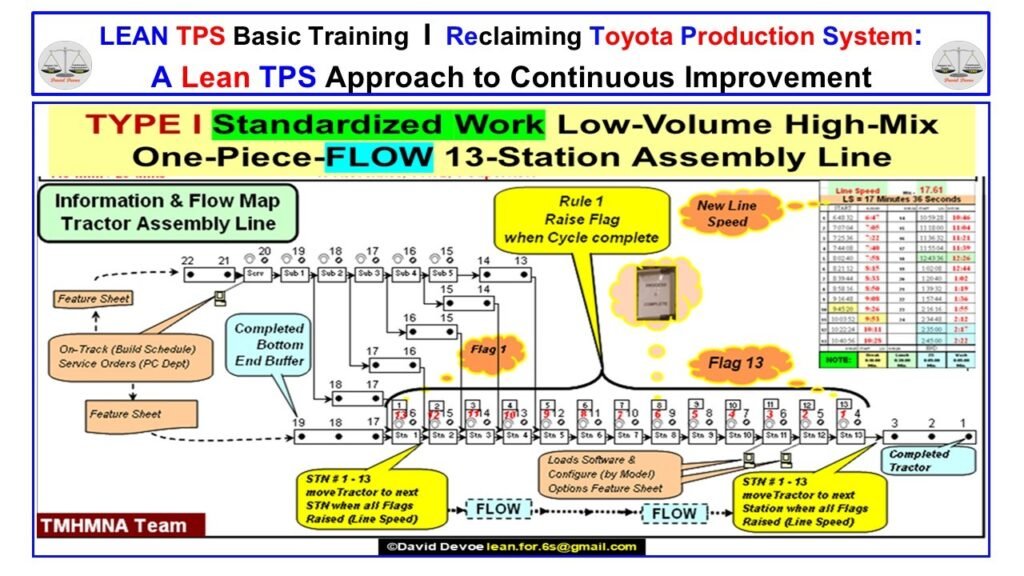

8. Standardized Work Enables One-Piece Flow in High-Mix Environments

Why Lean TPS can sustain flow even when volume is low and mix is high

One-piece flow is often misunderstood as a condition limited to high-volume, repetitive production. Lean TPS proves otherwise. When Standardized Work is clearly defined and rigorously applied, one-piece flow can be sustained even in low-volume, high-mix environments with thousands of product variations.

In high-mix systems, variation itself is not the enemy. Instability is. Lean TPS does not attempt to eliminate mix. It controls how work responds to variation. By defining sequence, timing, movement, and release conditions, Standardized Work prevents variation from turning into disruption, delay, or Quality loss.

This section explains how disciplined Standardized Work, supported by the Standardized Work Combination Table and Yamazumi, enables one-piece flow even when demand, configuration, and work content change continuously.

Figure 8. Standardized Work Supporting One-Piece Flow in a Low-Volume High-Mix Line

Standardized Work defines sequence, timing, and release conditions so one-piece flow can be maintained despite product variation.

Flow is achieved by rules, not by pace alone

In Lean TPS, one-piece flow is governed by operating rules, not informal coordination or individual judgment. Each station follows clearly defined conditions for work completion, handoff, and release. A unit does not advance because an operator feels ready. It advances because the Standardized Work conditions have been met.

In the system shown, physical signals such as flags control movement. These signals replace verbal coordination and assumption. They prevent premature release, downstream waiting, and uncontrolled accumulation of work-in-process. One unit moves forward only when the next station is ready to receive it.

Standardized Work defines when an operator may advance the product and when they must wait. This discipline ensures that one unit flows through the line at a time, even though work content varies significantly by model and option mix. Flow is therefore controlled by method, not by experience or improvisation. This directly protects Quality by preventing rushing, skipped steps, and silent compensation.

Information flow is integrated into the work sequence itself. Feature sheets, configuration data, and build instructions arrive at the point of use in synchronization with the product. Operators do not search for information or rely on memory. Quality requirements change with the product in a controlled and visible manner.

The Standardized Work Combination Table provides the structural flexibility that makes this possible. When takt changes, work can be redistributed across stations without altering the sequence of assembly. Value-added work is pulled backward or pushed forward across stations based on the new takt, while the order of operations remains intact. This allows the line to move, for example, from six stations to five without redesigning the process logic.

Yamazumi visualizes this redistribution. It makes the impact of takt changes immediately visible by showing how work content shifts across stations and how the number of required operators changes. The Yamazumi does not control the system. The Standardized Work Combination Table does. Yamazumi reveals the effect of that control.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, this capability becomes even more important. Humans are typically loaded to approximately ninety-five percent of takt to manage fatigue and sustain performance. Humanoids can operate at one hundred percent of takt without degradation and without requiring breaks. When takt changes, humanoids trained across all stations on the original configuration can transition to the new station balance with minimal retraining.

Ergonomic constraints further influence this redistribution. Tasks such as lifting beyond established human limits may be reassigned to humanoids when appropriate, while stations with specialized fixtures, cranes, or access constraints may limit how much work can be pulled backward. Standardized Work makes these constraints explicit so flow decisions are based on system design rather than assumption.

One-piece flow in high-mix environments is not fragile when built on Standardized Work. It is resilient. Problems surface immediately because work cannot advance unless conditions are met. When an abnormality occurs, flow stops and the issue is addressed before defects propagate.

This is why Lean TPS strengthens standards as complexity increases. Standardized Work enables one-piece flow by defining clear rules for movement, information, and completion. As a result, Quality is protected even as mix increases, takt changes, and Human–Humanoid work is integrated into the system.

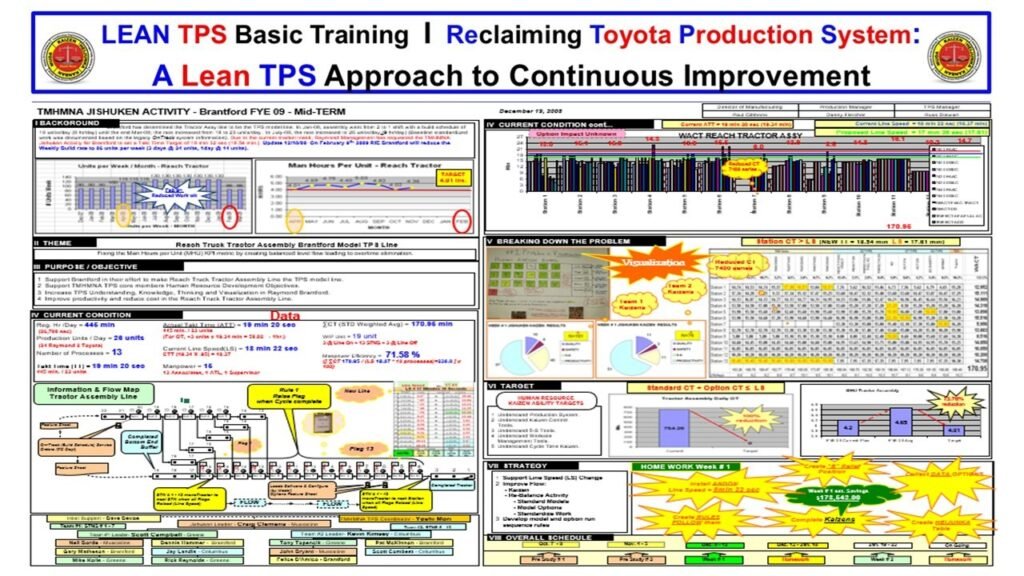

9. Jishuken Uses Standardized Work to Drive System-Level Improvement

Why Lean TPS improves the system, not isolated processes

Lean TPS does not rely on isolated kaizen events to improve performance. It uses Jishuken as a disciplined method to study, understand, and improve the production system as a whole. Standardized Work provides the factual baseline that allows this study to occur without assumption, opinion, or local optimization. This section explains how Jishuken depends on Standardized Work to identify root causes and deliver sustained Quality improvement.

Jishuken begins with a deep understanding of the current condition. That understanding is only possible when work is clearly defined and performed consistently. Without Standardized Work, variation overwhelms analysis, obscures cause and effect, and prevents teams from distinguishing system problems from individual behavior.

