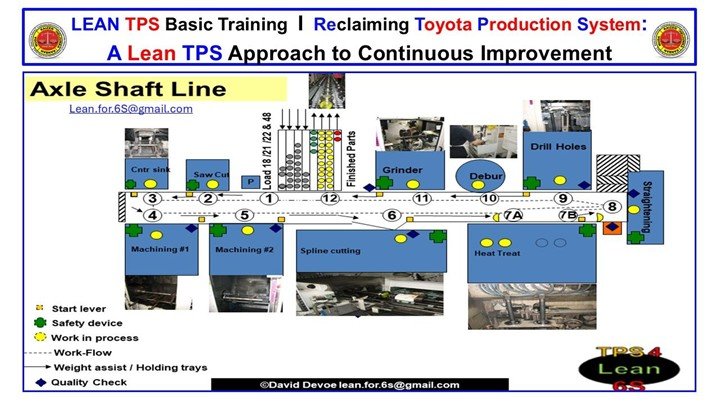

Axle shaft cell showing defined standard in-process stock points that protect flow and Quality across machining, drilling, spline cutting, heat treat, and straightening.

Capacity Planning as a Quality and Flow Problem

In-process stock capacity planning is the foundation of executable capacity inside the Toyota Production System.

Capacity planning inside the Lean TPS System does not begin with machines. It begins with Quality and flow.

Most production systems treat capacity as a numerical exercise. Available time is divided by required output, machine utilization is calculated, and work is loaded accordingly. When problems appear, additional buffer, expediting, or overtime is introduced to recover output. In this approach, Quality is inspected after the fact and instability is absorbed by people.

Standardized Work rejects this logic. In a Lean TPS system, capacity is only meaningful if it can be executed repeatedly at the required Quality level without interruption. If flow is unstable, capacity figures are theoretical. If Quality is not built into the work, output is false capacity that will later be consumed by rework, scrap, or field failure.

For this reason, capacity planning is governed by Standardized Work, not by averages or utilization targets.

Standardized Work establishes three non-negotiable conditions.

- Takt time defines the required pace of production based on customer demand.

- Work sequence defines the only acceptable order in which tasks and machine interactions occur.

- Standard in-process stock defines the minimum quantity of parts required between processes so that work can proceed continuously in that sequence.

These three elements are not documentation. They are system controls.

Takt time is not a scheduling number. It is a design constraint. It determines how machines are selected, how work is divided, how operators are assigned, and where in-process stock must exist. Any machine that cannot repeatedly complete its work within takt time at the required Quality level is not suitable for the system without additional design action.

Work sequence is not a suggestion. It is the only path through the system that preserves Quality and flow. Deviating from sequence creates hidden waiting, unevenness, and overburden that invalidate capacity assumptions.

Standard in-process stock is not inventory. It is the minimum operational condition required to prevent starving and blocking when machines with different physical behaviors must operate together. It exists because time variability is real and cannot be averaged away. When in-process stock is above the standard, abnormalities are delayed. When it is below the standard, flow breaks immediately. Both conditions are unacceptable.

Capacity planning inside Standardized Work therefore proceeds from a different question.

The question is not how much output a machine can theoretically produce. The question is whether the entire system can repeatedly meet takt time with stable flow and built-in Quality using defined work sequences and minimum in-process stock.

This article uses a real axle shaft production cell to make that logic visible. The cell was designed for human operators long before humanoids were considered. It uses specialized machines dedicated to single operations. It relies on explicit work sequence, defined standard in-process stock, and human judgment embedded inside Standardized Work to protect Quality.

Only after this system is fully understood does it become possible to see why it can be operated by general purpose humanoids with very little change.

Before any discussion of humanoids, autonomation, automation, or future systems, the capacity logic of the human designed cell must be clear. Everything that follows depends on it.

The Axle Shaft Cell as a Standardized Work System

The axle shaft cell used in this article is not presented as an optimized showcase or a theoretical model. It is a real production system designed to produce multiple axle shaft variants with consistent Quality, predictable capacity, and stable flow.

The product family includes axle shafts of different lengths and specifications. Mixed-model production occurs at the part level, not through multipurpose machines. Each machine in the line is designed to perform a narrow and well defined operation with tight operating parameters. This design choice is deliberate. Specialization improves repeatability, reduces adjustment range, and raises inherent Quality capability.

