Sustaining real Lean TPS improvement requires more than awareness. It requires disciplined action, structured problem-solving, and a commitment to continuous learning.

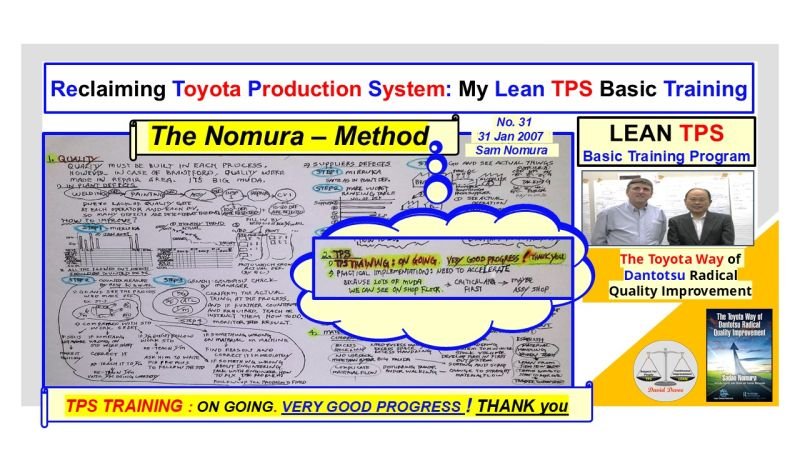

Nomura Memo No. 31, written on January 31, 2007, by Mr. Sadao Nomura, represented the first set of TPS improvement recommendations for Toyota BT Raymond in Brantford, Ontario. His guidance translated Toyota’s production philosophy into actionable direction for Brantford’s team.

The memo captured Toyota’s core improvement method—building capability through Jishuken, Genchi Genbutsu, and Kaizen. It became the foundation for transferring TPS knowledge from Toyota’s Japanese leadership to the Canadian plant, guiding its transformation from concept to daily practice.

The Jishuken Framework

The Brantford transformation was driven by Jishuken, Toyota’s self-motivated study and improvement process. This method teaches through experience, where leaders learn TPS by applying it to real problems, not by classroom explanation.

Nomura’s structured approach combined three essential elements:

- Genchi Genbutsu: Go and see the real situation.

- Standardization: Stabilize the process before improvement.

- Kaizen: Solve problems through continuous refinement.

Through Jishuken, Brantford leaders and engineers worked side by side with Toyota mentors to address waste, stabilize flow, and strengthen quality at the source.

Key Improvement Areas

Nomura identified five immediate areas for action, each tied to a core TPS principle.

1. Quality Issues

Defects were detected too late, leading to waste and costly rework.

Countermeasure: Implement Mieruka (visualization) and Genchi Genbutsu to detect abnormalities at the source. Standardize work to prevent recurrence rather than relying on inspection.

2. Supplier Defects

Variation in supplier quality disrupted production and reduced efficiency.

Countermeasure: Introduce defect ranking, root cause analysis, and corrective actions. Improve supplier accountability through standard quality metrics and feedback loops.

3. TPS Training

Training was too slow to reach key areas such as assembly and welding.

Countermeasure: Accelerate TPS Basic Training through direct coaching, on-site learning, and structured improvement cycles. Build a culture of hands-on problem-solving.

4. Material Control

Inefficient inventory handling caused excess motion and uneven flow.

Countermeasure: Implement FIFO lanes, simplify material movement, and balance work sequences. Reduce inventory to reveal problems and improve flow efficiency.

5. Future Plan for Productivity and Quality

A long-term vision was required to sustain improvement.

Countermeasure: Apply PDCA to build a roadmap for continuous improvement. Evaluate the feasibility of major process upgrades and design changes aligned with TPS standards.

The Impact of Nomura’s Guidance

Nomura Memo No. 31 was not an audit report. It was a hands-on improvement plan grounded in Toyota’s leadership principles. The memo reinforced that TPS must be practiced, not studied. Every recommendation linked action to learning.

Brantford’s progress reflected the essence of the Nomura Method—structured observation, rapid experimentation, and reflection. This process developed capability in people while strengthening the production system.

As Nomura emphasized, “TPS training is ongoing. Very good progress. Need to accelerate improvement speed.” His guidance shaped the plant’s approach to daily problem-solving and continuous improvement.

Legacy of Nomura Memo No. 31

The 2007 memo marked the beginning of Brantford’s true TPS journey. It connected Toyota BT Raymond to the broader Toyota Industries Corporation system and reinforced the expectation of Dantotsu Quality—quality better than the best.

By combining leadership learning with structured practice, the memo ensured that TPS principles became part of daily work. The Jishuken teams developed both process stability and human capability, achieving measurable improvements in quality, safety, and productivity.

Nomura’s influence remains foundational to Lean TPS training today. His method demonstrated that sustainable transformation begins not with policy but with disciplined practice, learning by doing, and leadership at the Gemba.