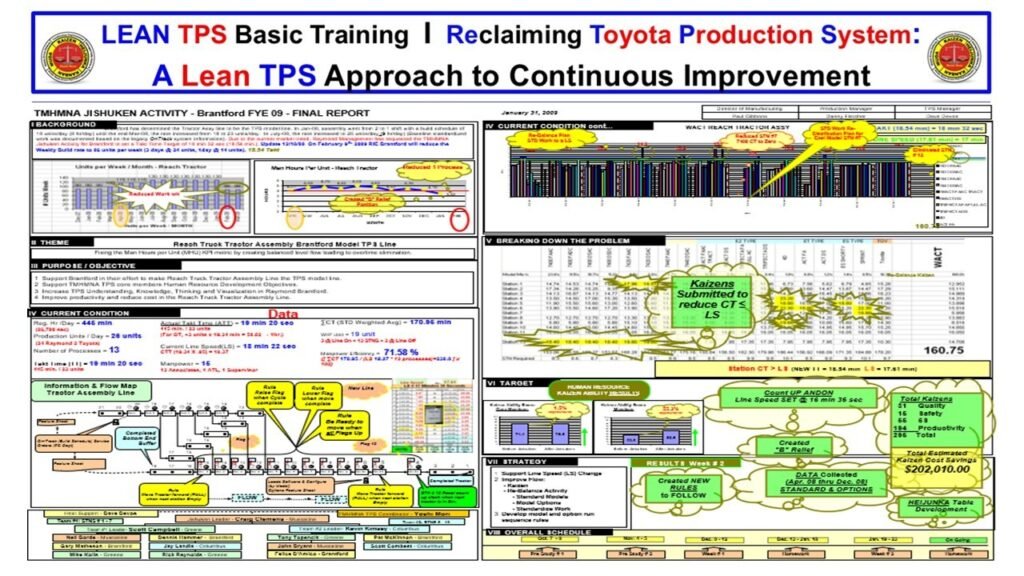

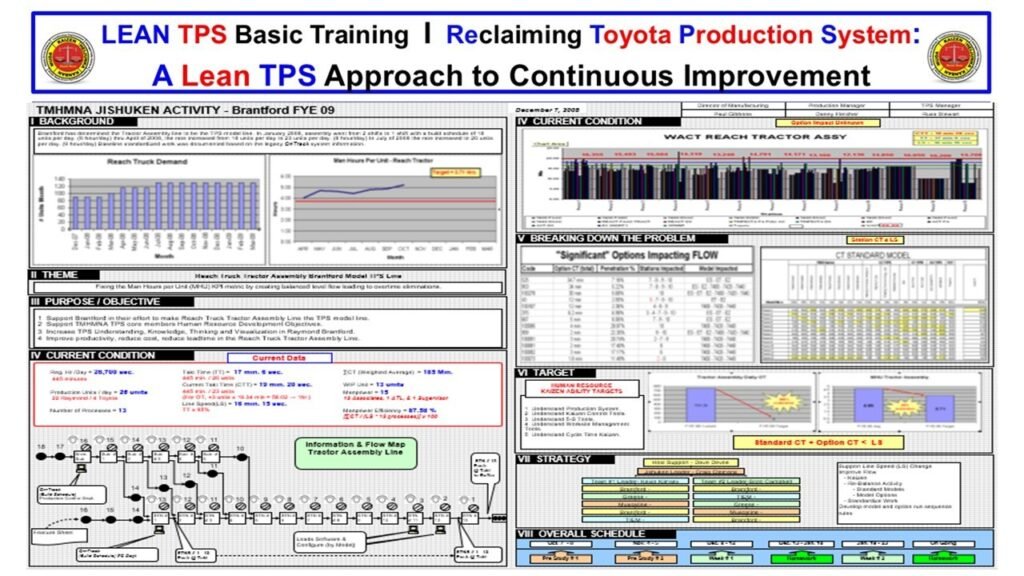

Figure 9. Jishuken Activity Driven by Standardized Work and Data

Standardized Work enables Jishuken teams to visualize the system, establish factual baselines, and drive improvement through PDCA.

System improvement requires a stable and visible baseline

The A3 shown here represents the primary working document used during a Jishuken. It is not a report. It is a visual control that captures the entire improvement story on one sheet of paper. Background, theme, purpose, current conditions, problem breakdown, targets, strategy, and schedule are all presented together. This format forces clarity, discipline, and alignment.

Standardized Work makes this possible. Because work is defined and repeatable, the current condition can be expressed using numbers, charts, and visual comparisons rather than narrative explanation. Cycle times, workload distribution, flow paths, and Quality results are anchored to a known standard. This allows Jishuken teams to analyze the system objectively and prevents discussion from drifting into opinion or anecdote.

The A3 structure follows PDCA. It establishes the baseline in the Plan phase, exposes gaps and causes during Do and Check, and confirms countermeasures before new standards are set in Act. Each section of the A3 exists to answer a specific question about the system, not to describe activity. This discipline ensures that improvement is driven by facts and verified through observation.

At TMHMNA, Jishuken A3s were developed in three stages: kickoff, mid-term, and final. Each A3 captured the evolving understanding of the system as changes were tested and verified. The final A3 shown here consolidates that learning and becomes the reference for yokoten across lines, products, and business units. It is both a record of improvement and a teaching tool.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, this process becomes even more critical. Interactions between human work, machine cycles, and automated decision logic must be evaluated at the system level. Standardized Work provides the stable reference that allows Jishuken teams to redesign flow, balance work, and protect Quality without increasing risk.

Jishuken is not a problem-solving shortcut. It is a structured learning process grounded in facts. Standardized Work ensures those facts are reliable. Together, they enable deliberate, repeatable system improvement and form the foundation for sustained Quality.

10. Standardized Work Exposes Variation Across Models and Stations

Why Lean TPS makes variation visible instead of averaging it away

Variation is one of the greatest threats to Quality in mixed-model production. When multiple base models are built on the same line, differences in work content, sequence, and timing accumulate quickly. Lean TPS does not attempt to eliminate this variation through averaging. Instead, it uses Standardized Work to make variation visible at each station so it can be understood and addressed deliberately.

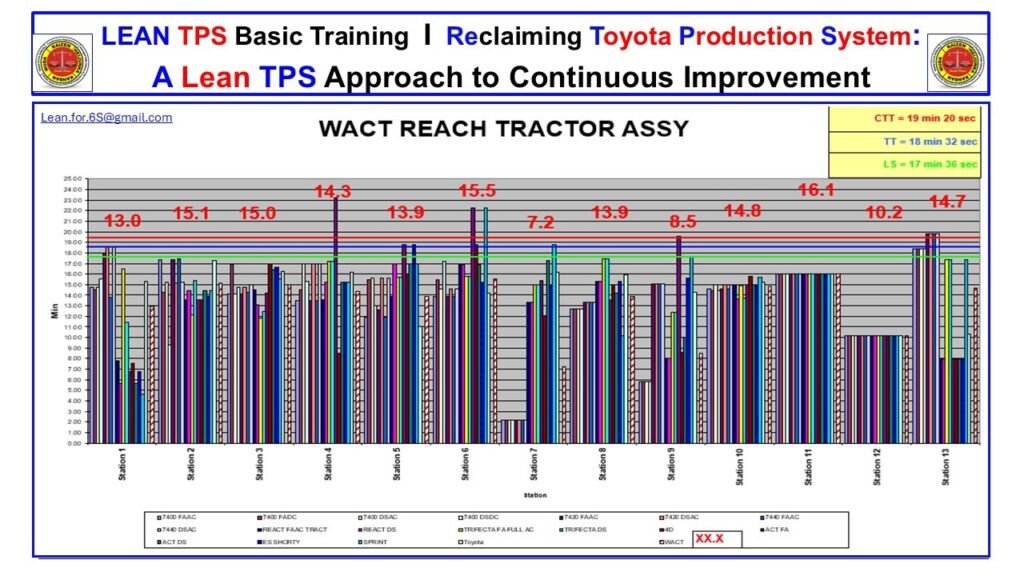

This section focuses on how Lean TPS uses Weighted Average Cycle Time (WACT) as a visual starting point to expose variation across stations and base models. Rather than hiding instability behind averages, this approach shows where variation originates, where flow is threatened, and where Quality risk increases when variation is left unmanaged.

Figure 10. Cycle Time Variation Across Stations and Models

Weighted Average Cycle Time (WACT) visualizes cycle time differences by station across base models, making variation visible so imbalance, sequencing risk, and Quality exposure can be addressed deliberately.

Averages hide instability and delay Quality response

When performance is viewed only through overall averages, significant instability is concealed. A station may appear to meet takt on average while repeatedly exceeding it for specific base models. These exceedances create overburden, waiting, and rushed work, all of which increase Quality risk. Lean TPS uses WACT to prevent this masking effect by making base-model variation visible station by station.

This chart is not a stacked work-element diagram and it does not represent option mix. It shows the weighted average cycle time of each base model at each station. Its purpose is speed and clarity. A large team can stand at the gemba, one person per station, observe a single build cycle, and capture real data quickly. This allows Standardized Work to be grounded in reality rather than assumption.

WACT is especially powerful at the kickoff of an A3 or Jishuken activity. By visualizing where base models differ most by station, it directs attention to where deeper Standardized Work definition, SWCT refinement, or kaizen is required. It tells leaders where to look first.

If this were true one-piece flow with one unit per station, each complete pass through the line would represent a single “stroke.” For example, a 13-station line with 24 units produced would generate 24 strokes. This chart does not show strokes. Instead, it provides a weighted view that highlights where those strokes would break down due to variation if left unaddressed.

This visibility also supports sequencing. By understanding which base models carry longer or shorter cycle times at specific stations, production can be sequenced so longer cycles are absorbed by shorter cycles before or after. This sequencing protects flow and supports heijunka without forcing local compensation or hidden recovery.

Standardized Work prevents operators from compensating locally to hide this variation. Without a defined standard, people work faster on some units to recover time lost on others. This behavior masks instability while increasing fatigue and error risk. A visible standard removes the incentive to compensate and forces the system to confront imbalance directly.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, unmanaged variation is even more dangerous. Humans adapt naturally while machine and humanoid cycles are fixed. If variation is not exposed at the system level, interactions become unpredictable. Standardized Work, supported by WACT visibility, provides the reference needed to synchronize humans and humanoids safely.

Variation itself is not the enemy. Uncontrolled variation is. Lean TPS uses Standardized Work and WACT to separate normal variation from abnormal conditions that threaten flow and Quality. Once visible, variation can be addressed through redesign, rebalance, or sequencing rather than absorbed through human effort.

This is why Lean TPS insists on exposing variation rather than averaging it away. Visibility comes first. Stability and Quality follow.