The line consists of sequential operations that include cut to length, centering, multiple machining stages, spline cutting, heat treatment, straightening, drilling, deburring, grinding, and final disposition. Each operation has distinct physical behavior. Some are dominated by automatic cycle time, others by manual work and judgment. Heat treatment introduces batch and thermal constraints that cannot be synchronized directly with machining cycles.

Because of these differences, the line is not balanced by forcing identical cycle times. Instead, it is stabilized through Standardized Work.

The work sequence defines a single correct path through the system. Parts move forward without backtracking or optional routing. Operators interact with machines in a fixed order that preserves rhythm and minimizes waiting. This sequence was established by studying motion, machine behavior, and Quality risk, not by spreadsheet balancing.

Standard in-process stock is placed at specific points in the line where timing behavior differs between adjacent processes. These locations are visible and standardized. They are not evenly spaced, and they are not negotiable. Each stock point exists to absorb known physical variation without allowing excess accumulation.

The presence of standard in-process stock allows each process to operate continuously without starving downstream operations or blocking upstream ones. More importantly, it makes abnormalities immediately visible. When stock exceeds the standard, a problem has occurred upstream. When stock falls below the standard, a problem has occurred downstream. Operators do not need judgment to detect this. The system makes it obvious.

Mixed-model execution is supported through simple but robust controls. Axle shaft blanks are color coded to identify length and specification. This visual distinction is part of the Standardized Work. It ensures correct routing, correct machine setup selection, and correct sequence execution without relying on memory or interpretation. The color does not add flexibility. It enforces correctness.

The straightening, drilling, grinding, and finishing operations rely on human capability that is often described as tacit or soft skill. In reality, these actions are bounded by Standardized Work. Operators learn what acceptable distortion looks like, how much correction is permitted, and when a part must be stopped. These judgments are not arbitrary. They are learned through repeated exposure to a stable system with clear Quality limits.

This axle shaft cell demonstrates a critical principle of capacity planning inside Lean TPS. Stability does not come from making machines flexible. It comes from making the system explicit.

Every element required to execute capacity is visible in the cell. Work sequence is fixed. In-process stock is defined. Machine behavior is understood. Quality limits are clear. Human judgment operates inside boundaries, not in place of design.

Only a system built this way can be analyzed meaningfully for capacity. Only a system built this way can later be executed by non-human operators without redesign.

In-Process Stock as a Capacity Design Variable

Standardized Work treats in-process stock differently. In-process stock in the axle shaft cell is not an outcome of poor balance. It is a designed condition that makes capacity executable.

In many production systems, work-in-process appears as a side effect. Parts accumulate because machines are mismatched, schedules change, or problems are hidden. That form of inventory has no standard. It grows and shrinks without meaning, and it obscures the true capacity of the system.

Standard in-process stock defines the minimum quantity of parts required between processes so that work can proceed continuously in the defined sequence at takt. It exists because physical processes do not behave identically, even when they are well designed. Automatic machines, manual operations, and thermal processes each introduce different timing characteristics that cannot be eliminated through averaging or planning.

In the axle shaft cell, machining operations, spline cutting, heat treatment, straightening, and finishing do not share the same completion behavior. Heat treatment operates on alternating cycles. Straightening is manual and dependent on part condition. Drilling and grinding have tight Quality tolerances that prevent rushing. These differences are inherent. They are not waste to be eliminated.

Standard in-process stock absorbs these known differences without allowing instability to propagate through the system.

Each stock location in the line corresponds to a specific timing mismatch between adjacent processes. The quantity at each point is calculated, not estimated. It represents the smallest number of parts that allows upstream and downstream operations to continue working in sequence without waiting, blocking, or improvising.

This is why the stock locations are uneven and the quantities are small. The system is not padded for safety. It is tuned for visibility.

When in-process stock exceeds the standard, it is an abnormal condition. It means a process upstream is producing without being consumed or a downstream process is unable to perform its work. Excess stock delays problem recognition and creates the illusion of capacity.

When in-process stock falls below the standard, it is also an abnormal condition. Flow stops immediately. This is intentional. The system refuses to operate under unstable conditions because doing so would force operators to compensate and hide problems.

From a capacity perspective, this behavior is critical.

Capacity is not the maximum number of parts a machine can produce in isolation. Capacity is the ability of the entire system to repeatedly meet takt with built-in Quality. Standard in-process stock is what allows that to happen when machines with different physical behaviors must work together.

In the axle shaft cell, the total standard in-process stock across the system is small, but it is sufficient to stabilize flow across all operations. This stock does not increase output. It makes output reliable. It ensures that capacity calculations based on machine completion times can actually be executed on the floor.

