The Loom as a System Design Decision, Not a Historical Artifact

Jidoka design intent defines how Quality is governed by system structure rather than inspected in later or compensated for by people.

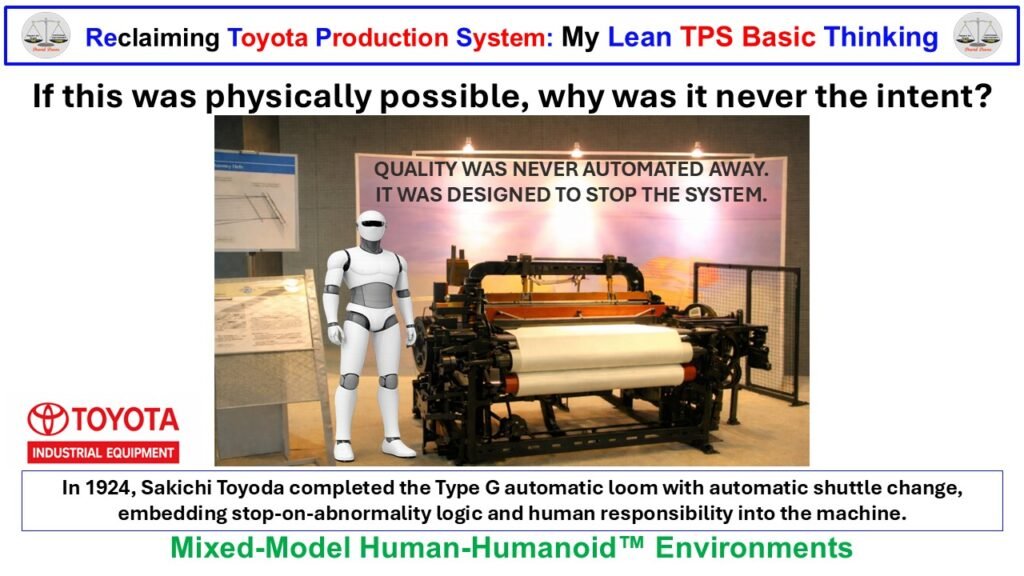

The loom in this image matters because of how it was designed more than one hundred years ago. In 1924, Sakichi Toyoda completed the Type G automatic loom, a machine that did not prioritize continuous motion or maximum output. Instead, it was deliberately designed to stop when an abnormal condition occurred.

When the thread broke or the shuttle ran empty, the loom stopped automatically. Production could not continue until the abnormal condition was corrected and the system was deliberately restarted. This behavior was not an enhancement added later, nor was it a safeguard layered on top of an otherwise autonomous machine. It was the core design decision. The loom embodied Jidoka.

Jidoka in the loom was not about automation replacing people. It was about making abnormality visible and non-ignorable. The stop was not a failure state. It was the system doing exactly what it was designed to do. By stopping, the loom prevented defects from propagating, prevented output from masking Quality problems, and forced a response before work could resume.

This distinction matters because most production systems of that era, and many today, were designed to continue operating even when conditions degraded. They relied on downstream inspection, rework, or human vigilance to protect Quality after the fact. Toyoda’s loom rejected that logic. Quality was protected at the point of occurrence by stopping the system itself.

The intelligence of the loom was therefore not speed, flexibility, or automation. It was governance. The system made a clear statement: production without Quality was unacceptable, and no amount of throughput justified continuing under abnormal conditions.

This design choice is the starting point for understanding why the loom remains relevant today. It was not built to minimize human involvement. It was built to define exactly when human involvement was required and to make that requirement unavoidable.

Human Response as a Designed System Role

Once the loom stopped, the role of the human was neither discretionary nor improvised. The system had already decided that production could not continue. What remained was a defined response to restore normal conditions and allow a deliberate restart. Human action was not an add-on to automation. It was an intentional system role.

In the Type G loom, the human response was bounded and specific. The operator did not diagnose abstract problems or make situational tradeoffs about output versus Quality. The abnormal condition was physical and visible. A thread had broken. A shuttle was empty. The required response was equally concrete: rethread, replace the shuttle, confirm normal condition, and restart. The system dictated when action was required and what constituted acceptable restoration.

