Respect for People Is Not a Value to Promote

Respect for People in Lean TPS is not a cultural value to promote, but a system outcome created through Quality-first design and disciplined improvement.

Respect for People is often described as a value or cultural principle. In many organizations, it is treated as something to be promoted through behavior, leadership messaging, or engagement initiatives. The assumption is that if people think differently or behave differently, Respect for People will follow. Lean TPS rejects that assumption.

In Lean TPS, Respect for People is not a belief to be reinforced or a behavior to be encouraged. It is a system outcome. It emerges from how work is designed, governed, and improved. When systems are well designed, people are not required to compensate for ambiguity, instability, or weak decision structures. Respect for People is visible in daily work because people can perform their jobs without constant adjustment, recovery, or defensive effort.

When systems are weak, the opposite occurs. Ambiguity migrates into daily execution. Instability becomes normal. Decisions that should have been resolved through design are pushed onto operators and frontline staff. In these conditions, Respect for People is reduced to intention rather than reality. No amount of messaging or leadership emphasis can offset the burden created by poor system design.

Lean TPS therefore treats Respect for People as a diagnostic outcome. If people are consistently compensating through extra effort, workarounds, or informal coordination, the system is failing to respect them. The issue is not attitude or engagement. It is structure. Respect for People improves only when the system is changed so people are no longer required to absorb its weaknesses.

Quality Improvement Makes Respect for People Visible

Quality improvement is the mechanism that makes Respect for People tangible in daily work. In Lean TPS, Respect for People is not inferred from intent, attitude, or leadership behavior. It is observed through the absence of forced work, recurring problems, and chronic instability. Where Quality is strong, people are not required to compensate. Where Quality is weak, compensation becomes part of the job.

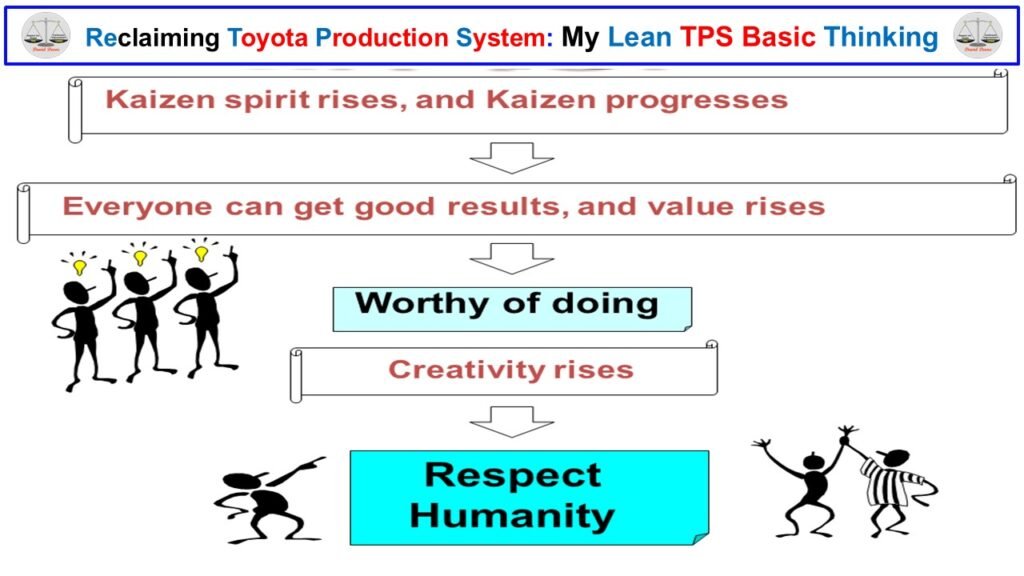

Kaizen in Lean TPS does not exist to generate ideas, encourage participation, or create engagement. It exists to remove the conditions that force people to work around defects, delays, and unclear standards. When Quality is weak, people compensate through additional checking, rework, expediting, and informal fixes. Over time, this compensation becomes normalized and invisible, even as frustration and overburden increase.

People want to contribute. In poorly designed systems, that energy is redirected away from value creation and toward recovery. Excess effort is absorbed through rework, checking, expediting, and informal coordination. Learning disappears as work becomes reactive and attention is consumed by preventing failure rather than improving the system that produces it. These outcomes are often misdiagnosed as cultural or behavioral issues. In reality, they are the predictable result of weak Quality design.