Without standard in-process stock, capacity planning collapses into firefighting. With it, capacity becomes a property of the system rather than the heroics of individuals.

This is why in-process stock must be designed at the same time as work sequence and machine selection. It is not something to be added later. It is a core variable in capacity design.

How Machine Capacity Is Calculated Using Standardized Work

Capacity planning in the axle shaft cell does not begin by loading machines to their limits or maximizing utilization. It begins by designing a system that can execute the required output repeatedly, at Quality, without interruption.

This distinction matters. A machine that can theoretically produce fast but cannot do so reliably within the system does not contribute real capacity.

Takt Time as the Governing Design Constraint

Capacity planning starts with takt time, calculated from customer demand and available production time. Takt time establishes the required pace of the entire system.

In Standardized Work, takt time is not a scheduling target. It is a design constraint. Once established, it governs which machines are acceptable, how work is divided, how operators move, and where in-process stock must exist. Any process that cannot repeatedly meet takt at the required Quality level cannot be accepted into the system without design changes.

Takt time therefore precedes machine selection, not the other way around.

Measuring Completion Time, Not Machine Speed

Each process in the axle shaft cell is evaluated using actual completion time, not ideal cycle time, spindle time, or nameplate speed.

Completion time includes:

- manual work time

- automatic machine cycle time

- recurring handling, positioning, and transfer elements

This matters because machines do not operate in isolation. A fast cutting cycle followed by slow loading, alignment, or inspection does not produce high capacity.

Capacity in this system is governed by completion time at the process level, not by machine speed, utilization, or theoretical output in isolation.

Identifying the Governing Constraint

Once completion times are known, each process is compared directly to takt time. The process whose completion time most closely approaches or exceeds takt becomes the governing constraint of the system.

This constraint is not a spreadsheet bottleneck. It is the physical limit that defines what the system can reliably produce.

In the axle shaft cell, machining, heat treatment, and finishing behave differently by nature. Rather than forcing artificial balance, the system is designed around the constraint and stabilized through sequence and standard in-process stock.

Designing Work Sequence Before Staffing

Operator staffing is determined after work sequence is defined.

The axle shaft cell is designed so operators move through machines in a fixed order that matches machine behavior and protects Quality. Tasks are sequenced to eliminate waiting and prevent overlapping demands.

Staffing levels are then assigned to support that sequence. This prevents the common failure mode where staffing decisions drive workarounds that invalidate capacity assumptions.

Calculating and Validating Standard In-Process Stock

With takt time, completion times, and work sequence defined, standard in-process stock can be calculated.

In-process stock is required wherever:

- completion times differ between adjacent processes

- alternating or batch behavior exists

- manual judgment introduces unavoidable timing variation

The quantity at each location is set to the minimum required to allow continuous execution of the defined sequence without starving or blocking. This stock does not protect machines. It protects flow.

Capacity is validated only by execution. If the system can run at takt, maintain standard in-process stock, and meet Quality requirements without expediting or adjustment, the capacity design is correct. If not, the design must change.

This is capacity planning as an operational condition, not a forecast.

Nagara and One-Operator Autonomation in Capacity Execution

The clearest example of this logic appears at the interface between spline cutting and heat treatment.

In this section of the line:

- The operator places an axle shaft into a weight-assist holding tray.

- Every second cycle, two axle shafts are loaded into the heat-treat machine.

This alternating pattern is not incidental. It is designed so one operator can perform concurrent actions without waiting or batching beyond the defined standard.

This is Nagara.

Nagara allows an operator to start a machine cycle as naturally as they walk to the next task. Motion and machine activation are combined so flow is continuous and rhythmical.

One-operator autonomation works here because:

- The in-process stock level is defined.

- The sequence is fixed.

- The timing relationship between machining and heat treatment is understood and protected.

Without those conditions, Nagara would collapse into overburden or hidden delay.

Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid Execution Using Human-Designed Cell

The axle shaft cell described in this article was designed entirely for human operators. Its machines are specialized. Its work sequence is fixed. Its in-process stock is defined. Its Quality controls rely on a combination of physical limits, visual signals, and human judgment learned through repetition.

Nothing in this system was created with humanoids in mind.

That fact is precisely what makes it suitable for Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid execution.

General-purpose humanoids do not succeed in environments that depend on flexibility, improvisation, or undocumented judgment. They succeed in environments where work has already been made explicit. The axle shaft cell qualifies because Standardized Work has already converted complex production into a bounded, repeatable system.