11. Operator Activity Charts Reveal How Work Is Actually Performed

Why Lean TPS analyzes motion and time together to protect Quality

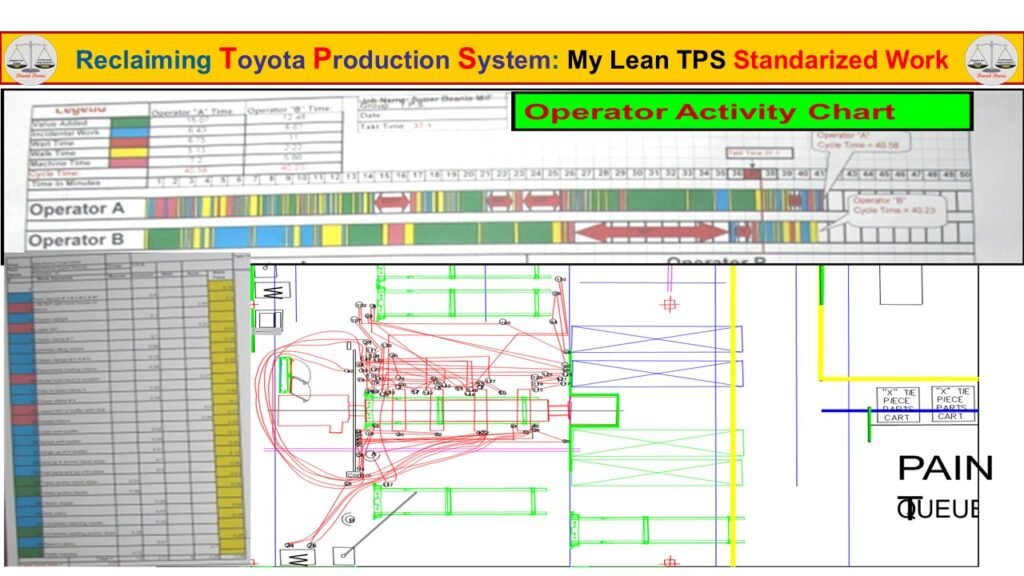

Standardized Work must reflect reality at the gemba, not how work is assumed to be performed. Lean TPS uses Operator Activity Charts to capture how operators actually spend their time during a cycle. By breaking work into value added, walking, waiting, and machine interaction, the chart exposes hidden inefficiencies that directly affect Quality and stability.

This analysis goes beyond task lists. It shows how motion, delays, and interruptions accumulate across a cycle and where instability is introduced through poor layout, unclear sequence, or unbalanced work design.

Figure 11. Operator Activity Chart Showing Time and Motion by Operator

Operator Activity Charts make walking, waiting, and uneven work visible so motion related Quality risks can be eliminated.

Hidden motion and waiting reveal system design failure, not operator performance

Operator Activity Charts display work content over time for each operator, allowing value added work to be distinguished clearly from walking, waiting, and incidental motion. In this example, two operators performed the same welding process, yet the chart revealed extensive walk and wait time that was not visible through observation alone.

A key limitation of the initial condition was that individual walking paths were difficult to distinguish by operator. However, when combined with the Standardized Work Combination Table, the scale revealed excessive non-value-added time for both operators. This made the underlying system problem visible rather than attributing delays to individual behavior.

The value added welding work did not change and could not change. All improvement opportunity existed in walking, waiting, and incidental motion. By visualizing where this time occurred, the team was able to redesign the work and reduce the cell from two operators to one. Walking occurrences were reduced dramatically, from approximately sixteen to three per cycle, while maintaining the same Quality output.

Operator participation transforms charts into learning tools

The welders working in this cell actively participated in the analysis and rebalance. Because the chart showed exactly where time was being lost, operators understood both the reason for change and the specific locations where improvement was required. This converted the exercise from enforcement into learning.

Lean TPS uses Operator Activity Charts to teach people how systems behave. When operators see their own motion and waiting reflected objectively, improvement becomes logical rather than emotional. This builds capability and reinforces standardized thinking across the organization.

Eliminating the welding “black art” through system design

This cell was not improved by asking operators to work faster or differently. Instead, the redesign focused on eliminating the individual “black art” historically associated with welding large frames. A dedicated positioning fixture was developed to clamp and pre-distort the rails into a controlled geometry prior to welding.

By embedding knowledge into the fixture, variation between individual welders was removed. The fixture was designed to accommodate fourteen base models and future product designs, replacing manual clamping, spreading, and adjustment techniques that varied by individual. This made the process inherently repeatable and suitable for Standardized Work.

Why this chart is foundational for Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid environments, Operator Activity Charts become even more critical. Humans adapt naturally to variation, while humanoid systems operate within defined motion and timing constraints. Without understanding and stabilizing human motion, interaction points become unpredictable.

When used together with the Standardized Work Chart, Operator Activity Charts allow exact visualization of what the human is doing and what the humanoid is doing in real time. Side-by-side activity timelines combined with floor layout overlays provide precise training data for humanoids and validate safe, repeatable interaction points.

This cell also illustrates why humanoids can outperform traditional welding robot systems in certain applications. The cell contained two machines: a positioning fixture and a weld robot arm. Operators performed tack welding and completed welds the robot could not reliably access. A humanoid, with greater degrees of freedom and no need for fencing or fixed robot paths, could replace much of this automation while reducing infrastructure, floor space, and capital cost.

Why Lean TPS insists on motion visibility

Operator Activity Charts are not created to measure individual performance. They are created to expose system design problems. Excess walking indicates poor layout. Waiting reveals imbalance between people, machines, or sequence. Once visible, these conditions can be eliminated without increasing burden.

Together with Standardized Work Charts and Combination Tables, Operator Activity Charts ensure that time, motion, and sequence are aligned. When this alignment exists, work becomes stable, repeatable, and capable of sustaining Quality. This is why Lean TPS treats motion visibility as a prerequisite for both improvement and future Human–Humanoid system design.