When Quality improvement is governed through Kaizen, these conditions change. Problems are surfaced rather than absorbed. Workarounds are eliminated rather than institutionalized. Standards are clarified so people no longer guess what “good” looks like, and abnormalities become visible at the point of occurrence. As forced work is removed, capacity is released and attention returns to improvement rather than survival.

Respect for People becomes visible at this point. Not as a stated value, but as a condition of work where people are no longer required to compensate for structural weakness. Quality improvement makes Respect for People observable, measurable, and sustainable in daily execution.

Removing Muda Before Adding Methods

Lean TPS addresses system weakness structurally rather than procedurally. Improvement begins with the removal of Muda before the introduction of new methods, tools, or equipment. This sequence matters because adding methods to an unstable system increases burden rather than capability. When waste is left in place, new methods amplify its effects instead of resolving them.

When waste exists in motion, flow, or decision-making, people are required to compensate. They walk more, wait more, search more, and make judgment calls that should have been resolved through system design. These compensations are often mistaken for flexibility or skill. In reality, they are signals of unresolved structural weakness.

Introducing new tools, procedures, or automation into this condition does not remove the waste. It embeds it. Complexity increases. Exceptions multiply. The system becomes more dependent on human effort to function, and responsibility for stability shifts further onto the people doing the work. Over time, this erodes both learning capacity and Respect for People.

Lean TPS therefore prioritizes clarity of work before sophistication of solutions. Motion is simplified before tasks are standardized. Flow is stabilized before capacity is increased. Decision points are clarified before responsibility is assigned. These steps reduce forced work and expose the true constraints of the system, allowing improvement to address root causes rather than symptoms.

Kaizen is applied where it reduces this burden. Improvement focuses on making work easier to perform as designed, not on adding activity or enforcing compliance. When Kaizen increases effort, complexity, or reliance on human compensation, it weakens the system rather than strengthening it.

By removing Muda first, Lean TPS creates the conditions where later improvements can be effective. Methods and equipment are introduced only after the work itself is stable, understandable, and repeatable. This sequence protects people from absorbing the consequences of poor design and preserves improvement capacity for learning rather than recovery.

Quality Is Governed, Not Improvised

In Lean TPS, Quality improvement is governed through discipline rather than improvised through individual judgment. Governance does not mean control from a distance. It means that the conditions required for Quality are clearly defined, confirmed in daily work, and deliberately improved when they no longer hold.

Quality is protected through explicit standards. Standards define the current best method for performing work under real conditions. They make expectations visible so abnormalities can be identified immediately rather than absorbed. Standards are followed as written, verified through use, and replaced deliberately when improved. They are not suggestions, documentation artifacts, or optional guidelines.

Countermeasures are evaluated for Safety and Quality before implementation. This sequencing is intentional. Improvements that compromise Safety or introduce Quality risk are not improvements, even if they appear efficient. Lean TPS treats Safety and Quality as entry conditions for change, not outcomes to be corrected later.

Without this governance, problems remain ambiguous and responsibility becomes negotiable. People compensate by making local decisions to keep work moving. Workarounds become normal. Learning slows as effort shifts from improving the system to maintaining output. Over time, Quality becomes dependent on individual effort rather than system design.

With governance in place, abnormalities surface consistently and at the point of occurrence. Problems are addressed at their source rather than passed downstream. Learning occurs where the work is performed, and improvement replaces heroics. Quality becomes predictable rather than dependent on experience, memory, or personal effort.

Governed Quality protects people from being the last line of defense. Responsibility for Quality remains with system design and leadership decisions, where it belongs. This is how Lean TPS sustains both Quality and Respect for People in daily execution.

Stability Enables Learning and Creativity

In Lean TPS, stability is the prerequisite for learning. Stability does not mean rigidity or the absence of variation. It means that work can be performed as designed, so deviations are meaningful rather than constant noise.

When Quality is unstable, people spend their time reacting. Attention is consumed by recovery, escalation, and short-term fixes. In this condition, learning is deferred because the immediate priority is maintaining output. Creativity is often demanded, but structurally blocked, because people are being forced to compensate rather than observe and improve.

As Quality stabilizes, work becomes predictable and abnormalities surface quickly. Predictability clarifies which variation matters and where attention should be directed. Problems become visible at the point of occurrence, making cause and effect easier to understand. This creates the conditions for learning where the work is actually performed.

