How Kaizen Became a Portable Method by Removing the Governance That Once Bounded It

Kaizen(post-1980s) Did Not Transfer with Toyota Production System Governance

Kaizen entered Western management vocabulary in the mid-1980s as a named and teachable improvement practice. Its most visible introduction came through Masaaki Imai’s work, where Kaizen was formalized as a transferable method that organizations could adopt independent of Toyota. What did not transfer with that formalization was the governance structure that originally constrained, verified, and limited Kaizen’s role inside the Toyota Production System.

Inside the Toyota Production System, Kaizen was never autonomous. It operated as a bounded mechanism downstream of Standardized Work and under leadership governance. Its purpose was to refine execution, stabilize processes, and expose abnormalities that exceeded local authority. Kaizen did not determine priorities, redesign systems, or compel leadership response. Those responsibilities were intentionally located elsewhere in the system.

When Kaizen was abstracted for external use, that boundary was removed. The method traveled. The governance did not. As a result, Kaizen began operating as a standalone improvement activity rather than as a subordinate mechanism inside a governed production and management system. This was not a misuse of Kaizen. It was a structural change driven by the requirement for portability.

From that point forward, improvement activity could exist without enforced escalation, leadership study, or system-level verification. Kaizen became something teams performed rather than something that signaled when governance was required. This shift marks the starting point for understanding how Kaizen(post-1980s) separated from its original role and why its outcomes changed as a result.

Kaizen Inside the Toyota Production System Was Never Autonomous

Inside the Toyota Production System, Kaizen was never designed to operate as an independent improvement engine. It functioned as a bounded mechanism, activated only within a governed production and management system. Its purpose was narrow and precise. Kaizen refined execution against an established standard and exposed gaps that exceeded local authority. It did not define direction, redesign systems, or substitute for leadership responsibility.

That boundary was enforced structurally. Kaizen operated downstream of Standardized Work, not in place of it. Without a defined normal condition, Kaizen had no reference. Improvement activity was valid only to the extent that it stabilized work, reduced variation, and reinforced the standard. Where standards were absent, unstable, or contested, the activity was not Kaizen. It was system design work and required leadership intervention.

This distinction mattered because Kaizen did not carry governance. It could not compel stop logic, enforce Quality decisions, or obligate leadership response. Those responsibilities were intentionally located elsewhere in the system. Kaizen generated learning and surfaced problems. It did not determine which problems mattered, how far change could go, or when local improvement had reached its limit.

For that reason, Kaizen inside the Toyota Production System was never expected to scale itself. When problems exceeded local scope, they were not addressed through larger or more frequent Kaizen activity. They were escalated into leadership study and verification. Authority shifted upward because responsibility did. Local teams strengthened execution. Leaders examined system design, capacity decisions, and structural constraints.

This separation preserved system integrity. Kaizen remained disciplined because it was constrained. It remained effective because it was subordinate. Improvement activity did not replace governance. It signaled when governance was required.

When Kaizen is evaluated outside this structure, it appears incomplete. Inside the system, it was intentionally so.

Jishuken Provided the Governance Kaizen Did Not Carry

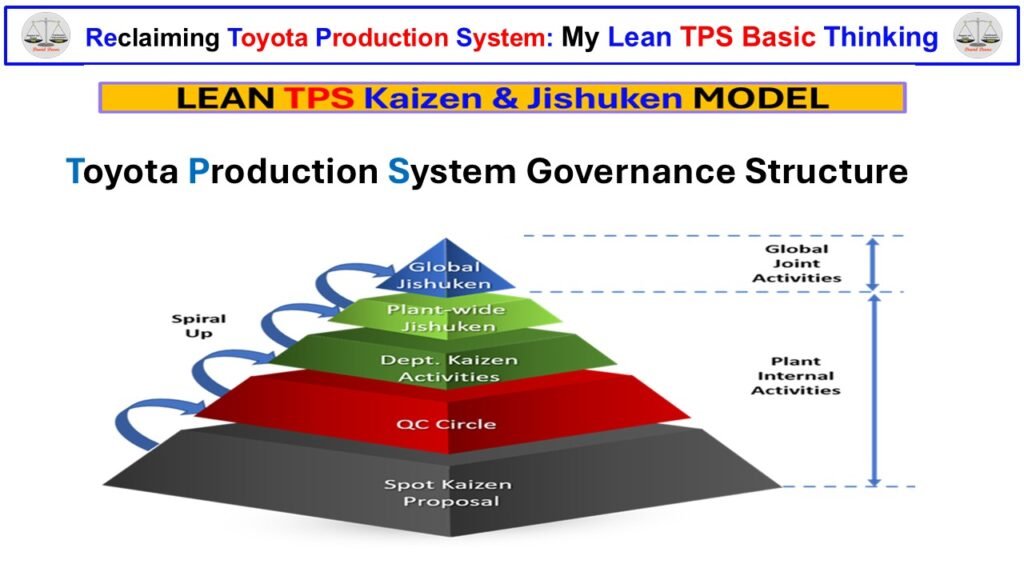

Kaizen did not govern itself inside the Toyota Production System. Governance was intentionally separated and placed within Jishuken. This separation was not incidental. It was foundational to how the system protected Quality, maintained control, and enforced leadership accountability.