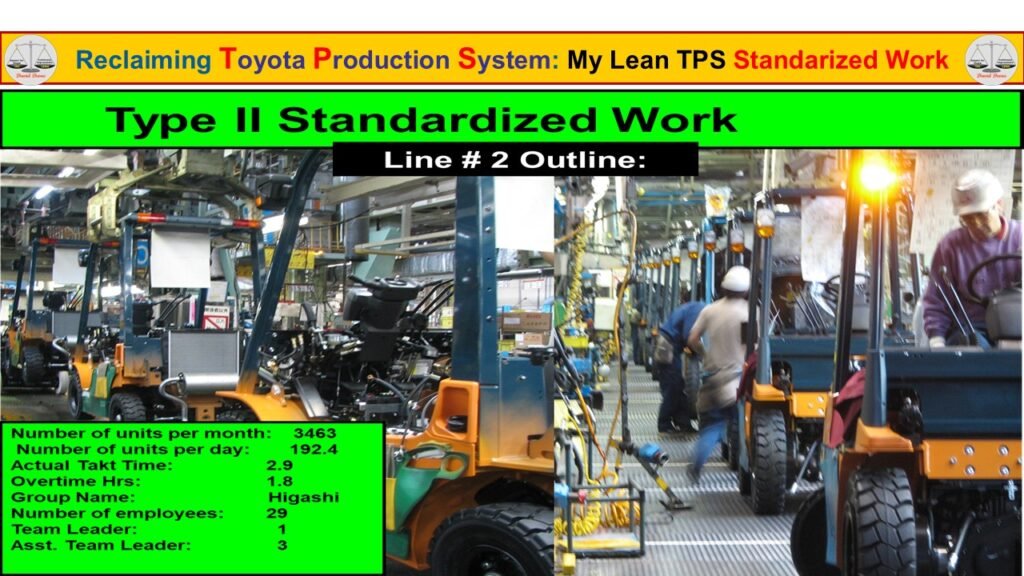

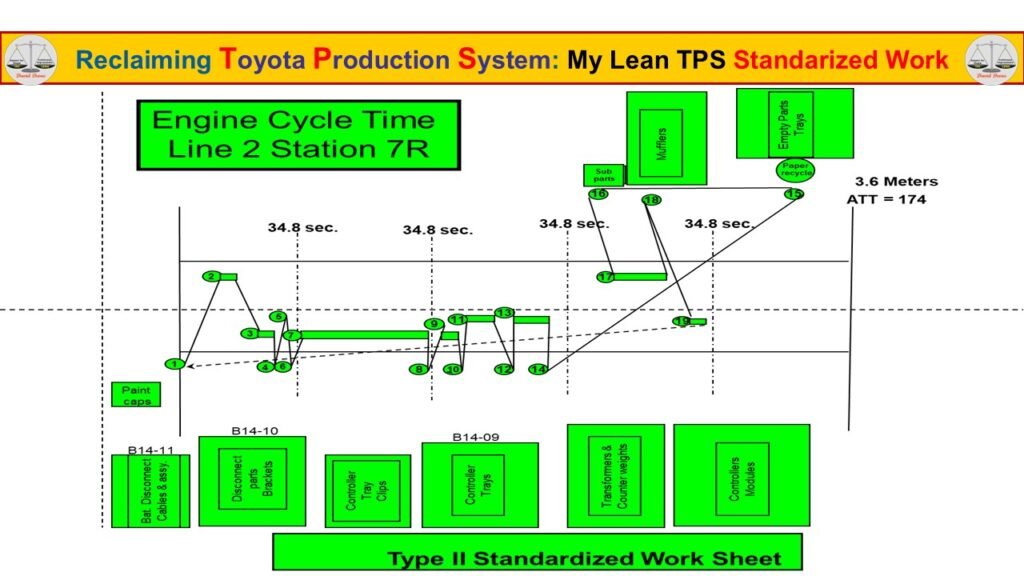

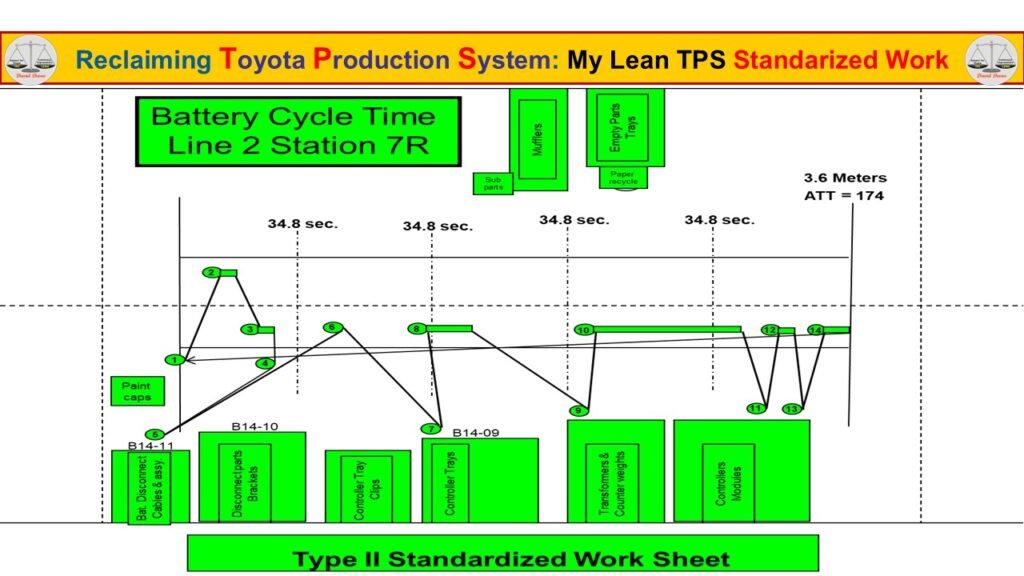

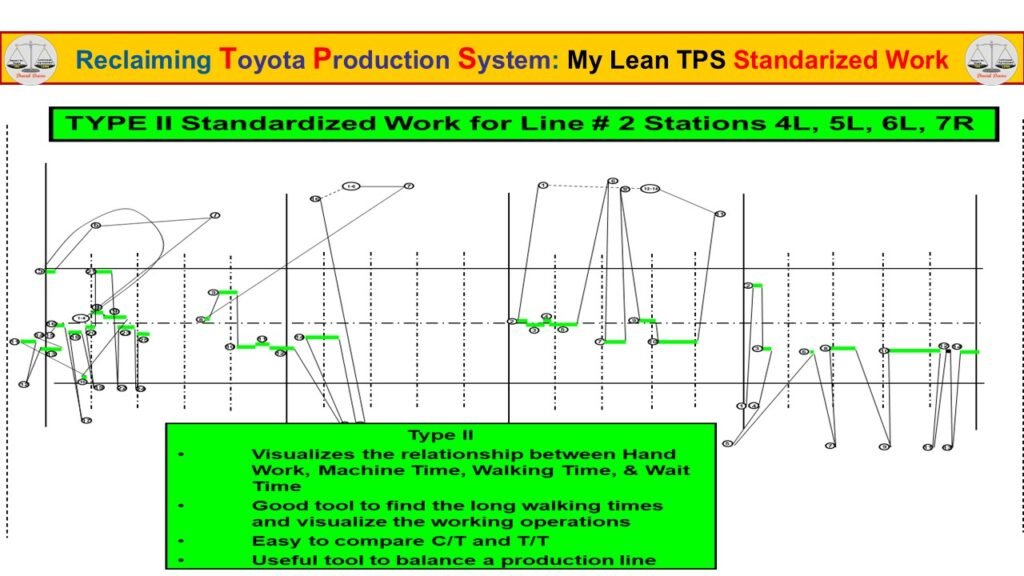

12. Type II Standardized Work Stabilizes Complex Flow Lines

Why Lean TPS applies different Standardized Work logic when flow spans multiple stations

Not all production systems can operate as tightly coupled one-piece flow. When an assembly line is long, highly interconnected, or constrained by shared resources, Lean TPS applies Type II Standardized Work. This form of Standardized Work is designed to stabilize flow at the line level, not at a single station. It provides structure where complexity would otherwise create chronic instability and increasing Quality risk.

Type II Standardized Work recognizes that synchronization across many stations requires clearly defined operating rules, release conditions, and disciplined coordination. Without this structure, variation accumulates across the line and problems propagate downstream before they can be detected or contained.

Figure 12. Type II Standardized Work Applied to a Multi-Station Assembly Line

Type II Standardized Work defines line level conditions, roles, and release rules to stabilize flow and protect Quality across complex assembly systems.

Line stability depends on shared rules, not local optimization

In Type II Standardized Work, the focus shifts from optimizing individual stations to managing the performance of the line as a system. Takt time, staffing levels, pitch, and release conditions are defined at the line level. Operators and team leaders work to a shared rhythm rather than compensating locally. This prevents one area from improving output while creating instability elsewhere.

Clear roles and responsibilities are explicitly built into the Standardized Work. Team leaders, support functions, and relief roles are defined as part of the system, not as exceptions. Abnormalities are addressed quickly without disrupting flow. Overtime, staffing adjustments, and recovery actions are treated as system variables rather than ad hoc responses. This discipline protects Quality by preventing uncontrolled reactions to daily variation.

Information flow is also standardized. Build schedules, option content, sequencing rules, and line speed changes are communicated visually so all stations respond consistently. When changes occur, they occur deliberately and visibly. This prevents confusion, rework, and missed Quality checks that often accompany informal coordination in complex lines.

This assembly line example illustrates a low-volume, high-mix mixed-model system that is not automotive. Different product types, including battery-powered units and internal combustion units, are built on the same moving line. Flow is stabilized not by averaging cycle times, but by deliberate sequencing rules. Yamazumi is used to visualize and confirm that stability can only be achieved by sending one battery unit followed by a defined number of internal combustion units. The rule exists because of cycle time differences and shared constraints, not because of preference.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, Type II Standardized Work becomes even more important. As human work and humanoid work interact across longer lines, coordination must be precise. Release rules, response timing, and recovery actions must be unambiguous to both humans and humanoids. Humanoids introduce new capabilities. They can absorb variation in cycle time, pitch, and station length more easily than traditional automation. However, without Type II Standardized Work, those capabilities would increase risk rather than reduce it.

Type II Standardized Work does not reduce flexibility. It creates controlled flexibility. By defining how the system responds to change, Lean TPS allows variation to be absorbed without destabilizing flow or compromising Quality. In a future MMHH environment, some traditional sequencing constraints may be reduced, but system-level rules will remain essential.

This is why Lean TPS distinguishes between Type I and Type II Standardized Work. Each serves a different purpose, but both exist for the same reason: to protect Quality by creating stability where complexity would otherwise dominate.

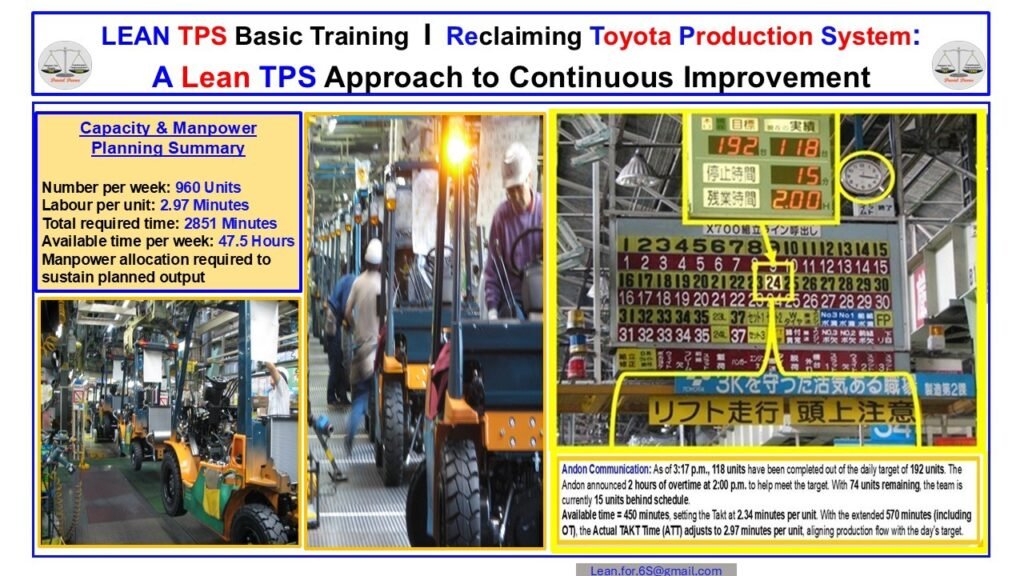

13. Takt Time Sets the Pace for Quality and Stability

Why Lean TPS treats takt time as a system constraint, not a target

Takt time defines the pace at which work must be completed to meet customer demand. In Lean TPS, takt time is not a productivity goal and not a pressure mechanism. It is a system constraint that aligns all work to demand so Quality can be protected and instability can be exposed.

This section clarifies why takt time is calculated deliberately and why changes in demand must translate directly into changes in the pace of work. When takt time is misunderstood or ignored, work becomes self paced, variation increases, and Quality risk grows.

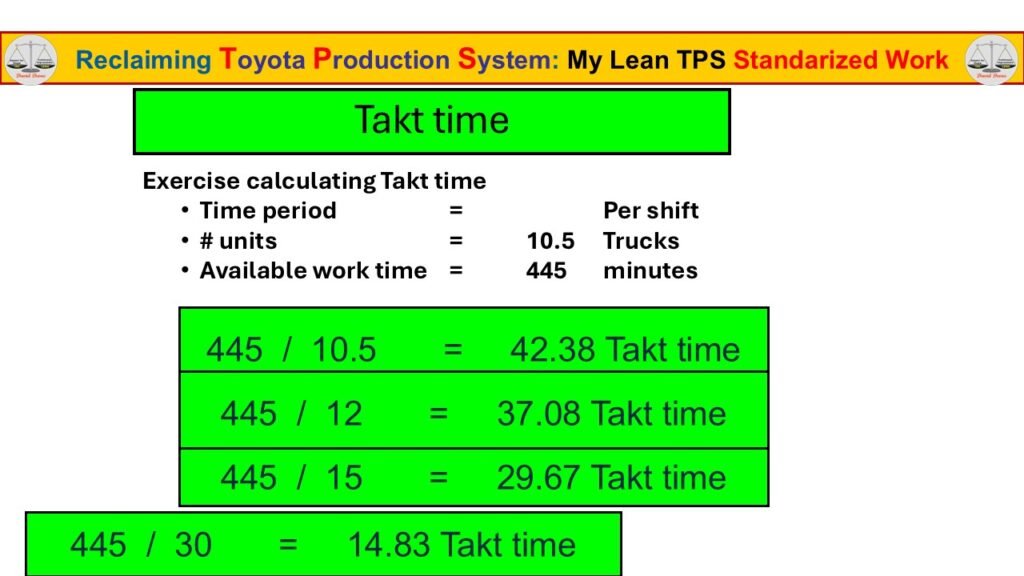

Figure 13. Calculating Takt Time Based on Available Work Time and Demand

Takt time is calculated by dividing available work time by required output, establishing the pace required to meet demand without overburden.