Creativity follows this condition. It does not precede it. When people are no longer compensating for defects, delays, or unclear expectations, they have the capacity to observe the work, question assumptions, and improve methods deliberately. Creativity becomes focused on system improvement rather than survival.

In Lean TPS, stability is not the end state. It is the foundation. Learning builds on stability, and improvement builds on learning. This sequence protects people from overload and allows capability to develop over time, reinforcing both Quality and Respect for People.

Respect for People as an Outcome

In Lean TPS, Respect for People is not declared. It is demonstrated through the conditions under which people work. When systems are designed so individuals are not required to compensate for ambiguity, instability, or poor decisions made upstream, Respect for People becomes visible in daily execution.

This outcome is observable. People are not forced to rely on memory, experience, or heroics to maintain Quality. Judgment is applied where it adds value, not where it fills gaps left by weak design. Effort shifts away from recovery and toward improvement. Learning time reappears because work is no longer dominated by reaction.

When Respect for People is treated as a value to promote, attention is directed toward behavior. When it is treated as an outcome, attention is directed toward system design. Lean TPS makes this distinction explicit. If people are consistently compensating, the system is not respecting them, regardless of intent.

Respect for People improves as Quality improves. As work stabilizes, problems surface earlier, responsibility becomes clearer, and improvement replaces workaround. People are protected from absorbing the consequences of decisions they did not make and conditions they do not control.

This is why Respect for People cannot be separated from Quality, standardization, and disciplined improvement. It emerges when systems are designed to make good work possible and poor work visible. In Lean TPS, Respect for People is not a principle to be taught. It is the result of operating the system correctly.

Kaizen as the Mechanism That Makes It Operational

In Lean TPS, Kaizen is the mechanism that makes Quality and Respect for People operational in daily work. It is not an activity program, a suggestion system, or a participation exercise. Kaizen exists to improve the system so people are no longer required to compensate for poor design, unclear decisions, or unstable conditions.

Kaizen begins from actual conditions. Problems are identified where the work is performed, not inferred from metrics, dashboards, or reports. Improvement focuses on the work itself: the sequence of tasks, the flow of material and information, and the decisions embedded in the process. The objective is not to optimize effort, but to remove the reasons effort is required in the first place.

Quality improvement through Kaizen follows a deliberate sequence. Waste in motion, waiting, and decision-making is addressed before changes to equipment or automation are considered. This sequencing prevents improvement from embedding existing problems into more complex systems. Kaizen that adds tools without removing Muda increases burden and shifts risk onto people rather than reducing it.

Effective Kaizen replaces the current method rather than creating exceptions. When an improvement is confirmed, it becomes the new standard. This preserves learning, prevents drift, and ensures that improvement accumulates rather than fragments. Kaizen that remains optional or informal does not strengthen the system. It weakens it by allowing multiple methods to coexist without accountability.

Through Kaizen, Quality becomes stable and predictable. As instability is removed, work becomes easier to perform as designed. Abnormalities surface quickly, learning occurs at the source, and improvement becomes part of daily execution. Respect for People is sustained because people are no longer required to absorb defects, delays, or unclear expectations.

In Lean TPS, Kaizen is not separate from Quality or Respect for People. It is the disciplined mechanism that connects system design to daily execution and ensures that improvement reduces burden rather than redistributing it.

Closing

Respect for People in Lean TPS is not achieved through intention, messaging, or cultural programs. It is sustained through system design that protects people from being required to compensate for weak Quality, unclear standards, or unstable work.

Quality-first design, disciplined Kaizen, and governed standardization form a single system. When that system is operated correctly, work becomes predictable, problems surface early, and learning occurs where the work is performed. Creativity follows stability, not exhortation. Respect for People becomes visible in daily work because people are no longer carrying the burden of system failure.

Lean TPS represents applied work operating these principles beyond Toyota. The focus is not interpretation or adoption of tools, but the operation of systems that make Quality, learning, and human capability inseparable. As execution environments evolve, including Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid systems, the same logic applies. Human capability must be protected through design, not expectation.

My work, including ongoing writing on Mixed-Model Human–Humanoid environments, is published here.

For continued examination of system design, Quality, and leadership accountability, follow Lean TPS: The Thinking People.

If this perspective reflects conditions in your environment, comment to share your view, like, and share.