Why No Redesign Is Required

Humanoids can be integrated into this cell without rearchitecting the system because the critical elements of execution are already present:

- Machine roles are single-purpose and tightly constrained.

- Work sequence is explicit and invariant.

- In-process stock locations and quantities are fixed and visible.

- Start conditions, end conditions, and stop conditions already exist.

In other words, the system does not rely on human intuition to function. It relies on design.

This is the fundamental requirement for humanoid execution.

Mixed-Model at the Part Level

Mixed-model production in this cell is achieved at the part level, not through flexible machines. Axle shafts of different lengths and specifications move through the same sequence of specialized machines. Variation is controlled through simple, robust interfaces rather than parameter-heavy automation.

Color coding is one such interface.

For human operators, color identifies the correct routing and machine setup selection. For humanoids, color becomes a direct sensory input tied to standardized machine interaction. The humanoid does not “decide” which setting to use. The color triggers a known, validated state change.

This is not flexibility. It is correctness.

Because the machines themselves are not multipurpose, operating windows remain narrow. Tolerances remain tight. Quality capability remains high. Mixed-model execution does not dilute control.

Judgment-Based Operations Are Already Bounded

Operations such as straightening, drilling alignment, and finishing are often described as dependent on human “feel.” In reality, these tasks are governed by learned standards.

Human operators in this cell learn:

- what acceptable distortion looks like

- how much correction is permitted

- when additional correction creates risk

- when a part must be stopped

These judgments are not infinite. They operate within defined limits reinforced by repeated exposure to a stable system.

Humanoids can now perceive the same signals humans use. Vision systems can detect distortion magnitude. Force feedback can detect resistance and spring-back. Comparison to a learned standard allows adjustment within allowable bounds.

What changes is not the work. What changes is the executor.

Because the judgments were already standardized implicitly, they can now be made explicit and taught.

Learning Versus Compensating

Human operators historically compensated for design gaps. They adjusted pace when machines varied. They hid instability through effort. They protected output by bending sequence.

Humanoids do not compensate.

This is a strength, not a weakness.

In this cell, the system already forbids compensation. Deviations from standard immediately surface through in-process stock signals and flow interruption. Humanoids fit naturally into this environment because they execute exactly what the system defines.

Learning for a humanoid does not mean discovering new methods. It means internalizing existing Standardized Work, including the bounded judgments humans previously carried informally.

Safety Architecture Changes Without Reducing Safety

Because the work sequence and machine envelopes are fixed, some physical safety devices become redundant when execution is transferred to humanoids.

This does not reduce safety. It changes how safety is enforced.

Humanoids can be hard-constrained to avoid prohibited zones entirely. They do not reach into machines. They do not bypass guards. They do not improvise shortcuts. Safety becomes a function of system boundaries rather than operator vigilance.

This is only possible because Standardized Work already defines exactly where interaction is permitted and where it is not.

The Deeper Lesson

The axle shaft cell demonstrates that good Lean TPS design is inherently future-proof.

Cells built around:

- specialized machines

- explicit work sequence

- calculated in-process stock

- bounded judgment

do not depend on the humanity of the operator to function.

They depend on the clarity of the system.

Humanoids do not replace people in such systems. They expose whether the system was ever properly designed.

In this case, the answer is clear. The cell works because it was designed to make capacity, flow, Quality, and judgment explicit long before humanoids existed.

That is the real lesson of the Lean TPS Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid execution.

Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid Implications

As production environments begin to include humanoid robots alongside people, the lessons from this cell become more important, not less.

Humanoids can execute motions.

They can see, hear, feel, carry parts, start machines, and follow sequences.

What they cannot do is compensate for missing system design.

In Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid environments, undefined standard in-process stock, unclear capacity logic, and weak stop rules will surface immediately. There is no intuition to absorb instability.

This means future systems must be more explicit, not more flexible:

- In-process stock must be clearly defined.

- Capacity must be calculated from completion time.

- Flow must be protected by design.

The axle shaft cell provides a practical reference for how this is done correctly.

What This Cell Teaches About Capacity, Standardized Work, and the Future of Execution

The axle shaft cell is valuable not because it is advanced, automated, or novel. It is valuable because it is explicit.

Every element required to make capacity real is visible in the system:

- Takt time governs design rather than scheduling.

- Machine capacity is understood through completion time, not utilization.

- Work sequence is fixed and enforced.

- Standard in-process stock is calculated and minimal.