This distinction matters because it separates human responsibility from human compensation. The operator was not compensating for weak design, variability, or missing standards. The operator was executing a known response inside a governed system. Judgment existed, but it operated within defined limits. There was no option to bypass the stop, delay the response, or continue production while “keeping an eye on it.”

Over time, this structure shaped behavior and learning. Operators learned what normal looked like because the system made abnormality explicit. They learned the limits of acceptable correction because restart was conditional. The system reinforced discipline not through supervision, but through design. Human capability developed in service of system stability, not in opposition to it.

This is a critical point that is often lost when Jidoka is described superficially. The value was not simply that machines could stop. The value was that stopping forced a specific human response and made that response part of the operating system. Quality was not dependent on heroics, experience, or vigilance. It was protected by the interaction between machine behavior and human responsibility.

For decades, this interaction defined how work was done. People were not asked to “make it work” under degraded conditions. They were asked to restore normal and only then resume production. That difference explains why the loom was not an early attempt at lights-out manufacturing. It was an early example of a governed system that used human capability where it added value and removed it where it introduced risk.

This design logic sets the stage for the present moment. The loom did not depend on uniquely human intuition to function. It depended on clarity: clear signals, clear stop conditions, and a clear definition of what it meant to restore Quality. That clarity is what allowed humans to perform the role reliably, and it is what now allows that role to be examined as the executor begins to change.

Human Compensation and the Illusion of System Stability

As long as humans executed the response defined by the system, stability was preserved. Over time, however, a subtle shift occurred in many production environments. Human response began to expand beyond what the system explicitly required. Compensation crept in where design clarity weakened.

When systems were incomplete, people adjusted pace, altered sequence, created informal buffers, and absorbed variation silently. They did so to keep production moving and to protect downstream customers. In the short term, this behavior appeared beneficial. Output continued. Metrics stayed green. Problems seemed contained.

In reality, this compensation masked system weakness.

Instead of abnormality forcing a stop, human effort became the buffer. Instead of clear restart conditions, judgment filled the gaps. Instead of explicit governance, experience and habit carried the system forward. Over time, the distinction between designed response and improvised adaptation blurred.

This is how instability survives inside otherwise capable organizations. When people absorb ambiguity, systems appear more robust than they actually are. Quality issues emerge later, in rework, warranty, or field failures, far from the point where they originated. Leadership intent remains implicit because escalation rarely occurs at the moment of breakdown. The system appears to function, but only because people are compensating for what design failed to make explicit.

The Toyota Production System was never intended to operate this way. Jidoka was designed to prevent exactly this form of silent degradation. The stop was meant to protect the system from continuing under abnormal conditions, not to train people to work around them. When compensation replaces stop logic, the system loses its ability to learn.

This distinction becomes critical as execution becomes more explicit. When human compensation is removed or constrained, weak design surfaces immediately. Conditions that were previously managed informally now appear as hard failures. What once looked like resilience is revealed as fragility.

This is why Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments expose problems so quickly. Humanoids do not compensate. They do not adjust pace to “help.” They do not reinterpret standards. They execute what is defined and stop when conditions are not met. In doing so, they remove the illusion of stability created by human adaptation.

What emerges is not a technology problem. It is a design truth. Systems that depended on compensation were never stable to begin with. They were stable only because people were willing and able to absorb the consequences of unclear design.

Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid Execution as a System Test

The introduction of humanoids does not change the fundamental logic established by Sakichi Toyoda’s loom. It changes the conditions under which that logic is exposed. What was once carried quietly by human adaptation is now made explicit by an executor that does not compensate.

From a physical standpoint, humanoids now possess the basic capabilities required to operate systems designed for people. They can see and detect physical states. They can manipulate objects with dexterity. They can move, position themselves, and interact with machines in predictable ways. In environments where work has been clearly defined, they can perform the same corrective actions humans have performed for decades.

This capability is not the breakthrough. The breakthrough is what it reveals.

When a humanoid encounters an abnormal condition, it does not decide whether to continue. It does not weigh output pressure against Quality risk. It does not reinterpret standards based on experience or intent. It either executes what is defined or stops. In doing so, it behaves exactly as the loom was designed to behave. It exposes whether the environment itself is executable.

This is why Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments are not a future concern. They are a present design test. Any system that relies on informal judgment, undocumented recovery logic, or silent buffering will fail immediately when execution becomes literal. What previously required coaching, reminders, or supervision now requires redesign.