Takt time defines normal operating conditions

Takt time establishes what normal looks like for the system. By dividing available work time by the number of units required, Lean TPS creates a clear reference for how often a unit must be completed. This reference allows leaders and operators to judge whether work is being performed too fast, too slow, or unevenly.

As demand changes, takt time changes. Producing fewer units increases takt time. Producing more units decreases it. This relationship forces the system to respond to demand through design rather than effort. Staffing, work content, and line configuration are adjusted to match takt instead of asking operators to compensate.

Without a defined takt time, work defaults to individual judgment. Operators speed up to recover lost time or slow down when pressure eases. These adjustments hide instability and increase the likelihood of missed steps, skipped checks, and Quality defects. Takt time removes this ambiguity by defining a single pace for the entire system.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, takt time becomes a shared constraint for both humans and machines. Human work adapts naturally, while automated cycles are fixed. Takt time provides the reference that allows both to be synchronized deliberately. When takt is respected, interaction points are predictable and Quality risk is reduced.

Takt time does not guarantee stability on its own. It must be supported by balanced work, defined sequence, and controlled work-in-process. However, without takt time, these elements cannot be aligned. Takt time anchors Standardized Work to demand and ensures that improvement efforts focus on system design rather than short term output.

This is why Lean TPS begins Standardized Work with takt time. It defines the rhythm of work, exposes mismatch between demand and capacity, and creates the conditions required to protect Quality as conditions change.

14. Takt Time Scales Through the System

Why Lean TPS uses takt time to synchronize subassemblies to final assembly

Takt time applies at every level of the system, not only at final assembly. In Lean TPS, takt time is the single demand signal that governs how all processes are designed, connected, and synchronized. When applied correctly, takt time allows complex systems to operate with stability rather than collapsing under variation.

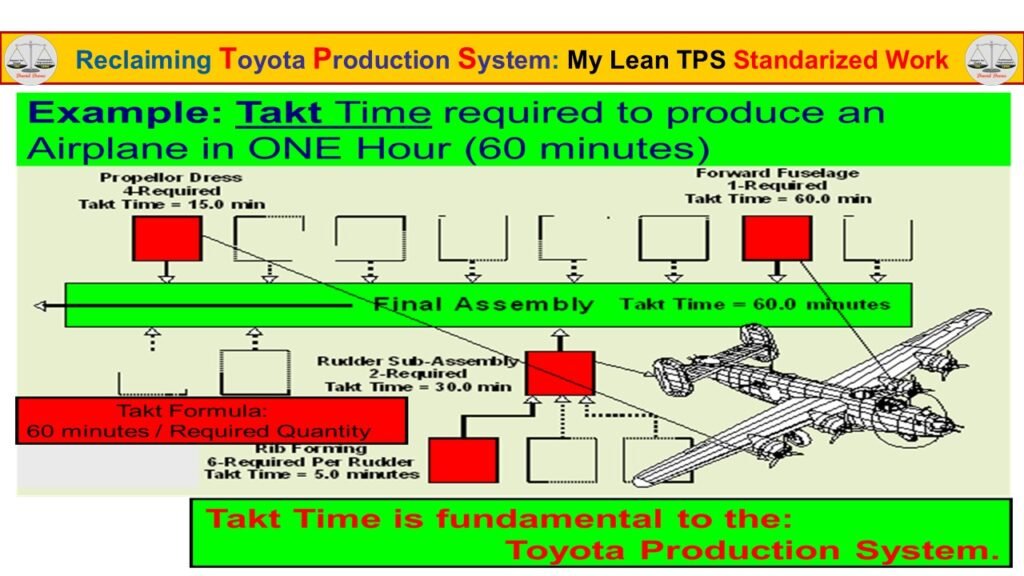

This section explains how takt time scales through subassemblies by arithmetic, not negotiation. The example shown demonstrates how one demand signal is translated into multiple synchronized processes without averaging, buffering, or local optimization.

Figure 14. Example of Takt Time Required to Produce One Airplane Per Hour

Takt time scales from final assembly to subassemblies by dividing required quantity into the available time while maintaining system synchronization.

Takt time governs system design, not individual operations

In this example, the demand is one airplane per hour. Final assembly therefore operates at a takt time of 60 minutes. This does not imply that every operation takes 60 minutes. It means the system must deliver one completed airplane every 60 minutes, consistently, without interruption.

Subassemblies are designed by working backward from this requirement. If four propeller assemblies are required per airplane, the propeller process must operate at a 15 minute takt. If two rudder subassemblies are required, they must operate at a 30 minute takt. If twelve rib formings are required, they must operate at a 5 minute takt. Each process is synchronized to final demand through calculation, not compromise.

This is a core Lean TPS principle. Takt time is not averaged across departments and it is not adjusted to suit local convenience. It is calculated once from demand and available time, then used to design the entire system. Staffing, work division, and sequencing are adjusted to takt, not the other way around.

When this logic is ignored, subassemblies overproduce or underproduce relative to final assembly. Inventory accumulates, queues form, and final assembly is forced to absorb instability. Quality deteriorates because work is no longer performed under repeatable, predictable conditions.

Takt time as the starting point for system architecture

This example reflects a historical reality. The concept of one unit per hour was not a production target. It was the starting constraint used to design the entire assembly system. Facility layout, material flow, tooling, staffing, and training were all derived from that single takt requirement.

Training methods such as TWI were essential because the system depended on repeatability, interchangeability, and consistency rather than individual skill. Standardized Work made it possible to train large numbers of new workers quickly while maintaining Quality. Universal parts, repeatable processes, and disciplined work methods were not optional. They were required to sustain takt.

This logic directly applies to future production systems. In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, takt time remains the governing constraint. Humanoids do not eliminate takt. They make it easier to adhere to it. Their ability to execute defined sequences, remember Standardized Work Combination Tables, and adapt work content precisely provides new flexibility without breaking system synchronization.

Subassemblies with fixed automated cycles and stations with variable human work can coexist only when takt time is used as the common reference. Without it, complexity overwhelms coordination. With it, variation is absorbed through design rather than effort.

Takt time enables complexity without chaos

The airplane example demonstrates that takt time does not limit flexibility. It enables it. By anchoring every process to the same demand signal, Lean TPS allows complex products, multiple subassemblies, and variable work content to flow together as one system.

This is why takt time is fundamental to the Toyota Production System. It translates customer demand into a system-wide rhythm that governs design, exposes imbalance, and prevents local decisions from damaging overall Quality.

15. Type II Standardized Work: Baton Touch Logistics and Kanban

Why Lean TPS standardizes logistics work to protect flow and Quality in mixed and variable environments

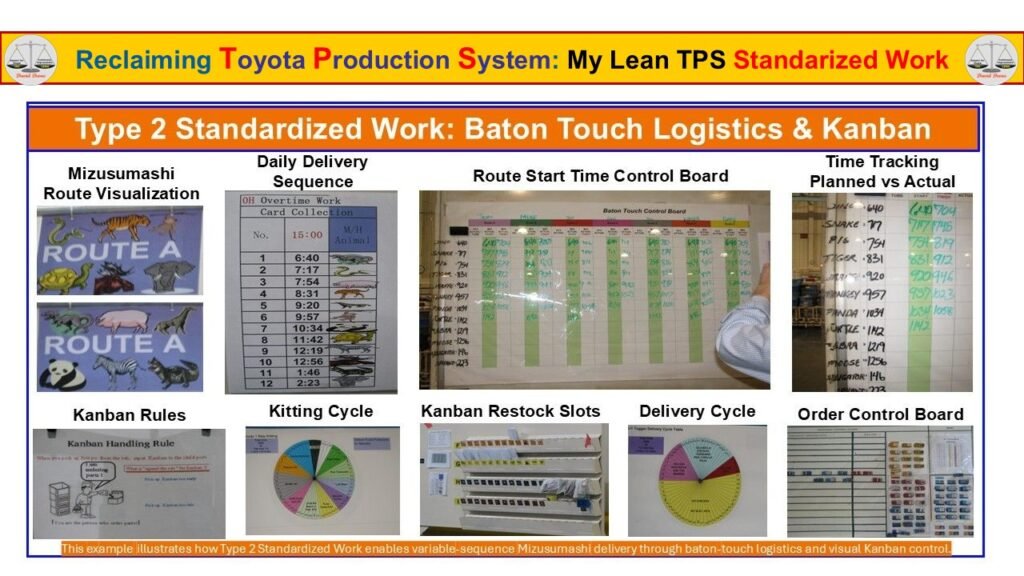

Type II Standardized Work addresses work that does not follow a fixed, repetitive production sequence but must still operate with discipline and precision. Logistics, material handling, and mizusumashi activity fall into this category. This section explains how Lean TPS applies Standardized Work to variable delivery routes through baton touch logistics and visual Kanban control so that flow and Quality are protected even when sequence changes.

Figure 15. Type II Standardized Work Using Baton Touch Logistics and Kanban

Type II Standardized Work defines routes, timing, handoffs, and control points so variable-sequence logistics can operate predictably without disrupting production flow.