Jishuken functioned as a leadership discipline, not an improvement activity. Its role was to study system behavior under real operating conditions, verify whether learning from Kaizen belonged in the system, and obligate leadership response when local improvement reached its limit. Problems elevated through Kaizen were not solved by expanding Kaizen. They were examined through structured study, comparison against standards, and verification at the leadership level. Authority moved upward because responsibility did.

This governance layer ensured that Kaizen remained bounded. Local teams focused on execution against Standardized Work. Leaders examined system design, capacity decisions, interfaces between processes, and structural constraints. Jishuken absorbed complexity that Kaizen was never intended to carry. Without this separation, improvement activity would drift toward substitution, where effort replaces design and repetition replaces learning.

Jishuken also prevented false scaling. Improvement did not spread through replication of local solutions. It spread through leadership learning. Patterns were identified across areas, conditions were compared, and decisions were made about what belonged in the system versus what remained contextual. This protected Quality by design rather than by effort.

Inside the Toyota Production System, Kaizen without Jishuken would have been dangerous. Jishuken without Kaizen would have been blind. Together, they formed a closed loop. Kaizen exposed reality at the point of work. Jishuken governed response at the system level. The system learned without losing control.

When Jishuken is removed or ignored, Kaizen inherits responsibilities it cannot fulfill. Governance collapses into activity. Leadership obligation weakens. Improvement continues, but system integrity erodes. This is not a failure of Kaizen. It is the predictable outcome of removing the structure that bounded it.

Kaizen(post-1980s) Removed the Governance Layer

Kaizen(post-1980s) emerged when Kaizen was formalized for external use and separated from the Toyota Production System that governed it. In order to travel, Kaizen was abstracted. In that abstraction, the governance layer did not transfer. Jishuken did not move with it. Leadership obligation was no longer structurally enforced.

Once separated from system governance, Kaizen changed function. It no longer operated as a bounded mechanism refining execution against an enforced standard. It began operating as a standalone improvement method. Activity replaced escalation. Effort replaced design. Improvement became something teams performed rather than something leaders were obligated to study and verify.

This shift altered responsibility. Problems that previously would have triggered leadership study remained local. System design gaps were addressed through repeated Kaizen rather than structural correction. Without Jishuken, there was no mechanism to determine when local improvement had reached its limit. Kaizen expanded upward to fill the void.

Portability required simplification. Simplification removed constraint. Constraint had been the safeguard. Kaizen(post-1980s) could now be taught, deployed, and repeated without requiring the presence of a governing production and management system. Results depended on energy, coaching, and persistence rather than enforced conditions.

This was not misuse. It was a design change. Kaizen(post-1980s) was constructed to function without governance because governance does not scale easily across organizations. What scaled was method. What did not scale was accountability for system behavior.

From that point forward, Kaizen could succeed locally while the system failed globally. Quality improvement appeared active while structural problems accumulated. Leadership involvement became optional. Kaizen survived. Governance did not.

When Kaizen Becomes the Substitute for Governance

Once Kaizen(post-1980s) operates without a governing system, it begins to absorb responsibilities it was never designed to carry. Improvement activity expands upward to compensate for the absence of leadership study and system verification. What is often described as empowerment is, in practice, substitution.

Kaizen becomes the mechanism through which organizations attempt to correct system design gaps. Capacity imbalances, unclear authority, unstable standards, and misaligned objectives are addressed through repeated local improvement rather than structural correction. The volume of Kaizen increases while the system itself remains unchanged.

This substitution creates a false signal. Activity suggests progress. Workshops suggest momentum. Metrics show short-term gains. Meanwhile, the conditions that protect Quality are no longer enforced by design. Stop logic weakens. Standardized Work becomes optional. Leadership response depends on individual judgment rather than obligation.

Without governance, escalation disappears. Problems circulate at the local level. Teams are encouraged to solve issues that exceed their authority. When improvement stalls, the response is more Kaizen. This cycle rewards effort and persistence while allowing system-level defects to persist unexamined.

The absence of Jishuken removes the mechanism that distinguishes execution problems from system problems. Everything is treated as improvable through local action. The boundary that once protected both people and Quality collapses. Responsibility diffuses. Accountability blurs.

In this environment, Kaizen does not fail. It is overused. The failure is structural. Governance has been replaced by activity. Leadership obligation has been replaced by participation. The system continues to produce results until it cannot. When it breaks, the response is more improvement rather than redesign.