The question, therefore, is not whether humanoids are capable. The question is whether the system ever was. If a process cannot be executed cleanly by an executor that follows defined conditions without compensation, then the process was never fully specified. It functioned only because humans were willing to absorb ambiguity.

In this sense, humanoids do not replace people. They remove the last remaining layer of forgiveness. They force systems to confront their own clarity. Where intent is explicit, execution remains stable. Where intent is implied, instability surfaces.

This is the same test Toyoda embedded a century ago. The loom did not ask whether the operator was skilled enough to notice a problem. It made the problem unavoidable and required a governed response. Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid execution applies that same discipline to the entire operating environment.

What is changing is not the principle. What is changing is that the system can no longer rely on human flexibility to hide design gaps.

Lean TPS as an Operating System, Not a Collection of Tools

The conditions exposed by Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid execution make one point unavoidable. Stability does not come from technology. It comes from system design. This is the original intent of the Toyota Production System.

Lean TPS was never a program for efficiency or a method for removing people. It was a way of designing work so that Quality, flow, and safety were governed explicitly rather than protected by effort, vigilance, or experience. Jidoka, Standardized Work, and visual control were not independent ideas. They were interdependent mechanisms that formed a single operating system.

Jidoka defined when work must stop and why continuing was unacceptable. Standardized Work defined what normal execution looked like and what conditions had to be met before restart. Visual control made system state obvious without explanation. Together, these elements removed ambiguity from execution and shifted responsibility from individuals to design.

This is why treating Lean TPS as a toolkit fails. When these elements are applied selectively or out of sequence, the system loses coherence. Stops occur without clear recovery logic. Standards exist without enforcement. Visuals communicate status but not action. People fill the gaps, and compensation returns.

In environments where humans adapt easily, this failure can persist for years without detection. Performance appears acceptable. Improvement activity continues. Leadership believes the system is under control. In reality, stability is being purchased through human effort rather than system clarity.

Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments remove that option. An operating system that depends on interpretation cannot survive literal execution. An operating system that relies on compensation cannot survive when compensation is no longer available.

Lean TPS, when understood as an integrated system, remains fully relevant under these conditions. It does not require new principles to accommodate new executors. It requires discipline in applying the original ones. Systems that were designed correctly continue to function. Systems that were assembled piecemeal reveal their weaknesses.

This is why the conversation must move away from humanoid capability and toward operating system integrity. The question is no longer how advanced the executor is. The question is whether the system provides clear intent, clear boundaries, and clear response logic under all conditions.

What Must Be Made Explicit Before Integration Is Possible

The progression from human execution to Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid execution forces a set of questions that cannot be deferred. These questions are not about readiness for technology. They are about readiness of the system.

What must exist for an environment to operate safely and at absolute Quality when execution becomes literal rather than adaptive? What conditions must be made explicit before integration is even considered? What logic governs response when human compensation is no longer available to absorb ambiguity?

These questions point directly back to system design. Abnormality must be detectable without interpretation. Stop conditions must be unambiguous and unavoidable. Restart criteria must be defined and enforced. Roles must be clear, and response logic must be governed rather than negotiated in the moment.

Leadership accountability changes under these conditions. When people are no longer compensating silently, responsibility for instability moves upstream. Design decisions, standards, and escalation logic become visible at the point of failure. What was previously managed through experience must now be managed through intent.

This is where many organizations struggle. They believe they are preparing for new executors when in reality they are being asked to confront incomplete system design. Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments do not introduce new complexity. They remove the tolerance for existing ambiguity.

The work, therefore, is not to teach humanoids how to behave. The work is to design environments that do not require interpretation to function. Systems must be executable as written, not improvable through effort.

These are the conditions addressed throughout my recent writing. Across the Lean TPS: The Thinking People series, I examine how 5S Thinking establishes readable environments, how Standardized Work defines normal and governs restart, and how Jishuken functions as the leadership discipline that verifies intent and response at the gemba.

Together, these elements form a single operating system for environments where execution is explicit and accountability is unavoidable. They describe what must be in place before integration is possible and why that work cannot be skipped.

Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments do not represent a departure from Lean TPS. They represent its clearest test.