Standardizing logistics without freezing sequence

In Lean TPS, logistics work is never left to individual judgment. Even when delivery routes vary by time, model, or demand, the work is standardized around conditions rather than fixed motion. Baton touch logistics defines exactly where responsibility starts, where it ends, and how work is handed off between cycles. This creates accountability without rigidity.

Mizusumashi routes are visualized so delivery paths are unambiguous. Route start times are controlled through visual boards to prevent early or late delivery. Planned versus actual tracking exposes deviation immediately, before shortages or overstock appear at the line. These controls ensure variation is managed deliberately rather than absorbed by operators.

Kanban rules govern pull, not push. Kitting cycles define when preparation occurs. Restock slots define where material belongs and how much is permitted. Delivery cycles define cadence rather than speed. Order control boards make demand visible and prevent local prioritization from disrupting system flow.

This structure is critical because logistics instability directly creates Quality risk. Late delivery causes line disruption and rushed work. Early delivery creates excess inventory and hides problems. Unclear handoffs create gaps in responsibility. Type II Standardized Work prevents these failures by making logistics work visible, repeatable, and auditable.

System-level JIT enabled by Toyota Tsusho

In advanced TPS systems such as TIEM, logistics Standardized Work extends beyond the plant boundary. Toyota Tsusho operates warehouse-based Just-In-Time inventory systems that regulate material flow between global suppliers and the production line. One-way Kanban is used for overseas supply, with parts released based strictly on line consumption rather than forecast.

At TIEM, material arriving from Japan is often delivered directly from trailers to the line or near-line locations with minimal dwell time. The warehouse functions as a flow regulator, not a buffer. This level of control allows international supply to operate as part of the same TPS system governing production. Jishuken was the method used to teach this system discipline and ensure it was sustained.

This capability demonstrates that Type II Standardized Work is not local optimization. It is system-level synchronization that protects flow and Quality across oceans, facilities, and time zones.

Implications for Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, Type II Standardized Work becomes even more important. Automated systems require precise material availability. Humans naturally compensate when logistics fail. Baton touch logistics prevents humans from becoming buffers for system weakness.

Humanoids introduce a further advantage. While humans rely on visual cues, humanoids can receive real-time signal updates directly. Layout changes, route changes, and condition changes can be transmitted instantly and consistently. Humanoids can also serve as communicators to humans, reinforcing system discipline rather than replacing it.

Type II Standardized Work does not reduce flexibility. It defines the boundaries within which flexibility can exist safely. By standardizing routes, timing, handoffs, and control points, Lean TPS allows logistics to adapt to demand while maintaining flow, stability, and Quality across the entire system.

16. In-Process Stock as a Controlled Condition

Why Lean TPS defines work-in-process as a deliberate control point rather than excess inventory

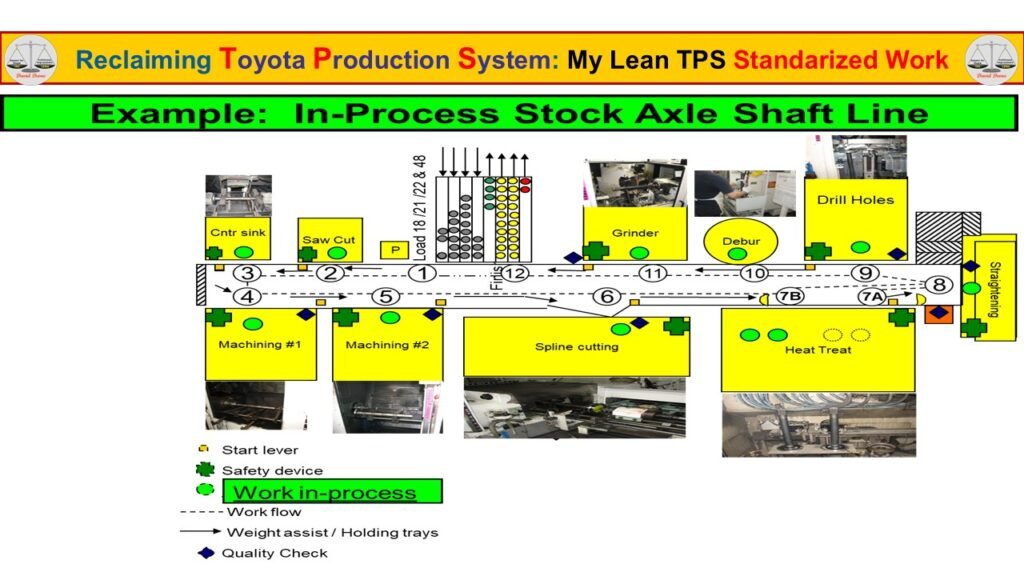

In-Process Stock is one of the three basic elements of Standardized Work because it defines the minimum material required to maintain continuous flow between processes. In Lean TPS, work-in-process is not an outcome of imbalance. It is a designed condition that stabilizes flow, protects Quality, and exposes abnormality immediately. This section uses the axle shaft line to show how intentionally defined work-in-process supports system stability rather than hiding problems.

In-Process Stock exists to separate processes without disconnecting them. Each buffer is positioned, sized, and oriented based on process capability, machine cycle time, transfer method, and Quality risk. When designed correctly, it absorbs minor variation while preserving visibility of larger system issues. When allowed to grow unchecked, it delays feedback, increases handling, and masks instability.

Figure 16. In-Process Stock Control on an Axle Shaft Line

Work-in-process is intentionally positioned and limited between operations to maintain flow, expose abnormalities, and prevent overproduction.

Using work-in-process to stabilize flow

On the axle shaft line, work-in-process is deliberately placed between machining, spline cutting, heat treat, grinding, deburring, drilling, and straightening. Each location has a defined purpose. It allows upstream and downstream processes to operate without interruption while preventing uncontrolled accumulation. The number of pieces, their physical position, and their orientation are all specified as part of Standardized Work.

The visual nature of this design makes normal and abnormal conditions immediately obvious. When work-in-process exceeds its defined quantity or spills outside its intended location, instability is present. When work-in-process is missing, flow interruption is visible without discussion or explanation. Operators and leaders are not required to interpret data. The condition is self-evident at the gemba.

Work-in-process also protects Quality by controlling exposure time, handling, and sequence. Parts are held in defined trays or fixtures that preserve orientation and prevent damage. Quality check points are integrated directly into the flow so defects are identified before they move downstream. Safety devices and start levers are positioned to ensure each operation begins under repeatable conditions.

Critically, work-in-process is tied to takt time and sequence. It exists to absorb small, expected variation while forcing larger problems to surface. When variation exceeds the designed buffer, the system stops hiding the issue and demands investigation. Inventory is not allowed to compensate for poor flow.

In mixed-model and automated environments, uncontrolled work-in-process becomes a major source of risk. Excess inventory increases handling, delays feedback, and creates ambiguity for both humans and machines. Lean TPS prevents this by treating work-in-process as an explicit element of Standardized Work rather than a byproduct of poor design.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, clearly defined work-in-process conditions are essential. Machines require predictable availability. Humans rely on visual control. Humanoids require both structure and clarity. A self-contained, fully defined work-in-process system provides a common reference that allows all three to operate together safely and consistently.

Work-in-process does not exist to protect output. It exists to protect flow and Quality. When correctly designed and maintained, it stabilizes the system. When ignored or allowed to grow, it signals that the system is no longer operating as designed.

17. Auditing Standardized Work to Protect Quality

Why Lean TPS treats audits as verification of the current condition rather than compliance checks

Standardized Work only protects Quality when it is practiced as written and kept current. This section explains how Lean TPS uses a standardized audit to verify that the defined conditions for stable work still exist at the gemba and that improvement has not drifted into variation.

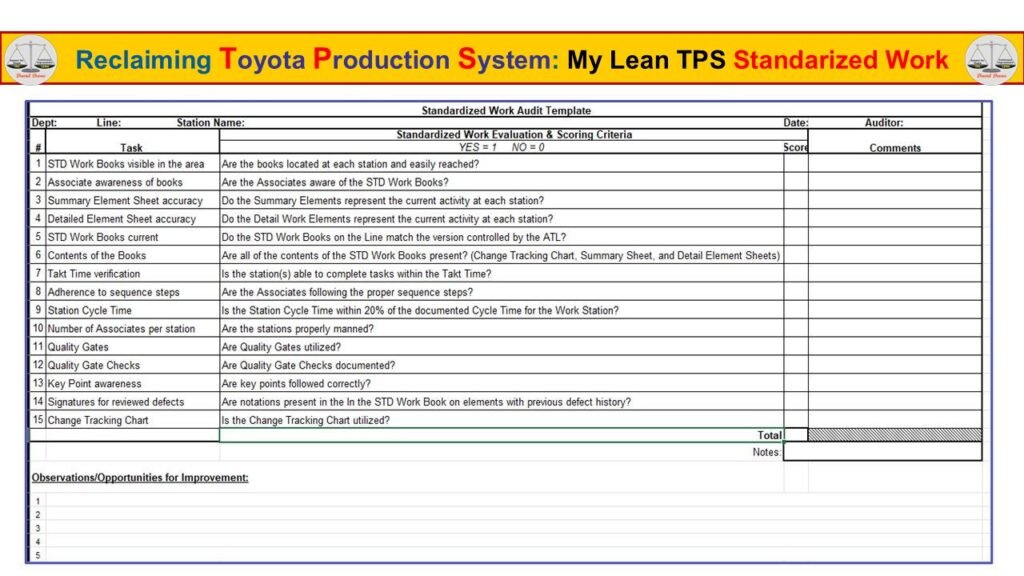

Figure 17. Standardized Work Audit Template

A structured audit verifies that takt, sequence, staffing, Quality checks, and documentation reflect the actual current condition at each station.

