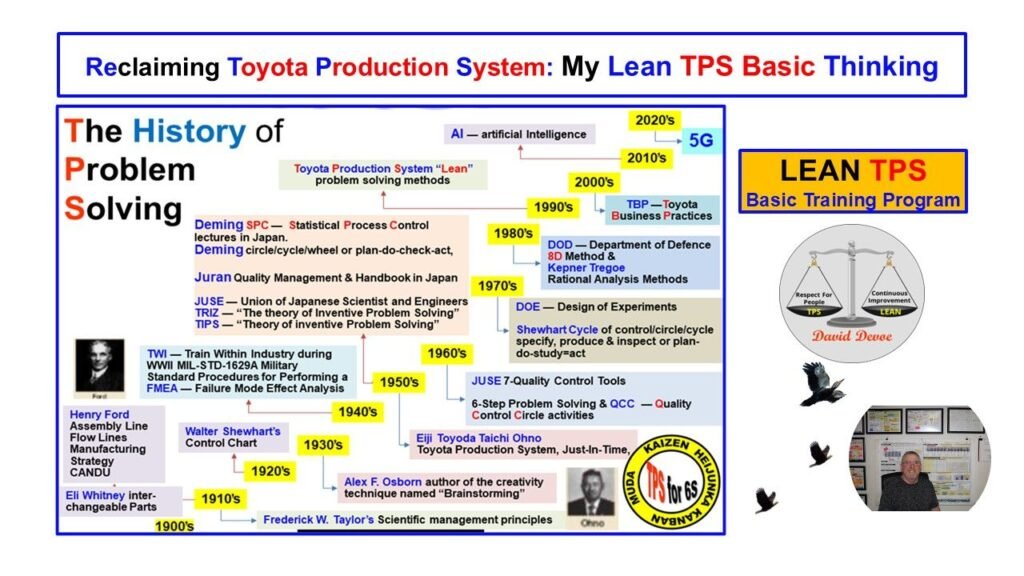

The structured approach to problem-solving used within Toyota is the result of more than a century of evolution. Each generation of thinkers and practitioners contributed new insights, tools, and methods that shaped how organizations approach improvement today. What began as efforts to control quality and stabilize production has become a complete management system for developing people and sustaining excellence.

The roots of problem-solving trace back to the early industrial pioneers. Eli Whitney introduced interchangeable parts, enabling repeatable quality. Frederick Taylor established the principles of scientific management, setting measurable standards for work. Henry Ford advanced these concepts through assembly line flow and process synchronization. Together, these pioneers created the foundation for standardization and efficiency.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Walter Shewhart introduced statistical process control, shifting problem-solving from reaction to prevention. W. Edwards Deming expanded these ideas through his cycle of Plan, Do, Check, Act, emphasizing process improvement based on facts. Joseph Juran added structure through his quality trilogy of planning, control, and improvement, giving organizations a roadmap for consistent progress.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Japan formalized these principles through the Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers (JUSE). The introduction of the 7 Quality Control Tools allowed teams to visualize problems and make decisions using data. Around the same time, Eiji Toyoda and Taiichi Ohno developed the Toyota Production System, combining standardization, flow, and problem-solving into a leadership-driven framework.

By the 1970s and 1980s, structured methods such as the Department of Defense’s 8D process and the Design of Experiments (DOE) approach expanded analytical capability. These were complemented by Toyota’s development of Total Quality Control and Jishuken, where leadership teams conducted focused studies to solve real operational problems. The result was a system that blended scientific analysis with direct observation at the Gemba.

The 1990s and 2000s introduced the Toyota Business Practices (TBP) model, a standardized approach to problem-solving using eight logical steps. TBP formalized how Toyota teaches employees to identify, analyze, and resolve issues. The same period saw the growth of Lean manufacturing in the West, translating Toyota’s principles for broader application while often losing the leadership-centered intent that defines TPS.

From 2006 to 2010, I was directly involved in Toyota Jishuken within Toyota Industries Corporation’s North American Material Handling operations. Working alongside Toyota leaders, my focus was to strengthen leadership-driven problem-solving and ensure the transfer of TPS logic into North American operations. We applied standardized methods to real problems, using data, observation, and structured reflection to align improvement with both business results and people development.

This work reinforced the central lesson of Jishuken: that the ultimate purpose of problem-solving is to develop people. Tools and methods exist to support thinking, not replace it. Each improvement cycle strengthens leadership capability, reinforces Standardized Work, and deepens understanding of the process.

Today, Toyota Jishuken continues to evolve, integrating new analytical technologies while preserving its foundation of Genchi Genbutsu, Standardized Work, and Respect for People. My experience in North America represents one link in this ongoing evolution, demonstrating how structured learning, leadership participation, and disciplined reflection sustain operational excellence.

The history of problem-solving is not a list of methods but a progression of learning. From Ford’s flow production to Ohno’s TPS and Toyota’s modern Jishuken, each stage advanced the connection between process, people, and purpose. Continuous improvement is not a single invention. It is a shared journey of discovery that continues to shape how organizations think, learn, and lead.