Closing Perspective and Continuity of the Work

The significance of Sakichi Toyoda’s loom does not lie in its age or its mechanical ingenuity. It lies in the clarity of its intent. The loom was designed to make Quality non-negotiable, to force abnormality into the open, and to require a governed response before work could resume. That logic has not changed.

What has changed is the tolerance for ambiguity.

For decades, human adaptability allowed systems with incomplete design to function. People compensated, adjusted, and absorbed instability in ways that were rarely visible to leadership. Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid execution removes that buffer. It does not create new problems. It exposes existing ones.

In that sense, the current moment is not a technological transition. It is a design reckoning. Systems that were built with clear intent continue to operate. Systems that relied on interpretation are forced to confront their own limits. The executor is no longer the differentiator. The operating system is.

This is the continuity between past and present. Jidoka was never about automating judgment. It was about defining when judgment was required and embedding that requirement into the system itself. Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments simply extend that discipline beyond individual machines to entire operating environments.

The work ahead is therefore not speculative. It is practical and immediate. It involves making intent explicit, governing response, and designing environments that can be executed without compensation. That work sits squarely within Lean TPS as it was originally conceived.

This article, and the broader Lean TPS: The Thinking People series, exist to document and examine those conditions. Not as theory, and not as trend commentary, but as system design grounded in experience. As execution continues to change, the need for clarity does not diminish. It becomes absolute.

The loom remains relevant because the question it posed in 1924 has not changed. Can a system protect Quality by design, or does it depend on people to make up for what design leaves unfinished? Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments ensure that this question can no longer be avoided.

Where This Work Continues

The questions raised by Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments do not end with the loom, and they do not end with the introduction of new executors. They point toward a broader requirement: operating environments must be designed as complete, executable systems rather than collections of practices supported by human adaptation.

This is the focus of the ongoing work documented across Lean TPS: The Thinking People. The writing does not approach Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid execution as a technology topic. It approaches it as a system design problem rooted in the original intent of the Toyota Production System.

Across the series, three elements are treated as inseparable.

5S Thinking establishes environments that can be read without explanation. Conditions, status, and abnormalities are visible at a glance, without reliance on memory or interpretation. This is the prerequisite for any executor, human or humanoid, to act correctly.

Standardized Work defines normal execution and governs restart. It makes timing, sequence, and response explicit so that work can be performed repeatedly at Quality without reliance on compensation. When execution becomes literal, this clarity is no longer optional.

Jishuken provides the leadership discipline required to verify intent, observe execution, and govern response at the gemba. It closes the loop between design and reality and ensures that learning occurs where systems fail, not after results degrade.

Together, these elements form an operating system suited to environments where execution is explicit and accountability cannot be deferred. They describe what must be in place before integration is possible and why partial adoption is insufficient.

The introduction of humanoids does not require new principles. It requires returning to old ones with discipline. Systems that were designed with clarity continue to function. Systems that relied on flexibility are forced to change.

This work continues because the conditions it addresses are becoming unavoidable. As execution evolves, the responsibility for design becomes more visible, not less. The path forward is not speculative. It is grounded in making intent explicit and ensuring that systems can stand on their own, regardless of who or what executes the work.

Final Reflection and Invitation to Engage

The progression from Sakichi Toyoda’s loom to Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments is not a story of technological advancement. It is a story of system clarity. The loom remains relevant because it demonstrated, a century ago, that Quality cannot be inspected in later or compensated for by effort. Quality must be governed by design.

Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid execution does not introduce a new requirement. It removes the last remaining tolerance for ambiguity. Where systems are complete, execution remains stable. Where systems are incomplete, instability becomes unavoidable. The executor simply reveals what was already present in the system.

This is the central lesson that connects past and present. Jidoka, Standardized Work, visual control, and leadership governance were never about controlling people or optimizing machines. They exist to make intent explicit and to ensure that execution aligns with that intent under all operating conditions.

As environments continue to change, the relevance of this thinking increases rather than diminishes. The question organizations must answer is not whether they are ready for new executors. The question is whether their systems are clear enough to be executed without compensation.

Additional writing on Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, Jidoka, Standardized Work, and execution governance is consolidated on LeanTPS.ca. The site serves as a reference for articles, visual examples, and applied teaching material that examine how Quality, flow, and responsibility behave when ambiguity is no longer absorbed by people.

This work continues because the problem it addresses is not theoretical. It is present, visible, and increasingly difficult to avoid.