Using audits to verify reality, not paperwork

In Lean TPS, an audit is not an inspection of documents. It is a confirmation that the documented standard matches what is happening at the workstation. The audit begins by checking visibility and accessibility. Standardized Work books must be present, current, and understood by associates. If the standard is not visible or not known, it cannot control the work.

The audit then verifies accuracy. Summary sheets and detailed element sheets must reflect the actual work content, sequence, and timing observed at the station. When documents lag behind reality, variation is introduced silently and Quality risk increases. Version control is therefore a Quality control mechanism, not an administrative task.

Takt adherence and cycle time are checked against the defined standard. The purpose is not to judge performance, but to confirm whether the system is capable under normal conditions. When stations consistently exceed takt or operate outside the defined range, the problem belongs to the process design, not the operator.

Sequence adherence and staffing levels are verified next. Lean TPS assumes that correct results come from correct methods performed in the correct order with the correct number of people. Deviations here are early indicators of instability, overload, or missing support.

Quality gates and key points are explicitly audited. Their presence, use, and documentation confirm that defects are being detected where they are designed to be detected. Signatures and notations link current work to known defect history and ensure that past learning is actively applied.

Change tracking closes the loop. Any modification to the work must be recorded, reviewed, and either confirmed as an improvement or rejected. This prevents informal changes from becoming permanent variation.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, audits become even more critical. Humans and machines both rely on the same standard to coordinate safely. When standards drift, machines continue to execute while humans adapt, creating misalignment and risk. The audit restores a shared reference point.

Auditing Standardized Work does not slow improvement. It protects it. By verifying the current condition at the gemba, Lean TPS ensures that Quality, safety, and learning are preserved as the system evolves.

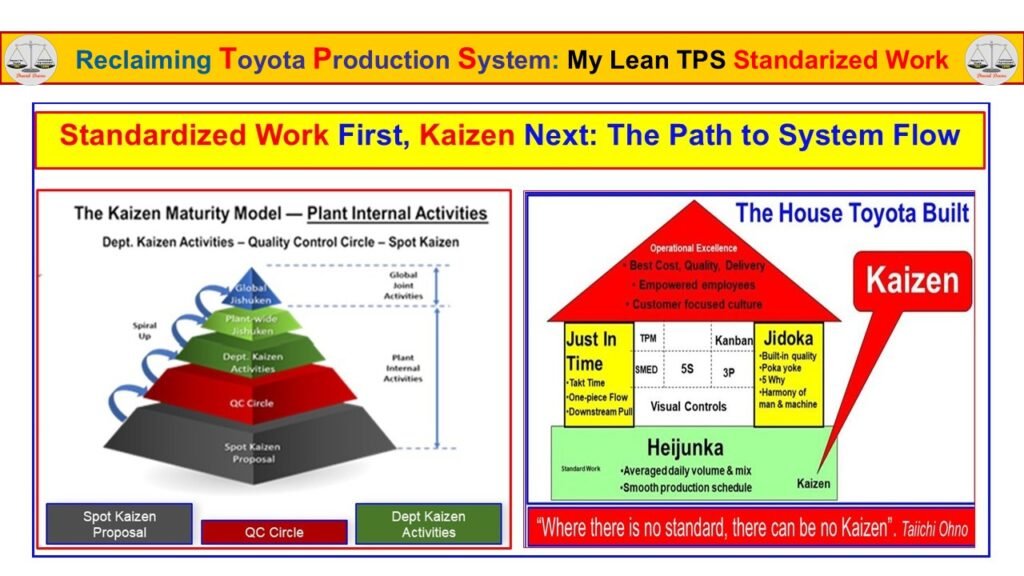

18. Standardized Work First, Kaizen Next: The Path to System Flow

Why Lean TPS requires Standardized Work to exist before improvement activity can safely scale

Lean TPS does not treat kaizen as a starting point. Improvement begins only after the current condition is defined, stabilized, and made visible through Standardized Work. This section explains why Lean TPS places Standardized Work at the foundation of all improvement activity and how disciplined standards allow learning to scale from local problem solving to system-wide improvement without introducing instability or Quality risk.

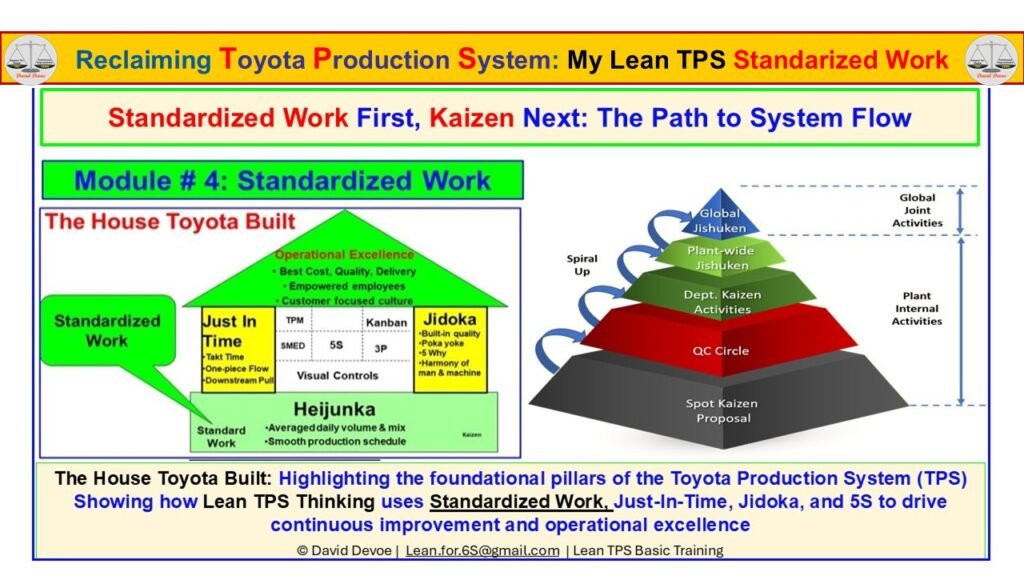

Figure 18. Standardized Work as the Foundation for Kaizen and System Flow

Standardized Work anchors Just-In-Time, Jidoka, and Heijunka, enabling kaizen to progress from local actions to plant-wide and global learning.

From defined standards to structured improvement

In Lean TPS, Standardized Work defines the normal condition for how work is performed. This includes sequence, timing, staffing, and Quality checks. By defining normal, the system creates a fixed reference that makes abnormal conditions visible immediately. Without this reference, variation is absorbed through individual judgment, experience, or effort, and improvement becomes subjective rather than verifiable.

Kaizen is applied only after this stability exists. At Toyota, kaizen is understood as small, incremental improvement at the point of work. It begins with spot kaizen, where individuals correct problems as they are encountered. These actions are local, contained, and limited in scope. Once a change is made, responsibility shifts to leadership. Leaders must confirm that the change protects Quality, verify that the result is stable, and ensure Standardized Work is updated so the improvement becomes the new normal.

As learning accumulates, improvement expands into Quality Control Circles. QCC activity is group-based and area-focused. Its purpose is not idea generation, but Quality control. Teams measure performance against a known standard, detect abnormality, and contain risk within the area. Because QCC operates at the group level, issues can be escalated area-to-area rather than person-to-person, reinforcing Jidoka and preserving respect for people.

Beyond QCC, kaizen may expand to the department level. At this stage, interfaces between processes are addressed and flow is improved across a wider scope. These improvements remain incremental and are validated against Standardized Work to ensure stability is not lost. Lean TPS deliberately limits how far kaizen can scale without stronger leadership involvement. Uncontrolled expansion increases variation faster than learning.

When improvement requires structural change, Lean TPS shifts from kaizen to jishuken. Jishuken is not an improvement event. It is a leadership development mechanism used to study systems, redesign work, and build the capability to manage complexity. Internal jishuken must occur before learning is shared externally. Only proven, stabilized learning is transferred through global jishuken and yokoten, ensuring wisdom spreads without replicating failure.

This progression is intentional. Each level increases scope, risk, and leadership accountability. The spiral upward reflects how learning matures over time, moving from local correction to system capability. Standardized Work is the gate at every stage. It ensures that improvement is verified, sustained, and transferable.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, this discipline becomes essential. Humans naturally compensate for variation. Humanoids do not. Improvement activity that is not anchored in Standardized Work creates misalignment between human behavior and machine execution. By placing Standardized Work first, Lean TPS provides a shared reference that allows humans and humanoids to learn, improve, and scale together without increasing safety or Quality risk.

Lean TPS does not restrict improvement. It protects it. Standardized Work makes kaizen safe, jishuken effective, and yokoten meaningful by ensuring that learning strengthens the system rather than destabilizing it.

19. Jishuken and the A3: Structured Learning Through Standardized Problem Solving

Why Lean TPS uses the A3 to convert improvement activity into shared system knowledge

Lean TPS treats improvement as a disciplined learning process, not a collection of isolated fixes. Jishuken provides the structure for developing capability by forcing teams to study the current condition, identify causes, and verify countermeasures against Standardized Work. This section explains how the A3 functions as the backbone of Jishuken and why Lean TPS relies on it to convert local improvement into repeatable system learning that protects Quality.

Figure 19. Jishuken A3 Linking Current Condition, Target, and System Strategy

The A3 integrates background, current condition, analysis, targets, and strategy to ensure improvement is grounded in reality and aligned to system flow.

Learning before fixing

In Lean TPS, the purpose of Jishuken is not speed of correction. The purpose is depth of understanding and capability building. The A3 forces this discipline by requiring the team to document the background and the current condition in a way that can be challenged, verified, and taught. Demand patterns, performance variation, option content, work balance, and flow constraints are made visible so the problem is framed accurately. When the current condition is unclear, countermeasures become guesswork and Quality risk increases.