Reasserting the Boundary Kaizen Requires

Kaizen does not need to be redefined, expanded, or modernized. It needs to be recontained. Inside the Toyota Production System, Kaizen functioned because its boundary was explicit. It refined execution within defined limits and signaled when those limits had been reached. Governance began where Kaizen ended.

Reasserting this boundary restores role clarity. Kaizen refines work against Standardized Work. It stabilizes processes and exposes abnormality. It does not set priorities, redesign systems, or arbitrate tradeoffs. Those responsibilities belong to leadership operating through a governed production and management structure.

Restoring governance does not diminish Kaizen. It protects it. When escalation is enforced, Kaizen no longer substitutes for leadership. When verification is required, improvement activity aligns with system intent. When accountability is structural, Quality is protected by design rather than by effort.

This boundary also restores learning. Local improvement produces insight. Leadership study determines whether that insight belongs in the system. What scales is not activity but understanding. What spreads is not solutions but conditions. This is how improvement strengthens the system without eroding control.

Kaizen(post-1980s) demonstrated that improvement activity can travel without governance. The Toyota Production System demonstrates that sustained Quality cannot. Reclaiming Kaizen does not require rejecting its external use. It requires acknowledging what was removed when it was made portable.

The boundary is not philosophical. It is operational. Kaizen operates inside a governed system or it becomes a substitute for one. When substitution occurs, improvement increases while system integrity declines. Restoring the boundary restores both.

Closing Boundary: Kaizen Cannot Govern What It Does Not Control

Kaizen was never intended to govern a production system. It was designed to operate within one. When Kaizen is separated from governance, it does not become more powerful. It becomes responsible for outcomes it cannot guarantee. Quality becomes conditional. Leadership accountability becomes discretionary. System behavior depends on effort rather than design.

The Toyota Production System prevented this outcome by design. Roles were deliberately separated. Kaizen exposed reality at the point of work. Jishuken governed response at the leadership level. Standardized Work defined normal. Stop logic protected Quality. Each element carried a specific responsibility. None substituted for another.

Kaizen(post-1980s) demonstrated that improvement activity can function without this structure. It also revealed the limit of that approach. Without governance, improvement accumulates locally while system integrity erodes globally. Results persist until leadership changes, scale increases, or operating conditions tighten. At that point, the absence of governance becomes visible.

Reclaiming Kaizen does not require abandoning its external use. It requires restoring clarity about what Kaizen can and cannot do. Improvement activity cannot replace system design. Participation cannot replace leadership obligation. Culture cannot replace enforced conditions.

The boundary is simple. When the Toyota Production System is in use, Kaizen operates within it and signals when governance is required. When governance is absent, Kaizen becomes a substitute. That substitution does not fail immediately. It fails predictably.

This distinction matters now because organizations continue to invest heavily in improvement while losing control of the systems improvement depends on. Kaizen remains active. Quality becomes fragile. The issue is not intent. It is structure.

Lean TPS: The Thinking People exists to keep that structure visible.

Close Out

This article continues the work of making system boundaries visible where they have been blurred by portability and abstraction. Kaizen remains valuable only when it operates within a governed production and management system that enforces Quality, escalation, and leadership accountability by design. When that structure is removed, improvement persists while control erodes.

Lean TPS: The Thinking People exists to document these boundary conditions as they are applied in real systems. The issues examined here are not theoretical. They are visible in daily execution, reflected in results, and predictable in their consequences when governance is absent.

Continuity With the Earlier Articles in This Series

This article extends a line of inquiry developed across earlier work on LeanTPS.ca, each examining a different pathway through which governance was separated from system behavior.

Six Sigma (post-1990s) and Lean Six Sigma (post-2010s): How Quality Governance Was Replaced examined how certification, projects, and belt hierarchies displaced management ownership of Quality, producing technically capable organizations without durable control.

https://leantps.ca/six-sigma-lean-six-sigma-quality-governance/

Why the Toyota Production System Is Being Rewritten to Fit Lean (post-1988) examined how TPS was abstracted into frameworks and interpretations once its operating conditions were removed, making outcomes dependent on intent rather than structure.

https://leantps.ca/toyota-production-system-vs-lean-post-1988/

Why Compare Industrial Engineering and the Toyota Production System: Governance Preceded Optimization examined why technical disciplines with strong analytical foundations repeatedly fail to sustain Quality without governance. It showed how Industrial Engineering and TPS share common roots in system analysis, yet diverge structurally once authority, stop logic, and leadership obligation are considered. The comparison clarified why optimization explains systems, but only governance controls behavior under pressure.

https://leantps.ca/why-compare-industrial-engineering-and-the-toyota-production-system-governance-preceded-optimization/