- Quality judgment is bounded and learned, not improvised.

- Mixed-model variation is controlled through simple, physical interfaces.

This is what allows the system to run predictably with human operators, and it is what allows the same system to be executed by humanoids without redesign.

The most important lesson is not that humanoids can now operate this cell. The lesson is that they can only do so because the cell was already designed correctly.

Where systems rely on human compensation, humanoids will fail.

Where systems rely on flexibility, Quality will erode.

Where systems rely on averages, capacity will remain theoretical.

This cell relies on none of those.

Instead, it demonstrates the original intent of Standardized Work: to convert complex production into a repeatable system where capacity, flow, and Quality are inseparable. In that sense, the introduction of humanoids does not change the fundamentals. It simply removes the last remaining buffer, human adaptation, and exposes the true quality of the design.

For practitioners, this has a clear implication.

If a production system cannot be executed cleanly by a humanoid following Standardized Work, it was never truly standardized to begin with.

The axle shaft cell shows what happens when it is.

Practical Takeaways: Designing Capacity-Driven Cells That Survive Operator Change

The axle shaft cell allows several practical conclusions that go beyond theory and beyond any specific executor, human or humanoid.

These conclusions are not future-oriented. They are design rules that have always existed inside Lean TPS but are now impossible to ignore.

Capacity Must Be Designed Before It Is Calculated

Capacity cannot be “found” by measuring machines after the fact. It must be designed into the cell.

In the axle shaft cell:

- Takt time was established first.

- Machines were selected for single, narrow purposes.

- Completion times were understood and accepted.

- Work sequence was fixed before staffing.

- Standard in-process stock was calculated and locked.

Only after these conditions existed did capacity become measurable.

Any attempt to calculate capacity without these steps will produce numbers that cannot be executed.

Specialized Machines Enable Mixed-Model Stability

Mixed-model production in this cell does not rely on flexible or multipurpose equipment. It relies on specialization.

Each machine performs one operation extremely well. This allows:

- tighter operating parameters

- higher inherent Quality

- predictable completion times

- easier abnormality detection

Mixed-model variation is absorbed by sequence, stock, and simple interfaces such as color coding, not by reprogramming machines.

This design choice is what makes both human and humanoid execution feasible.

Standard In-Process Stock Is a Design Commitment

SWIP is often treated as a tolerance. In this cell, it is a commitment.

Once set:

- it defines the operating envelope

- it enforces discipline

- it prevents silent degradation of flow

The moment SWIP is violated, the system signals that capacity is no longer valid.

This is why SWIP must be owned by leadership, not adjusted on the floor.

Judgment Must Be Bounded or It Will Be Lost

Operations such as straightening, drilling alignment, and finishing rely on judgment. That judgment only survives if it is bounded by Standardized Work.

In this cell:

- acceptable ranges exist

- stop conditions are known

- escalation is defined

Humanoids do not remove judgment from the system. They force judgment to be made explicit.

Systems that rely on informal human adaptation will lose that capability the moment operators change, whether to new people, contractors, or machines.

Operator Change Is the Ultimate System Test

Human to humanoid transition is not a special case. It is simply the most unforgiving form of operator change.

If a system:

- depends on experience that is not standardized

- requires flexibility to compensate for poor design

- hides problems through excess stock or effort

- it will fail under any operator change.

The axle shaft cell passes this test because it was designed to function without heroics.

Closing Observation

The future of production does not belong to the most intelligent machines. It belongs to the clearest systems.

Standardized Work was never about controlling people. It was about making systems explicit enough that any capable executor could produce Quality at takt.

Humanoids simply make that truth visible.

The axle shaft cell shows that when capacity planning, flow design, and Quality are treated as one problem, the executor becomes secondary. The system carries the intelligence.

That is the real continuity between past TPS practice and future Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid execution.Top of Form

Closing Reference

Additional writing on Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid execution is consolidated on LeanTPS.ca as part of the Lean TPS system architecture.

Three dedicated reference pages expand this logic across:

• Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid 5S Thinking

• Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid Standardized Work

• Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid Leadership

Together, these pages develop Mixed-Model Human-Humanoid execution as a Quality, flow, and capacity design problem, not a technology discussion. They show how explicit work sequence, standard in-process stock, visual control, and leadership governance determine whether humanoids can execute production reliably without redesign.

LeanTPS.ca serves as the single reference point for this system logic, integrating articles, newsletters, and long-form teaching material grounded in Toyota Production System practice.