Breaking down the problem follows the same logic. The A3 requires the team to separate symptoms from causes and to evaluate options against flow, takt, and stability rather than convenience. This protects the system from local optimization. It also prevents changes that improve one station while creating shortages, overload, or Quality escapes downstream.

Targets on a Lean TPS A3 are defined as capability conditions, not output wishes. Standardized cycle time stability, balanced work content, reduced variation, and stronger Quality containment become the measures of success. Strategy then connects countermeasures directly to those capability targets. The test is simple: does the countermeasure strengthen Standardized Work and make Quality easier to protect, or does it bypass the standard and create a new form of variation.

The A3 also creates alignment and transferability. Because the full story is visible on one page, leaders and teams share the same logic, the same data, and the same expectations. This is the foundation for yokoten. Learning can be transferred across lines, departments, and plants because the thinking is explicit, the assumptions are visible, and the results can be compared to a defined standard.

In Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid production, this discipline becomes even more important. Complex systems amplify the cost of misunderstanding. Humans compensate when conditions drift. Humanoids execute what they are taught. The A3 prevents improvement from becoming uncontrolled experimentation by forcing the team to study interactions between people, machines, information flow, and Quality checks before the new method is standardized.

Jishuken supported by the A3 does not accelerate change by skipping steps. It accelerates learning by preventing rework, misalignment, and repeated failure. By grounding improvement in Standardized Work and verified understanding, Lean TPS converts problem solving into lasting system capability that protects Quality.

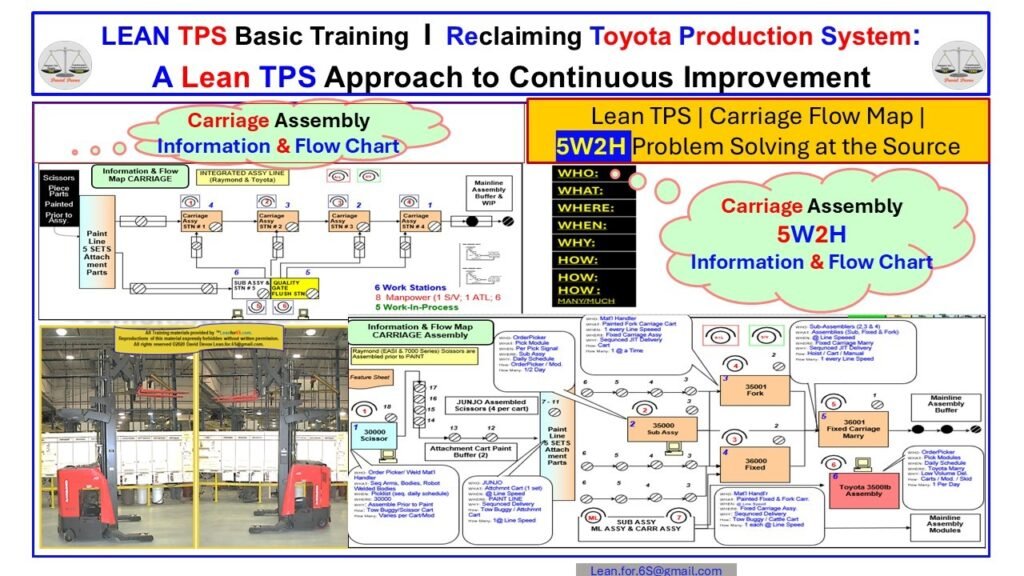

20. Information and Flow Maps Reveal the True Current Condition

Why Lean TPS uses Information and Flow Maps to make system reality visible before improvement

Lean TPS requires a clear and shared understanding of how work, information, and material actually flow through the system. Without this shared reality, improvement efforts drift toward assumptions, opinions, or isolated optimization. Information and Flow Maps are used to expose the true current condition at the line level so that Quality can be protected before change is introduced.

These maps make visible what is normally hidden. Sequence, work in process, manpower allocation, inspection points, and control logic are documented as they exist today. This allows operators, leaders, and support functions to see the same system and speak from the same facts. In Lean TPS, improvement does not begin with solutions. It begins with understanding the system as it truly operates.

Information and Flow Maps are deliberately practical. They are not analytical artifacts created for presentations. They are designed to be printed, carried to the floor, and used while walking the process. Their purpose is to make instability visible so that Quality risks can be addressed at the system level rather than absorbed through compensation.

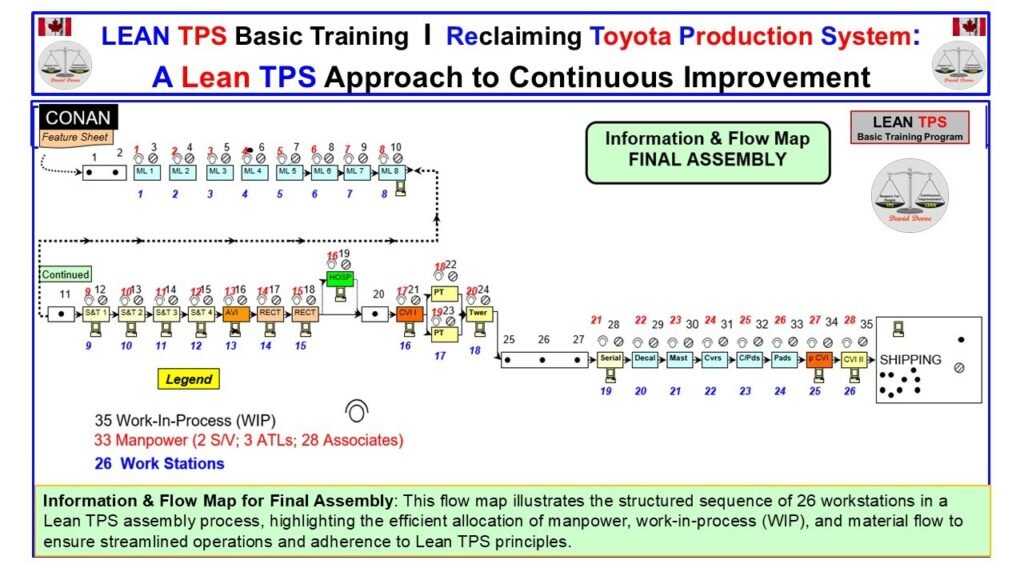

Figure 20. Information and Flow Map for Final Assembly

The Information and Flow Map visualizes workstation sequence, material flow, WIP levels, and manpower distribution to expose the true operating condition of the assembly system.

Seeing flow, readiness, and Quality control as a system

An Information and Flow Map is not a layout drawing or a planning tool. It is a factual representation of how the system is operating today. In the Final Assembly example, the map shows the full progression from assembly through inspection, rectification, finishing, and final certification. This progression makes clear where functional readiness is created, where Quality is verified, and where constraints shape system behavior.

The eight Mainline assembly stations complete post marriage assembly. After marriage, the unit can self move but cannot operate any functions until Mainline assembly is complete. Each Mainline station performs specific adjustment and component installation activities that collectively establish functional readiness. This clarity prevents premature inspection and ensures that Quality checks occur only after the system has completed its designed work.

Following Mainline assembly, four Set Up and Test stations prepare the unit for Assembled Vehicle Inspection. AVI is a production owned verification that confirms assembly completeness and functional readiness before paint. This timing is critical. Once paint and covers are applied, many defects can no longer be inspected or corrected. The map makes this Quality logic explicit by showing inspection in relation to irreversible process steps.

Rectification stations are shown as designed expert nodes, not as waste. Every unit requires some level of adjustment. Some adjustments are part of the normal process design, while others address accumulated Quality issues that must be resolved before finishing. These stations exist to protect downstream Quality. In contrast, the Hospital is an offline area reserved for true defects that should not have been present. Its WIP reflects current condition reality during change, not a desired state. Reducing Hospital WIP is a Quality objective, not a productivity exercise.

The map also exposes physical constraints. Paint touch up and the tower booth require man up access and form a hard throughput limitation. Downstream processes such as decals, covers, pads, and mast assemblies further restrict inspection access. Post cover inspection focuses on reviewing prior findings and confirming condition before final certification for shipping. By making these relationships visible, the map prevents defects from being buried and protects Quality at each irreversible step.

In a Lean TPS mixed model human humanoid environment, Information and Flow Maps become even more critical. Automated systems execute exactly as defined, while humans adapt in real time. Without a clearly defined current condition, misalignment between people, machines, and material increases rapidly. These maps provide the foundation for deciding where humanoids can add value, such as inspection, and where human skill and dexterity remain essential, such as fine adjustment, paint touch up, and cover installation.

Information and Flow Maps do not prescribe solutions. They establish reality. By making flow, manpower, WIP, inspection logic, and constraints visible, Lean TPS ensures that improvement starts from facts, protects Quality, and strengthens the system rather than optimizing isolated points.

21. Using 5W2H to Anchor Problem Solving at the Source

Why Lean TPS uses 5W2H to connect Information and Flow Maps to disciplined problem solving

Information and Flow Maps show what is happening in the system. At a change point, that visibility alone is not enough. Lean TPS uses 5W2H to understand why conditions are changing, what is breaking down, and how the system must respond to protect Quality during transition.

Toyota assumes that at any meaningful change point, not everything can be predicted or planned. New interactions, new failure modes, and new gaps will surface only once the system is running. 5W2H provides a disciplined way to capture these realities as they emerge and to prevent people from compensating silently for system weakness.

In Lean TPS, 5W2H is not a classroom tool or a template exercise. It is applied directly to the Information and Flow Map so that problem solving remains anchored in the real flow of work. This ensures that countermeasures strengthen the system rather than optimizing isolated points during periods of instability.

Figure 21. Carriage Assembly Information and Flow Chart with 5W2H Overlay

The Information and Flow Chart integrates 5W2H questions directly into the flow map so problems are analyzed at the point where work, material, and information interact.

Managing change points through flow based problem solving